We talked last time about Auber‘s Gustave III (1833), a dramatic retelling of the assassination of 18th century Swedish king Gustave III at a masked ball.

Several Italian composers loved the story, and wanted to adapt it.

Bellini called it “magnificent, spectacular, historical!”; had he lived, it would have been his next project after I puritani. One Vincenzo Gabussi wrote Clemenza di Valois (1841); both he and his opera are completely forgotten. Mercadante moved the story to Scotland in his Reggente (1843).

But by far the best known version is…

UN BALLO IN MASCHERA

- Opera in 3 acts

- Composer: Giuseppe Verdi

- Libretto: Antonio Somma, after Eugène Scribe’s libretto for Auber‘s Gustave III (1833)

- First performed: Teatro Apollo, Rome, 17 February 1859

| RICCARDO, Count of Warwick, Governor of Boston [GUSTAVO, King of Sweden] | Tenor | Gaetano Fraschini |

| RENATO, Creole, his secretary and Amelia’s husband [COUNT ANCKARSTRÖM] | Baritone | Leone Giraldoni |

| AMELIA | Soprano | Eugenia Julienne-Deljean |

| ULRICA, fortuneteller [MADAME ARVIDSON] | Contralto | Zelina Sbriscia |

| OSCAR, page | Soprano | Pamela Scotti |

| SILVANO, sailor [CRISTIANO] | Bass | Stefano Santucci |

| SAMUEL and [COUNT RIBBING] | Bass | Cesare Rossi |

| TOMMASO [COUNT HORN], the Count’s enemies | Bass | Giovanni Bernardoni |

| Two Adherents | Basses | |

| A Judge | Tenor | Giuseppe Bazzoli |

| Amelia’s servant | Tenor | Luigi Fossi |

| Deputies, Officials, Sailors, Guards, Men, Women, and Girls of the People, Samuel and Tom’s Accomplices, Servants, Masked Dancers | Chorus |

SETTING: Sweden, March 1792; or Boston, the end of the 17th century.

Problems with censors forced Verdi to move the setting to that hotbed of courtly vice and dancing: 17th-century Boston. (Mainly known for burning harmless women at the stake, after the townsfolk of Salem went crazy for rye.)

These days, productions of Verdi’s opera are usually set in Sweden.

(When they’re not set on bombed-out post-industrial wastelands full of courtiers on the loo, and naked homeless people in Mickey Mouse masks, as a post-modern comment on capitalist malaise.)

We’ll stick with Sweden; it’s more sensible.

But nobody’s calling it Una vendetta in domino, which may be the coolest title for an opera ever.

ACT I

The King’s palace in Stockholm – A vast, rich waiting room

Conspirators led by Counts Ribbing and Dehorn plot to murder Gustavo. The king has worries of his own; he loves Amelia, married to Renato.

Gustavo organises a masked ball which the most beautiful women in court (including Amelia) will attend.

Renato tells Gustavo that he knows why he is unhappy – but the king is relieved when it’s only a warning of a conspiracy, not love for his friend’s wife.

Gustave learns that the fortuneteller Ulrica is under threat of exile. The young page Oscar tries to defend her, claiming that she’s not a fraud at all, but has a hotline to Satan.

– and decides to investigate for himself, in disguise.

The fortune-teller’s house

Gustavo, disguised as a sailor, arrives first at Ulrica’s. He’s amused to watch the fortuneteller wow the crowd by conjuring up Beelzebub.

Amelia arrives; she confesses she loves an important person at court, and struggles not to love him. Ulrica tells her to go at midnight, and pluck a herb from the executioner’s field. Gustavo will secretly follow her there.

The courtiers arrive. The king, still incognito, asks Ulrica to tell the sailor’s fortune.

It’s not a happy fortune: he will die, murdered by the person who first shakes his hand – Renato, arriving late.

ACT II

The executioner’s field on the outskirts of Stockholm

Midnight. Amelia arrives, frightened but determined, to get the magic herb. The vision of the king rises up before her, though.

