- Action musicale in 2 acts

- Music & poem: Vincent d’Indy

- First performed: Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, Brussels, 7 January 1903

- Conductor: Sylvain Dupuis. Mise en scène: Charles de Mer. Décors: A. Duboscq. Costumes: La Gye.

| VITA (20) | Soprano | Claire Friché |

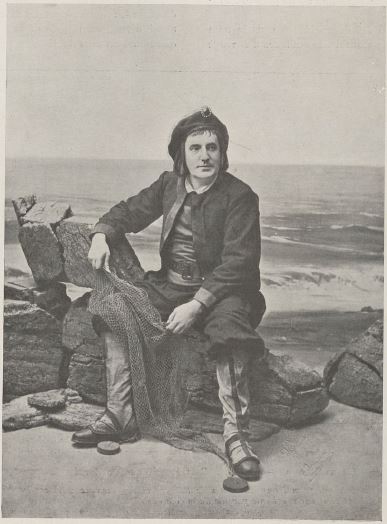

| L’ÉTRANGER (42) | Baritone | Henri Albers |

| ANDRÉ, customs inspector (23) | Tenor | L. Henner |

| Vita’s Mother (55) | Mezzo | C. Rival |

| Madeleine | Sereno | |

| An old woman | Emilie Dalmée | |

| A young woman; 1st girl | Dratz-Barat | |

| 1st worker woman; 2nd girl | Louise Brass | |

| 2nd worker woman; 3rd girl | Adrienne Tourjane | |

| Old Pierre | G. Colsaux | |

| A young man | L. Disy | |

| A fisherman; the smuggler | Ed. Cotreuil | |

| A young sailor; a young fisherman | Eugène Durand |

SETTING: A village by the sea.

L étranger is a jewel of an opera, melancholy and mysterious as the ocean.

It is, like Fervaal, a religious opera; while the earlier work is Frenchified Wagner, a saga of Celts at the waning of paganism, this blends naturalism with the symbolic.

The opera takes place in a poor fishing village. L’Étranger (the word may be translated as both “foreigner” and “stranger”) travels the world, in search of beauty and goodness. The villagers, though, believe he is a wizard, because he is a more successful fisherman.

Vita (“Life”), 20 years old, loves him – although she is engaged to the customs inspector André. L’Étranger recognizes that he has erred in troubling the girl’s heart, and decides to leave the country forever. Before his departure, he gives Vita a magical emerald, once owned by Christ, that calms oceans.

Distressed, she throws the jewel into the sea. The sky turns black; the sea turns green; and a howling storm breaks.

The Étranger sets out to rescue a boat in trouble. Only Vita, touched by his mission, will accompany him. Their dinghy is swept away by the waves. The watching fishermen intone the De profundis.

The story is Wagner’s Flying Dutchman, given a more mystical bent.

Vincent Giroud (French Opera: A Short History, 2010) calls it “a Christian allegory of love”.

Vita, in Giroud’s reading, is Love engaged to Man (André, from the Greek άνδρας). She vows chastity, and turns towards Christ: here, a fisherman, if not a fisher of men.

At the end, René Doire, (L’Art du théâtre) wrote, the sea joined the Ideal (l’Étranger) and Life (Vita) in death which unites them for eternity, new and immortal existence affirmed by Christian faith, the only possible union, the only salvation wished for by folly and wisdom after the renunciation of love.

While Doire (one of d’Indy’s former pupils) thought L’Étranger marked an immense progress in musical art, audiences were less convinced.

The work, Arthur Pougin (Dictionnaire des opéras, supplement 1904) wrote, was coldly received at its première at Brussels’ Monnaie in January 1903, and even more coldly by the Parisians when it was produced at the Palais Garnier that December. “Despite the exaggerated praise of certain critics, the work was completely devoid of dramatic and musical interest.”

Pougin’s criticism is harsh; one doesn’t have to be religious to appreciate the beauties of the score, finer than the bombastic, sub-Wagnerian Fervaal.

d’Indy’s style has significantly changed, as Paul Le Flem (Le Ménestrel, 29 July 1921) wrote. “The musician pays less attention to the poetry of things and the picturesque. His lyricism is more tense and focused. The external details of the drama are of less interest to him, and all his efforts are concentrated on the internal struggle between the two principal characters, Vita and l’Étranger.”

True, the opera is rather talky; much of its two acts consist largely of extended duet/scene between Vita and l’Étranger. The recit in Act I, though, is agreeable on the ear, and more tuneful than, say, Puccini or his ilk. And the second act contains the opera’s most powerful music.

The Act I prelude is luminously beautiful and mysterious, like the Parsifal Vorspiel. “Among the most moving symphonic pages of the score”, Le Flem thought, “one is enthralled by this dolorous and passionate piece.”

The post-Wagnerian, impressionist Act II prelude leads into a jaunty chorus of villagers returning from church, looking forward to hitting the taverns. Note the pizzicato string phrases.

The opera’s musical plums are in this second half. Vita’s “J’attends” is a broad, Wagnerian aria, like a French Liebestod.

L’Étranger’s account of his lonely voyages (“Je suis celui qui rêve »)and his description of the mystical emerald are nobly beautiful; we must turn again to Parsifal or to Jokanaan’s music in Salome to find their equal.

Vita’s invocation to the sea is powerfully dramatic; Indy treats the chorus as an instrument, its wordless vocalising representing the waves and the wind. This scene reaches tragic greatness, Le Flem thought.

We bid his earlier opera a Fervaal to arms; L’étranger, though, is fine and d’Indy.

Listen to

Recording: Montpellier, 2010, with Ludovic Tézier (l’Étranger) and Cassandre Berthon (Vita), cond. Lawrence Foster

Hi, none of the videos can be played in Canada.

LikeLike

Zut!

LikeLike

It’s okay, I’ve read reviews and they are far less glowing than yours. I doubt I’d like it anyway. Re: ten minutes after listening: D’Indy is amazing, wow, it is like Flying Dutchman and Parsifal combined which is better than Tina Turner and Cher combined!

But in all seriousness, the vids are unavailable in the GWN and it isn’t on Amazon Prime Music.

LikeLike

N’oubliez pas, je connais le sens de ce mot!

LikeLike