Well, here we are; a century down, and still not dead.

I’ve always wanted to use my blog to argue the case for obscure works.

This is the first of a new series: presentations of operas that haven’t been performed in living memory; from which at most only a few extracts may have been recorded – but that merit resurrection.

Thanks to Gallica, we can look at contemporary illustrations, set designs, and costume sketches; we can read the opinions of critics of the time. We can, if we’re very lucky, hear singers from the turn of the century perform the most celebrated pieces.

With a little imagination, we can reconstruct these lost operas.

So, without further ado:

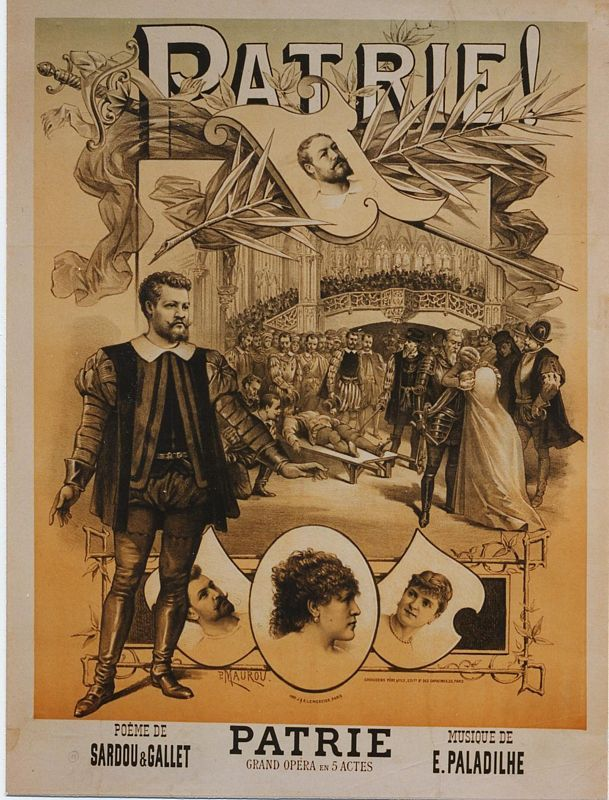

100. Patrie! (Emile Paladilhe)

- Grand Opéra in 5 acts & 6 tableaux

- Composer: Émile Paladilhe

- Libretto: Victorien Sardou and Louis Gallet, after Sardou’s play (1869)