So does the real king. He declares his love. She begs for mercy, but is tempted by her feelings. She struggles to regain her senses…

and hears at that moment someone approaching: her husband Renato! He has come to warn the king that the conspirators have followed Gustavo here, and plan to murder him. Gustavo entrusts the veiled woman to Renato’s care; he will guide her to the outskirts of Stockholm, without speaking to her. The king escapes.

The murderers arrive, and confront Renato. In the confusion, the veil falls from Amelia’s face – and everyone recognises her. Renato, thinking he understands all, arranges to meet Ribbing and De Horn the next morning – and plot Gustavo’s assassination.

ACT III

Renato’s house

Renato threatens to kill Amelia to punish her adultery. She pleads her innocence, and Renato spares her life; he will kill Gustavo instead.

De Horn and Ribbing arrive, and Renato joins their conspiracy. He is chosen by lot to kill the king. Oscar comes to invite the Ankaströms to a masked ball at the Opera that evening – for the conspirators, a perfect opportunity for murder.

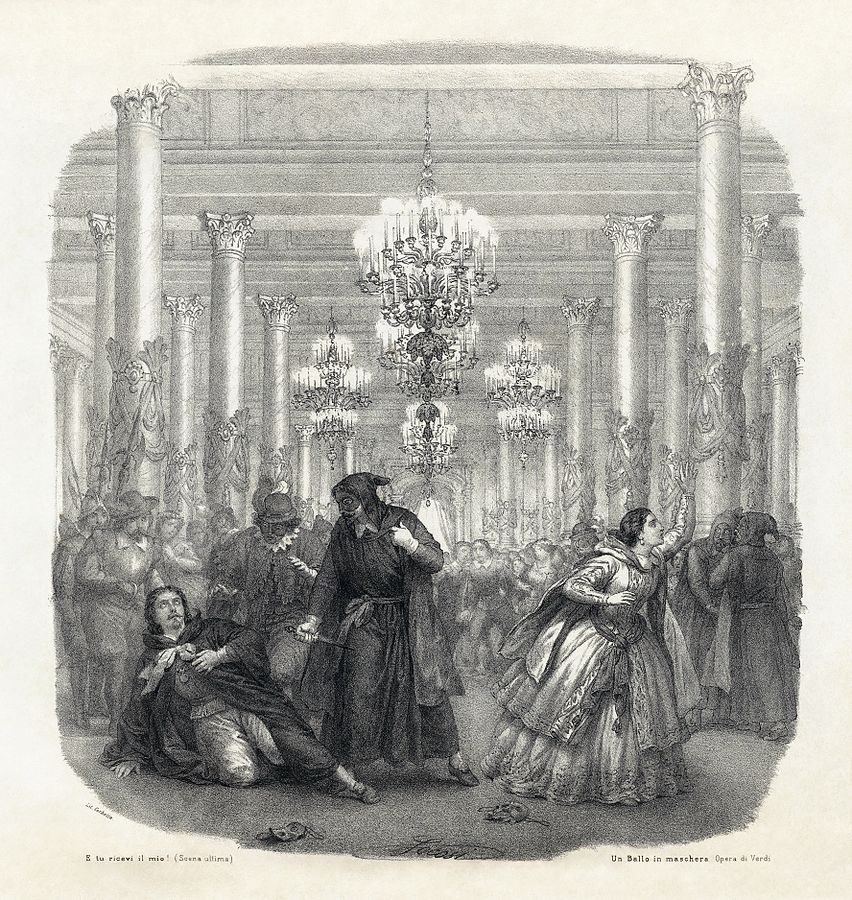

The ball

Alone, Gustavo resolves to send Amelia away. He will name Renato governor of Finland, and the couple will leave the next day.

At the height of the festivities, tragedy strikes. Amelia warns Gustavo that his life is in danger – and Renato stabs him. The dying king pardons them all.

“I’m scaling down a French drama, Gustavo III di Svezia, libretto by Scribe, performed at the Opéra twenty years ago,” Verdi wrote in 1857. “It’s vast and grandiose; it’s beautiful; but it too has conventional things in it like all operas – something I’ve always disliked and now find intolerable.”

Verdi settled on the project, intended for the Teatro San Carlo, Naples, after another failed attempt to write Il re Lear, the King Charles’ head of an opera that pursued him throughout his career.

It was, he and librettist Antonio Somma thought, a straightforward choice. The plot was a known quantity. And Verdi liked the situation of the drawing of the lots, and the mixture of tragedy and comedy that had made Rigoletto and Traviata so successful.

“That quality of brilliance and chivalry, that aura of gaiety that pervaded the whole action and which made a fine contrast, was like a light in the darkness surrounding the tragic moments.”

But the censors didn’t like it. What, kill a king? Make him a Duke, they demanded; set it in a pre-Christian time when people believed in witchcraft; and don’t set it in Sweden or Norway.

So Verdi and Somma planned to move it to 17th-century Pomerania. After the Italian revolutionary Felice Orsini tried to kill Napoleon III in January 1858, the Chief of Police ordered the libretto be completely rewritten.

I’m in a sea of troubles! It’s almost certain that the Censorship won’t allow our libretto. Why? I don’t know! How right I was to tell you that you would need to avoid any phrase or word that could be suspect. They began by taking exception to certain expressions, certain words, then from words they’ve gone on to scenes, and from scenes to the subject itself. They’ve suggested to me – out of the kindness of their hearts – the following modifications:

- Change the protagonist into a lord, taking away any idea of sovereignty.

- Change the wife into a sister.

- Modify the witch’s scene, transferring it to a time when this was credible.

- No dancing.

- The murder off stage.

- Cut out the scene where the names are chosen by lot.

And so on and so forth!!! As you can imagine these changes are quite unacceptable; therefore no opera; therefore the subscribers won’t pay their advance; therefore the government will withhold its subsidy; therefore the management is suing everyone concerned and threatening me with a fine of 50,000 ducats!

The San Carlo management hit on a solution: hire a new poet to rewrite the libretto as Adelia degli Adimari, and set it in 14th-century Florence, in the time of the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. Verdi refused…

The Vendetta in Domino is composed of 884 lines; of these 297 have been changed; in Amelia’s part many have been added, many removed. Moreover I would ask whether the management’s drama has in common with mine:

The title? – No

The poet? – No

The period? – No

The place? – No

The characters? – No

The situations? – No!

The drawing of lots? – No!

The ball? – No!

A composer who respects his art and himself could not and should not incur dishonor by accepting as material for music written on a completely different plane these bizarreries which violate the most obvious principles of dramatic art and degrade the conscience of an artist.

…so the management sued him for breach of contract. Verdi responded by counter-suing them.

The matter was settled out of court; Verdi would revive Simon Boccanegra for Naples, and produce Ballo for Rome’s Teatro Apollo, with changes to satisfy the censors.

(For more information, see Julian Budden’s The Operas of Verdi, Vol. 2, 1978, rev. 1992.)

It’s astonishing, given the turmoil of its creation, that Ballo is so good. It’s one of Verdi’s five best, up there with Don Carlos, Aida, Otello, and Rigoletto.

The opera is one of Verdi’s cleverest, tightest-plotted works. He had the advantage of a libretto by Scribe, master of the well-made play.

Scribe’s scripts are carefully constructed; the situation is clear from the start; the first act establishes the characters and their relationships; and the action moves with inevitable logic through a series of dramatic twists to a surprising but inevitable end that ties all the threads together. The audience is given information whose significance they don’t realise until the cunning author reveals the secret. What a writer of detective stories Scribe would have made!

Somma’s libretto amounts to an Italian translation of Scribe’s, its five acts compressed to three, with modifications. He omits the politics of the French opera – understandably, given the problems with the censors forced the story to be transplanted to New England.