- First performed: Théâtre de l’Opéra (Palais Garnier), Paris, 20 December 1886

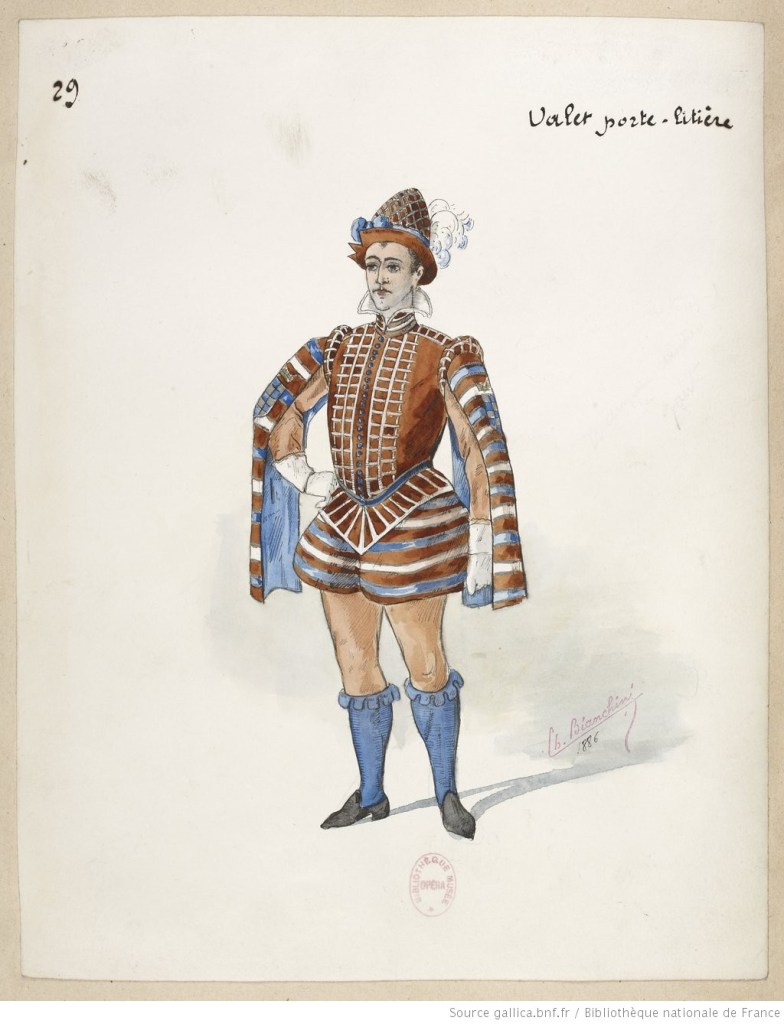

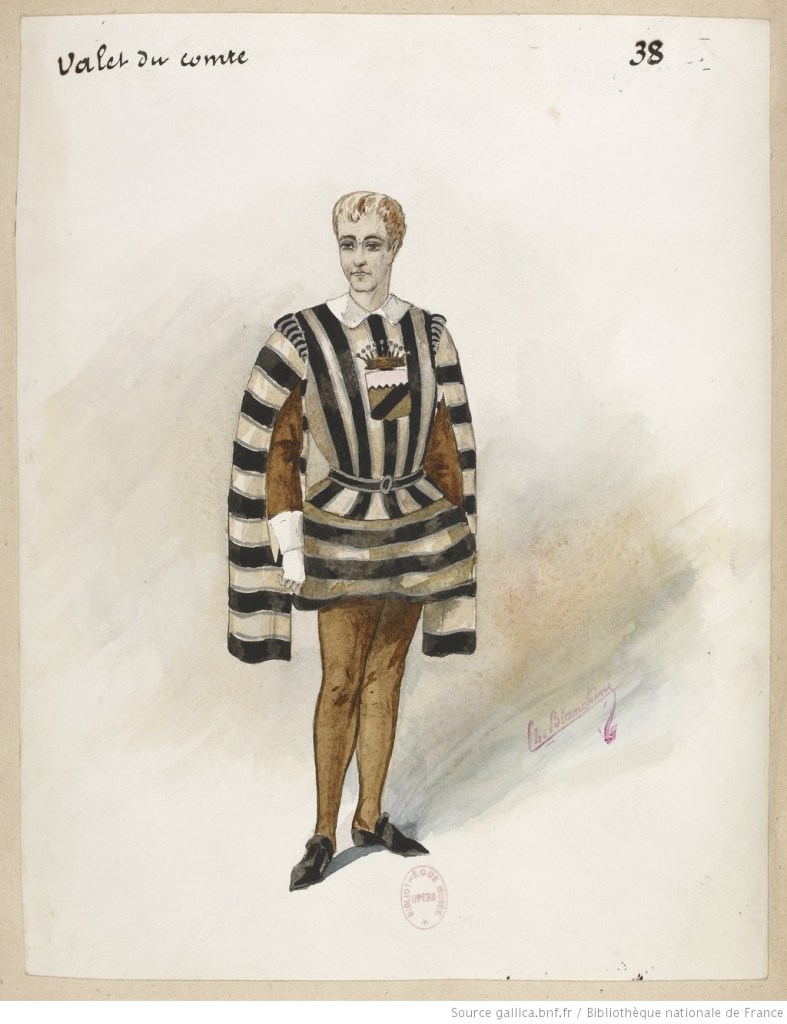

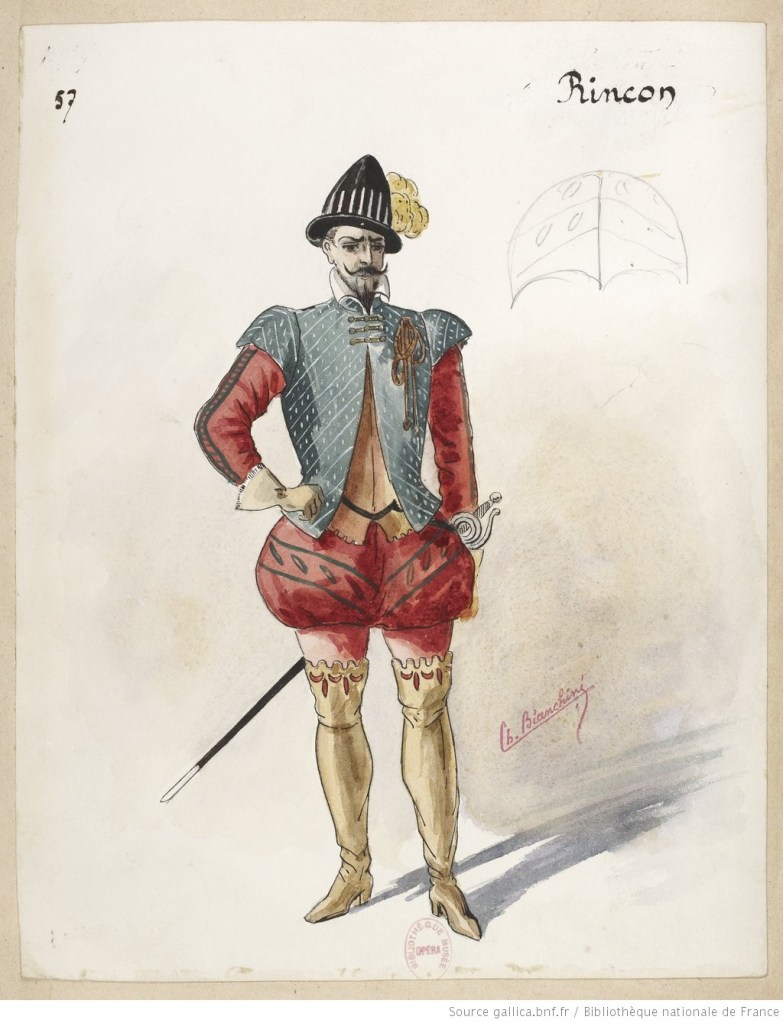

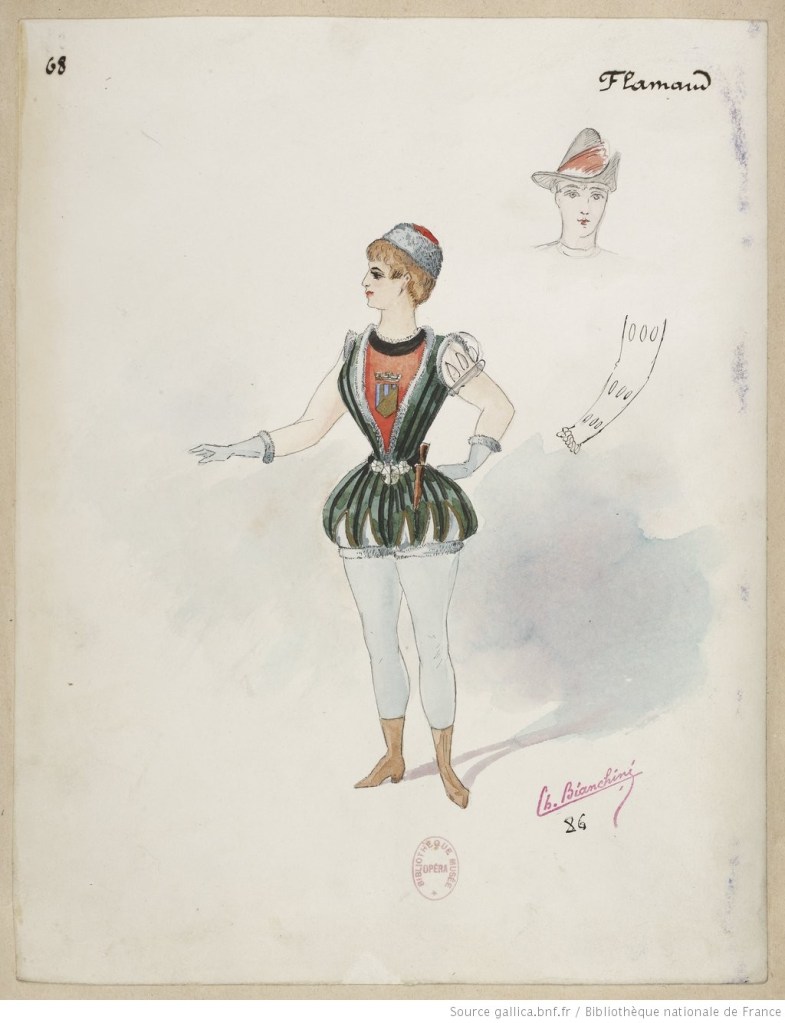

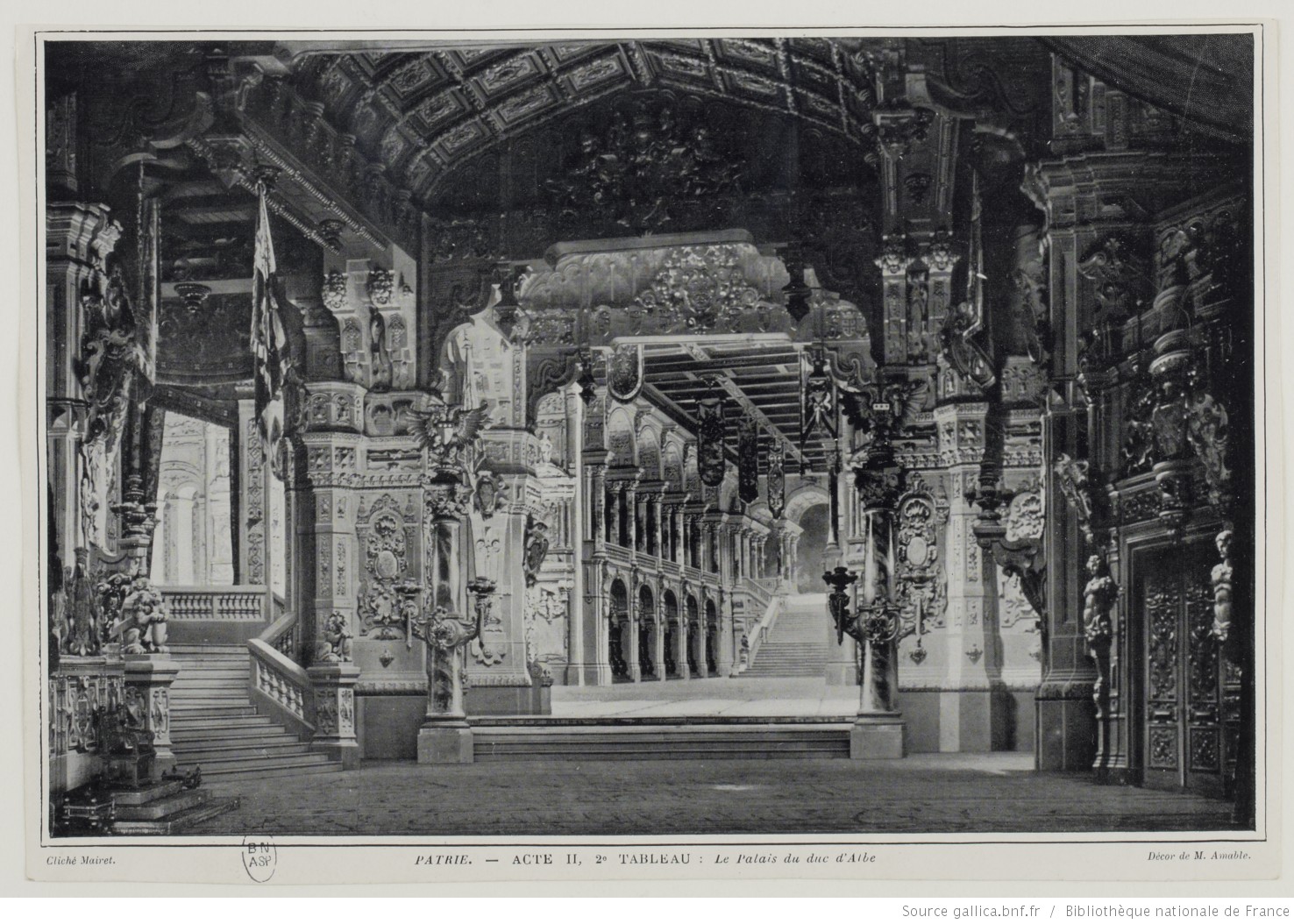

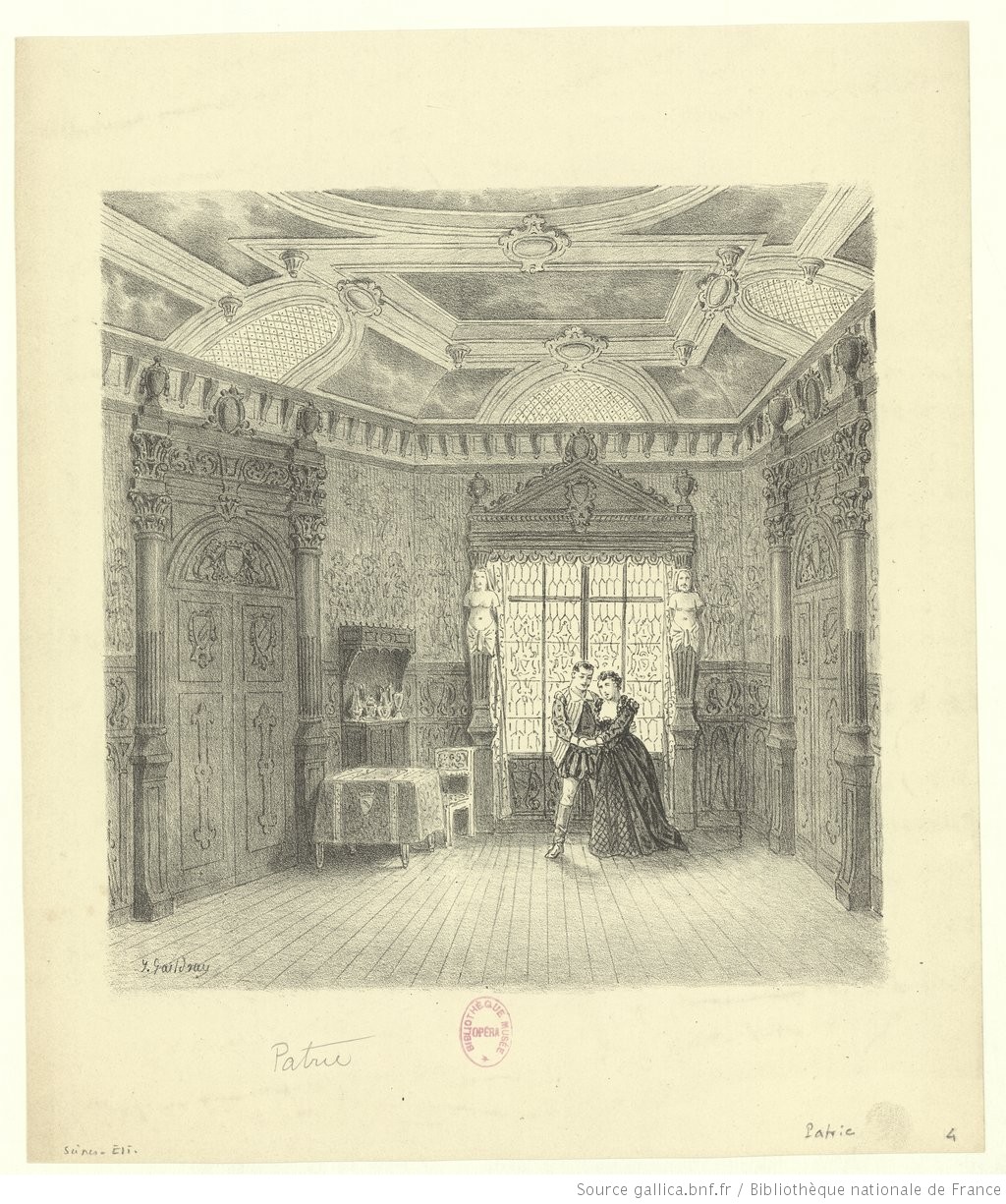

- Conductor: Jules Garcin. Mise en scène: Pedro Gailhard. Décors: Poisson (1), Henri Robecchi & Amable (II & V), Auguste Rubé, Philippe Chaperon & Marcel Jambon (III), Jean-Baptiste Lavastre (IV). Costumes: Charles Bianchini

Patrie! is the last great French grand opera.

Set in Brussels in 1568, it is a powerful historical epic of the revolt of the Spanish Netherlands, with a more intimate drama of adultery, betrayal, and revenge.

It is based on Sardou’s historical drama (1869), originally intended as a libretto for Verdi. Paladilhe’s opera, in fact, had a better run in Paris than Don Carlos, which also deals with the Dutch Revolt.

The opera placed Paladilhe in the front rank of French musicians. Patrie was a heroic, noble work, perhaps the most powerful and moving since the glory days of Halévy’s Juive (1835), and Meyerbeer’s Huguenots (1836) and Prophète (1849).

Patrie, in fact, was one of the most popular French operas of the period. After its première in 1886, it was performed 92 more times in Paris (seven short of the magic 100); regularly in the provinces; and successfully in Italy.

“If there was a swan-song for the historical drama side of the genre,” Steven Huebner (Cambridge Guide to Grand Opera) wrote, “this was it.”

The work was last performed in Paris on 8 September 1919. Two arias, “C’est ici le berceau”and “Pauvre martyr obscur”, both beautiful and nobly grand, were recorded by bass-baritones in the first half of the 20th century. One other aria and a duet have also been recorded.

Frankly, I’m surprised the great Belgian bass-baritone José van Dam never recorded this opera. The role of the Flemish Rysoor –at once noble conspiracy leader and suffering husband – would have been a great fit for the Brussels-born singer.

I first came across the work on David Le Marrec’s Carnets sur Sol website; he calls it something really cool that deserves to be remounted and recorded. “Like the best Meyerbeers, its heroic yet playful tone could quite seduce the general public, also fans of fans of Verdi and Gounod, and perhaps more generally of French opera.”

The Composer

Émile Paladilhe (1844–1926) was the youngest ever recipient of the coveted Prix de Rome.

Born in Montpellier on 3 June 1844, his first musical training came from his father, Dr Alcide Paladilhe, a keen amateur flautist; and a Spanish abbé, Sebastien Boixet, who played the cathedral organs.

At the age of nine, Paladilhe went to study at the Conservatoire de Paris, with a bursary from his home town. Marmontel taught him piano, Benoist organ, and Halévy composition. He was one of Halévy’s favourite students; the composer of La Juive noted in him an extraordinarily precocious musical talent.

As a boy, Paladilhe apparently knew Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier by heart. In 1856, at the age of 12, he received the second piano prize, and the first accessit for fugue. The next year, he was awarded the first piano prize, and accessit in organ. In 1859, he took the first accessit in organ, and an honorable mention for the concours de Rome. Finally, in 1860, at the tender age of 16, he was awarded the prix de Rome with the cantata Ivan IV, as well as the second organ prize.