Verdi, though, like other Italian composers, was more interested in the characters’ emotions and relationships than in the historical background. He wanted a taut, swiftly moving drama, with divertissements kept to a minimum. Thus, the ballet becomes a background to the murder, rather than a 25-minute ballet, a spectacular end in itself.

Ballo is in some ways a spiritual successor to Rigoletto. Both are about a capricious tenor nobleman (originally a king), who disguises himself as a commoner, and holds masked balls. He tries to seduce his baritone crony’s woman; the baritone then tries to kill him.

Both are tragedies of errors, with plot twists like a comedy. The death of Gilda in the sack is a bitterly ironic punchline, while Ballo turns upon husband escorting his veiled wife.

“It’s a joke, or madness,” Gustavo says when he hears Ulrica’s prophecy – an ambiguous line that can be read as insouciance / scepticism, or a shaken man trying to pass it off as a joke. The conspirators tell Renato he’s joking when he wants to join the conspiracy. The assassins sing that the tragedy has turned into comedy when Amelia is revaeled to her husband – but it’s no laughing matter for them. And, of course, Renato himself is (partly) mistaken when he believes that the two met at the hangman’s field for a midnight tryst; Amelia only went there to get the herb to cure her love.

The score reveals an unexpected comic side to Verdi. The humour in Rigoletto is black and sardonic; “gaiety”, as Charles Osborne (The Operas of Verdi, 1969) writes, “did not come easily to him”. (Jean-Pierre Ponnelle is right, though, to stage Rigoletto as a parody of Rossini‘s comic opera The Barber of Seville.)

Ballo has a wit and effervescence unusual for Verdi; it sparkles. The score is full of scampering rhythms and triplets, and the delicate instrumentation is astonishing in the composer of Attila. It sounds, often, rather French.

“Ogni cura” has all the high-kicking gusto of an Offenbach galop. The score is Verdi at his most inventive: the staccato, almost whispered Act II trio; the same act’s quartetto finale, with its chorus of mocking laughter; and the dazzling Act III quintet. They are structurally, but not melodically, similar to Auber’s.

The love duet – one of Verdi’s best – shows the influence of the great, epoch-defining one in Les Huguenots. (Listen from “Ebben, si, t’amo!”) Oscar, descendant of Urbain (Huguenots) as much as Auber’s Oscar, straddles the two worlds of opéra-comique and grand opera, as his prototype does in Meyerbeer.

Verdi remains, however, his own man; he assimilates, but is not absorbed. His experience in Paris – Jérusalem (1847), Les vêpres siciliennes (1855) – gave him a new vocabulary, a refinement of orchestration and palette which will flourish in his two great grand operas Don Carlos and Aida, if not Otello.

RECORDINGS

Watch:

Luciano Pavarotti (Gustavo), Leo Nucci (Renato), Aprile Millo (Amelia), Florence Quivar (Ulrica), and Harolyn Blackwell (Oscar), with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by James Levine. New York, 1991.

Listen:

Plácido Domingo (Riccardo), Piero Cappuccilli (Renato), Katia Ricciarelli (Amelia), Elizabeth Bainbridge (Ulrica), and Reri Grist (Oscar), with the Covent Garden Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by Claudio Abbado. London, 1975.

Avoid Solti’s famous 1960 recording, which makes Verdi sound worse than he is, full of coarse brass and percussion, and over-emphatic chords.

STRUCTURE

ACT I

Gustavo’s palace

- Preludio

- Coro d’introduzione: Posa in pace

- Scena e Romanza: La rivedrà nell’estasi

- Scena e Cantabile: Alla vita che t’arride

- Scena e Ballata: Volta la terrea fronte alle stelle

- Seguito e Stretta dell’ Introduzione: Ogni cura si doni al diletto

Ulrica’s dwelling

7. Invocazione: Re dell’ abisso, affrettati

8. Scena: È lui, è lui

9. Scena: Sù fatemi largo

10. Scena e Terzetto: Della città all’ occaso

11. Scena e Canzone: Di’ tu se fedele il flutto m’aspetta

12. Scena e Quintetto: È scherzo, od è follia

13. Scena ed Inno – Finale I: O figlio d’Inghilterra!

ACT II

On the outskirts of town, at the gallows-place. Midnight.