While the jury was deliberating, Paladilhe walked in the Institut’s great courtyard. The judgement over, Berlioz passed through, on his way home. Paladilhe stopped him:

“Is it over, monsieur? … who obtained the prize?”

“What’s that to you, kid?” (said the composer of Les Troyens, doing his best Jimmy Cagney impression)

“But, sir, it interests me a lot!”

“Well, since it interests you so much, it’s Paladilhe who has the first prize!”

“Really, sir? – but I’m Paladilhe.”

“What, it’s you, toddler?”

And Berlioz, picking him up from the ground, kissed him on both cheeks, and predicted a great career.

Paladilhe’s career had, in fact, already started. While studying, he performed as a piano virtuoso with enormous success, and composed piano pieces, romances, and even opera.

He was 14 years old when, in one of his concerts, he performed the music of a one-act opera, Le Chevalier Bernard; 15 when he produced, in the same conditions, La Reine Mathilde, an opera in three acts.

Auber, director of the Institut, personally recommended him to Heugel; his first three piano pieces were published, under the title Premières Pensées.

As a pianist, the little prodigy astonished audiences by the perfection of his technique, the charm of his playing, and his marvellous memory.

Almost still a child, all the laurels of the Conservatoire have already crowned his brow… What we have heard from Paladilhe’s dramatic essays promises a melodist. He writes very well, and his works testify that he knew how to profit from the high teaching of Halévy. Until we can proclaim him a great composer, we can state that his talent as a pianist is most remarkable. Out of the school of Marmontel, he has the purity, the elegance, the brio, the poetic charm. A trio of Mendelssohn performed with MM. Rignault and Chaîne, a romance without words by the same master, a pretty Polonaise by Marmontel, a Chopin nocturne, a Bach fugue, and a lovely Stephen Hellen tarantella showed how successfully the young virtuoso approached all styles. He performed three pieces of his own composition. All contain charming things; the rondo scherzo, above all, is a happy inspiration; he performed them with great clarity and taste, simply, without thumping, and yet with all the energy and power of sound that one can have at fifteen.

Quoted in ANNALES POLITIQUES ET LITTÉRAIRES, December 26 1886

While at the Villa Médicis, he became a close friend of Gounod. The Mandolinata, “delicate and melodious souvenir of his stay there” (Journal officiel de la république française),was on everybody’s lips throughout Europe.

The young virtuoso seemed to give sure promises for his future – but his operatic career didn’t properly start until 1872, twelve years after his return from Rome.

He wrote a series of graceful but unsuccessful operas, with badly constructed, uninteresting libretti (Albert Dayrolles, Annales politiques et littéraires).

Le passant (opéra-comique in 1 act, 1872) was a failure, despite an attractive score; Félix Clément (Dictionnaire des opéras) thought the libretto was to blame, lacking any of the elements proper to a libretto. Arthur Pougin (Le Ménestrel) considered its music more the work of a dreamer than a real stage musician.

L’amour africain (opéra-comique in 2 acts, 1875), based on a Prosper Mérimée play, was considered too violent and noisy, and had almost no success.

Suzanne (opéra-comique in 3 acts, 1878) was liked more than Paladilhe’s earlier efforts: Clément called it a charming work, suffering from a too improbable plot. Despite a delightful first act, Pougin wrote, it wasn’t successful.

The historical opéra-comique Diana (3 acts, 1885) did not inspire the composer; it was found too cold and heavy, Clément wrote, and left the public indifferent.

Between times, Paladilhe published compositions, collections of 20 mélodies and Six melodies écossaises – full, Pougin wrote, of charm, grace, and freshness. These include the exquisite Psyché.

All that time, he had his eye on Patrie!. It was a critical and popular success – but his last performed opera. Two later works – Vanina (composed 1890) and Dalila (composed 1896) –never reached the stage.

From 1890, Paladilhe devoted himself to church music. He composed motets; two masses, one for Pentecost, and one on St François d’Assise.

Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (1892), an oratorio in four parts, was composed on a poem by Louis Gallet, at the request of the Bishop of Montpellier.

He died at his work desk, while writing a Tu es Petrus, a cappella, on 6 June 1926.

“Paladilhe is not one of those we meet frequently,” Dayrolles wrote. “He lives quietly in his apartment on the rue Mansard, and rarely goes into society or first performances.

“His photograph itself is visible in no shop window. We would look in vain for him among the people who compose the Tout-Paris of each day. He lives at home, and is fully absorbed in the study and practice of his art. He even abandoned his piano, which he once used to cultivate so successfully. His nature is balanced and thoughtful. He is modest, and avoids opportunities to talk about himself. Nevertheless, it must have been sweet for him to hear his name in all the newspapers, attached to his cherished Patrie, which he coddled so long, and which all Paris was in a hurry to see this week…!”

Synopsis

| LE COMTE DE RYSOOR | Baritone | Jean Lassalle |

| DOLORÈS, his wife | Soprano | Gabrielle Krauss |

| KARLOO | Tenor | Valentin Duc |

| LE DUC D’ALBE | Bass | Edouard de Reszké |

| RAFAËLE, his daughter | Soprano | Rosmann |

| LA TRÉMOÏLLE | Tenor | Antoine Muratet |

| JONAS, town bellringer | Baritone or bass | Bérardi |

| RINCOÑ, Spanish officer | Bass | Sentein |

| NOIRCARMES, provost of Brabant | Bass | Dubulle |

| VARGAS, secretary of the Council of Troubles | Tenor | Sapin |

| DELRIO, advisor | Bass | Crépaux |

| GUDULE | Duménil | |

| UN OFFICIER D’HONNEUR | Balleroy | |

| UN OFFICIER | Boutens | |

| MIGUEL | Girard | |

| GALÉNA | Laffitte | |

| BAKKERZEEL | Hélin | |

| CORNÉLIS | De Soros |

SETTING: Brussels, 1568, under Spanish occupation.