14. Preludio, Scena ed Aria: Ma dall’ arido stelo divulsa

15. Duetto: Teco io sto, Gran Dio!

16. Scena e Terzetto: Tu quì? per salvarti da lor

17. Scena e Coro nel Finale II: Avventiamoci su lui

18. Quartetto – Finale II: Ve’ se di notte quì colla sposa

ACT III

Renato’s house

19. Scena ed Aria: Morrò ma prima in grazia

20. Scena ed Aria: Eri tu che macchiavi quell’ anima

21. Congiura – Terzetto – Quartetto: Dunque l’onta di tutti sol una

22. Scena e Quintetto: Di che fulgor, che musiche

The ball

23. Finale III – Scena e Romanza: Ma se m’è forza perderti

24. Festa da ballo nel Finale III: Fervono amori e danzo

25. Seguito del Finale III. Canzone: Saper vorreste

26. Coro, Scena, e Seguito della Festa da ballo: Fervono amori e danze

27. / 28. Scena e Duettino, e Coro nel Finale III: T’amo, si t’amo e in lagrime

29. Scena Finale: Ella è pura, in braccio a morte

Ballo has always been one of my favourite Verdi operas, the score brim full of invention and variety.

I’d also suggest listening to at least one of the recordings with Callas and Di Stefano (1956 studio under Votto or 1957 live under Gavazzeni). Di Stefano may be more plebeian than Domingo, but he sings with such charm and face and Callas is at her very best as Amelia, her voice wonderfully responsive and secure up to the top Cs. Amelia is a transitional role and requires many of the vocal graces associated with bel canto specialists, though they are often ignored. The studio recording has a supremely dramatic Renata in Gobbi (the way he sings the one word “Amelia” when he discovers the identity of Riccardo’s tryst will haunt you forever) and the live one has the less subtle, but vocally resplendent Ettore Bastianini. Gavazzeni has a tighter grip on the score than Votto. Both are preferable to Solti’s over emphatic style.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll get a copy; thanks for the tip!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very insightful review! I liked how you brought in so many aspects (Meyerbeer, Auber, Verdi’s experience at the Opera Paris). The comparison with Attila was amusing, I would chalk that up to its uniquely “Teutonic” and dark quality. I would say that the exposure to Paris in 1847 saved Verdi’s career if not for Macbeth, which was obviously completed earlier, because otherwise Verdi had hit a low point in 1845-47 with the likes of Masnadieri, Alzira, Giovanna, and Corsaro. Similarly to the W-man, Verdi operas all have distinctive sound worlds or ‘tinta’ (as you well know) and Ballo’s is an attractive mix of comic froth, irony, romance, and poignant tragedy. The love duet is frequently compared to that of Tristan und Isolde, although it is much more sexy and not a philosophical treatise on committing suicide for love. And yes, ‘Una vendetta in domino’ is one of the most awesome titles an opera could have had!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Have you ever heard the 1946 live performance with Mario del Monaco conducted by Nino Sanzogno at Geneva? It is really, really early, so if you aren’t as into dramatic tenors with pyrotechnic mannerisms that isn’t the case at all, he comes off as a normal lyrico-spinto. There is a cut made to Riccardo’s act 3 cavatina, but otherwise it appears to be complete. Another funny little drive bit about the performance was that the chorus is singing in French the entire time while the soloists are obviously singing in Italian! Apparently that was a common practice with Geneva. Bilingual opera, now that is something that should be researched. Maybe if I ever do a PhD….

LikeLike

I’ve heard/seen this opera countless times and I still don’t know which of Those Two Bad Guys is Horn and which is Ribbing. They seem interchangeable. XD

LikeLike

Hello Rowena! You’re obviously a Verdi fan!

You’re right; Horn and Ribbing seem to be interchangeable – one entity with two voices.

LikeLike