The Duke of Alba, worthy lieutenant of the implacable Philip II, and the Council of Troubles are hanging, beheading, or burning alive the Protestant Flemish as heretics.

The oppressed Flemish revolt. The Comte de Rysoor plots an insurrection to oust the Spanish with the help of William of Orange. His wife, Dolorès, is the lover of Rysoor’s friend Karloo, captain of the guard.

Rysoor learns that he has been betrayed, and tells Dolorès that he will kill her lover. To save him, Dolorès betrays the conspiracy to the Spanish.

Rysoor spares Karloo’s life on condition that he will kill the traitor, whomever they may be.

Karloo exposes the infamous woman, kills her, and mounts the pyre with the leaders of the revolt.

Paladilhe started composing the opera some ten years before its performance. Sardou himself wanted to see the play turned into an opera; indeed, he originally meant it to be an opera libretto, for Verdi. (The combination of adultery and a popular uprising recalls La battaglia di Legnano.)

Verdi refused to compose for Paris, after falling out with the Opéra director Perrin when rehearsing Don Carlos. He wanted to make it into an Italian opera, but Sardou preferred to turn it into a French stage play.

Gounod told Sardou that Paladilhe wanted to make it into an opera; he urged his case, but Sardou resisted. Paladilhe then asked the Académician Legouvé, his future father-in-law, to intercede. Sardou consented to let Paladilhe set the first act of the opera, and judge when he’d seen its effect on him.

“He made me hear his Choeur d’ouverture,” Sardou wrote. “I was surprised to find qualities of strength and energy I’d not suspected. Then he played his finale; I was completely won over, and I set to work. I rewrote the scenario myself, and left it to Gallet only to write the verses.”

Knowing that this work could have an enormous influence over his whole career, Paladilhe did not want to hurry (Dayrolles, Annales politiques et littéraires). He wanted to bring all his energy, concentrate his strength, and therefore work only at those times when he felt himself enveloped in the atmosphere of the opera.

Arthur Pougin (Le Ménestrel) considered it one of the most outstanding works in a very long time, placing Paladilhe at once in the front rank of young French musicians.

The work, he wrote, was at once heroic and pathetic, throbbing with passion, and of a truly epic grandeur. The libretto was one of the most beautiful opera poems imaginable, indeed one of the most powerful and moving since Halévy’s Juive (1835), and Meyerbeer’s Huguenots (1836) and Prophète (1849).

Victor Wilder (Gil-Blas) thought it had a place in the repertoire next to La juive and Thomas’ Hamlet (1868).

The anonymous critic of Le petit journal also praised this magnificent, grandiose work, a dazzling manifestation of the new music; like Pougin, he henceforward placed Paladilhe in the first rank of dramatic composers.

Camille Bellaigue (L’année musicale) agreed this strong, sincere, elevated work had the most beautiful libretto since Les Huguenots. It lacked only a little bit of personality (individuality) to be a really great work. The score was like a synthesis of masterpieces (Meyerbeer, Rossini, Verdi, Gounod), worthily conserving the tradition of beauties already known and always loved.

A. Boisard (Le monde illustré), in a generally negative review, thought it borrowed largely from Meyerbeer and Gounod; there was nothing new, but the retellings pleased the audience.

On the other hand, the Petit journal thought the score too modern (relying too much on harmony and instrumentation rather than melody).

Synopsis mainly based on Le Petit journal (18 December 1886)

Libretto

Act I: La place du Marché

1: Introduction: Versez, versez (Chorus)

No overture. A short introduction,and the curtain rises on the place du marché de la Boucherie, Brussels. Spaniards play and sing around a fire, celebrating their victory in battle.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Honestly rhythmic.

2: Scène et Air: Marchez donc (La Trémoïlle)

Enter the Comte de Rysoor, and the Duc de la Trémouïlle (a French prisoner, whose ransom has been fixed at 100,000 écus). Both are Calvinists; offstage,

the Inquisition kill their fellow believers. Trémouïlle, the king’s friend, describes how the Spanish captured him while he fought for Nassau.

- L’année musicale(Bellaigue): Hors-d’œuvre that takes up too much time on the threshold of the drama, and, musically, is not worth the pretty orchestral refrain, nor the clear recitatives that precede it.

- Gazette artistique de Nantes (Wilder): A piquant recitative

- Le monde illustré (Boisard): Nicely written

- Le ménestrel (Pougin): Very sonorous

3: Scène: Oui, c’est le Carnaval (La Trémoïlle, Rysoor)

It’s Carnival – but the tribunal of the Inquisition doesn’t relax. Under the presidency of Noircarmes, the Council of Troubles execute the Flemish (Protestants) as religious heretics.

Pour affirmer sa puissance / La ruine est partout, et partout le gibet ; / Tout soldat est bourreau ; certain de la sentence, / Pourvu qu’il tue, il peut tuer comme il lui plait ! Voila la sanglante furie/ Que promènent sur notre sol / Les oppresseurs de la patrie !

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Drags a little.

4: Scène du Tribunal

a: Entrée du Tribunal: C’est un froid mortel

The tribunal (the grand prévôt Noircarmes and his acolytes) arrives to judge the prisoners. Karloo Van Der Noot, captain of the city guard, is ordered to disarm his soldiers before the next dawn; if their arms are not at the town hall, they will all be hanged.

b: Chœur et Air du Sonneur: Jonas, Jonas (Jonas)

Jonas, the bellringer who will later have a beautiful death, enters.

Mes cloches ont perdu leur gaité coutumière,

he says, when asked why he doesn’t ring happy tunes. Noircarmes orders him to play Spanish songs on the bells, rather than the old Flemish ones – if not, death.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Best of all. After a well-conducted choir, the bell-ringer’s air appeals to us by its picturesque accompaniment, by its double character of bonhomie and plebeian valour, by its joyful humour, so quickly and so sadly restrained. It is at once humble and proud, this song of the bells that were talkative yesterday, dumb today; it is like their guardian, who trembles, but who knows how to die. This page announces one aspect of the drama, its popular and touching side.

- Gazette artistique de Nantes (Victor Wilder): A piece of an equally happy invention and style.

- Le monde illustré (A. Boisard): The bell-ringer Jonas only has one song, whose dig-ding-dong, in chorus, made all the audience shout encore.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): Very fresh, and so well performed by M. Bérardi that the public wanted to hear it again.

The aria was also recorded by Emile de Gogorza in 1911.

c: Chœur et Ensemble: Les prisonniers !

The prisoners are brought on; the women and children beg for pity on their knees.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): Of a pretty character

d: Scène et Arioso: Qui vient donc ? (Rafaële)

Rafaële, daughter of the Duke of Alba, appears; she has pity on the unfortunates, and orders them to be freed.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): A charming passage… Decidedly, M. Paladilhe has the secret of tunes; this one is exquisite. It soothes all threats, all complaints, and over the veiled murmur of the oboes, the flutes, when a mysterious horn hovers, one listens in half-silence, and softly whispers the young girls’ proverb: “It is an angel passing.”

- Le monde illustré (Boisard): Of vague interest

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): By itself a little pale, but Mme Bosman sings it in a delightful way

e: Angelus: Libres ! libres !

- Le petit journal: A very moving Ave Maria, of exquisite musical craftsmanship

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): The ensemble, although well constructed, faithfully recalls the phrase of [Gounod’s] distraught Marguerite: Seigneur, accueillez la prière des cœurs malheureux !

- Le monde illustré (Boisard): One of the most striking pages … of a sufficiently religious character

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): The choral prayer, with its accompaniment of bells and horns, and above all the symphonic fragment that follows, which is exquisite

f: Scène: Tout n’est pas dit, Messieurs

g: Scène et sortie du tribunal: Vous entendez ?

Rysoor, who has secretly been to see the Prince of Orange, is denounced as having escaped his house the night before. The soldier Rincoñ, lodging with Rysoor, says that he saw a man leave Rysoor’s room that night. The Spaniards assume the man was Rysoor, and release him.

5. Scène finale et rétraite: Un mot je vous en prie

Rysoor questions Rincoñ, and deduces that his wife has a lover. He has one clue: Rincoñ wounded the man in his hand.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Here music attaches to the action, pushes it, precipitates it; the orchestra is moved; bursts of anguish make it struggle and protest against Rincoñ’s affirmations, and suddenly Rysoor bursts out. The movement is really beautiful. Night is coming, bringing loneliness and silence to the oppressed city. The retreat sounds and the patrols pass. « Tendez les chaînes ! » cry sentinels in the distance. Rysoor is always there, mourning his honour and his love, feeling the grip of the horrible truth tightening. Here it is for the first time, that sincere music of which we spoke earlier, music from the heart which one must love, and whose very cordiality would absolve from more than one reproach.

ACTE II

1er tableau: Chez le Comte de Rysoor

6. Entracte et scène: Personne n’est venu (Dolorès)

Dolorès is waiting for Karlo; she struggles against her love.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Her beautiful opening phrase: J’ai prié tout le jour, could well be the most coloured of all her rôle.

7. Duo: Enfin ! toi ! c’est bien toi ! (Dolorès, Karloo)

Karloo arrives; ashamed, he rages against himself: Je veux arracher cet amour de mon cœur ! But Dolorès cajoles him, and he falls at her feet.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): The first part is a little pale, but becomes more energetic as it approaches the end.

8. Scène et Chœur: Le Seigneur Comte

Rysoor tells his friends that William of Orange is in Flanders; all is ready for the uprising; this very night, at the Hôtel de Ville, a general meeting; if everything is favorable, the great bell will ring loudly; otherwise, the funeral knell. Dolorès has heard everything, hidden behind draperies. (Yes, just like in Les Huguenots!)

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): The plotting scene is made entirely from two themes from another conspiracy, that of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell: same phrase on the violins, or almost, as at the entrance of the canton of Uri; same response from the chorus on these words: Guillaume, tu le vois !

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): Excellent scene, treated in rapid declamation and full of firmness

9. Duo: Ah ! maintenant à moi (Dolorès, Rysoor)

Having settled the affairs of the country, Rysoor wants to settle his own. He demands that his wife explain her conduct; the wretched woman confesses that she has a lover.

“You have only loved one mistress: Your Country ! [Votre Patrie !]” Dolorès says. “She is your only virtue. Your heart has never beaten. My country is love!” she says. “What do lost liberty and your dead Flanders matter to me?”

She dares Rysoor to kill her; no, he replies, he will kill her lover – and he will recognize him by his injured hand.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): It’s a very powerful page, very pathetic, of a warm colour, and, if one can say it,of a violent emotion, which produces a profound impression. I note, in this piece, the author’s very artistic disdain for the final effect, because it ends, or rather it stops suddenly, without the listener being aware of it, to let him hear the masques singing in the street.

2ème tableau: Fête au palais du Duc d’Albe

10. Passe-pied et scène

Ballet

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): A short episodic scene mingled with dances prepares the arrival of an immense galley, from which descend immediately – escorted by allegorical figures of Power, Justice, Peace, and Abundance – representatives of all the nations and towns subject to Spain. This brings, naturally, the divertissement, whose music is always distinguished, full of elegance and sometimes exquisite. There are, in order, a charming Sicilienne, a pretty pas of Indiennes, an entrée of Flemings (in which a phrase on the pistons detonates a little too much on the general background), then, after a brilliant ensemble, the first echo of the première danseuse, a pas de dix whose flexible rhythm is reminiscent of the divertissement in Hamlet, an adorable waltz, whose song, entrusted to the clarinet, is deliciously accompanied by the harps, and finally a very lively ensemble, full of colour, movement, and warmth.

- Le petit journal: Set with exquisite taste. … All these groups in various and shimmering costumes dance in evolutions – very graceful, before and after the astonishing, the prestigious performance of Mlle Subra.

- L’annéemusicale (Bellaigue): It’s brilliant, sometimes too brilliant. The piston-horns, too dear to the composer, take vulgar liberties there, a little frivolously; but the clarinet and the harp unite ingeniously to follow the flight of the charming Mlle Subra. Let’s still mention a beautiful effusion of violins while Mlle Torri, noble heiress of Mlle Marquet, organizes the divertissement… At the last pages, like in Faust, we hear the appearance of Phryné.

- Le monde illustré (Boisard): Distracts from the action for too long. It’s a lot of consecutive joy. What becomes of the unhappy Flemish during this time? There’s a great risk that we will have had enough before the end of this divertissement. Otherwise it is well ordered, and shows us Mlle Subra, more and more charming, in the whirlwind of a waltz whose fine carving contrasts with the lack of originality of the other numbers.

11. Madrigal: On ne saurait rêver (La Trémoïlle)

La Trémoïlle admires the performance.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Very courtly… with its fine harmonies

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): Delicious and too short

12. Pavane et Scène: Belle rebelle (Rafaëlle, La Trémoïlle)

The pavane is resumed. When the party is over, Rafaële, who is trying to gain popularity, wants a patriot to give her his hand, and accompany her. They all refuse. But Karloo intercedes; she is a woman; a good angel for the unfortunate. He bows to the Duke’s daughter. The affront has, nevertheless, left the poor child indignant.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Quite exquisite, with a hint of melancholy, the pavane sung with mouths alternately open or closed.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): The danced chorus is a real gem, with a sweet sound, an enchanting rhythm, and slightly archaic; half-tinted, it gives the impression of a musical pastel.

ACTE III: Chez le Duc d’Albe

Entr’acte

13. Scène et arioso: Maître Charle (Albe)

The Duke of Alba orders the executioner to hang all the fanatics,rebels, and heretics. The brewers and taverners have all shut their shops, as if to defy him, and refuse the tax of 10 deniers. Rafaële appears, and tells him what happened at the party.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): In the scene between the Duke and his daughter, I note a very pretty cantabile, unfortunately crushed by M. Éd de Reszké’s powerful voice, which the singer does not sufficiently know how to hold back.

14. Scène et trio: Que me veut-on ? (Rafaële, Karloo, Albe)

Karloo arrives to give up his sword. On his daughter’s request, the Duke names him captain of his guards. Karloo’s refusal throws the Duke into a state of wild rage.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): The trio is worthless – the tenor’s rhodomontade is only a vulgar rat-plan-plan. But all Albe’s recitatives merit attention, and Rafaële’s sweet plaint: Hélas ! j’espérais tant ! is moving. These are quick and personal traits which do a lot for the silhouette of a character.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): Very well treated with the three voices.

15. Scène de la dénonciation: Pardon Monseigneur(Dolorès, Albe, Vargas, Delrio, Noircarmes

A woman is announced. It is Dolorès; to save her lover, she must denounce her husband. Il est, dans cette ville, un homme que je haïs. The Duke of Alba and three of his officers force Dolorès to reveal the names of the conspiratorial leaders (quintet). Dolorès tells all, but she claims a safe conduct for Karloo. “Karloo!” exclaims the Duke. “A wretch!” In vain does she implore grace; the Duke pushes her away, and shouts to her: “Well! Pray for him, if you love him!” And she falls fainting, uttering a heartrending cry.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): One of the best conducted scenes heard at the Opéra in a long time. Without deviating,without faltering, with happy modulations, varied rhythms, always natural and almost necessary, with short pauses, where new impulses are resumed, ça marche [play on both “walk” and “work”], running to the final explosion. It begins with Dolorès’s appearance at the Duke’s home, and the bold apostrophe: Êtes-vous sur de voir encor demain, Monseigneur ? The rest is harsh, resolute like the hatred of this woman, sometimes with anguish, well rendered in the phrase: Ah ! je sais quel mépris vous allez concevoir à m’entendre ! sometimes with redoubled fury. All these recitatives are by a master. From the first confession, terror seized Dolorès; a cry of remorse escapes her, one of those cries that M. Verdi would not renounce. It is too late; Albe and his officers press the wretch, and snatch, panting, the details, the proofs of the complot. Here, even M. Paladilhe’s orchestration is eloquent: the saxophone and trombones answer each other, and the opposition of this ominous threat and that copper brilliance reinforces the opposition of the voices and the powerful emotion. Once again, the distraught phrase interrupts the villainous confidences; it reappears in the orchestra, but plaintive, vanquished this time, crying softly for her betrayed country, humble as the poor bell-ringer she seems to have been unable to defend. Finally the recurring phrase is with Dolorès at the name of Karloo; furious, it breaks the iron circle that surrounded it, and, on the highest summit of this magnificent scene, lights the last ray and the last flame. If M.Sardou, as it was said, wanted always to keep first place in this opera, here at least it was removed from him.

- Gazette artistique de Nantes (Victor Wilder): The capital scene of the third act … The breathless tale of the wretch,the Duke’s demands to know the smallest details of the conspiracy, his acolytes’ short and pressing questions, Dolorès’ remorse when she realizes the horror of her crime and the cry of her despair when she realizes that she has betrayed her lover by selling her husband; all this is translated with a great accent of truth and a lot of pathetic force.

- Le mondeillustré (A. Boisard): Paladilhe drew the odious figure of Dolorès without vigour. The great scene of the denunciation, the culminating point of the role, walks slowly and crawls when it should run, and the music weighs down the dialogue that was so rapid, so headlong,so thrilling in the play.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): The situation is powerful, dramatic, heartbreaking … all this scene is masterful, masterly written, animated by a great breath, and Mme Krauss has shown herself admirable.

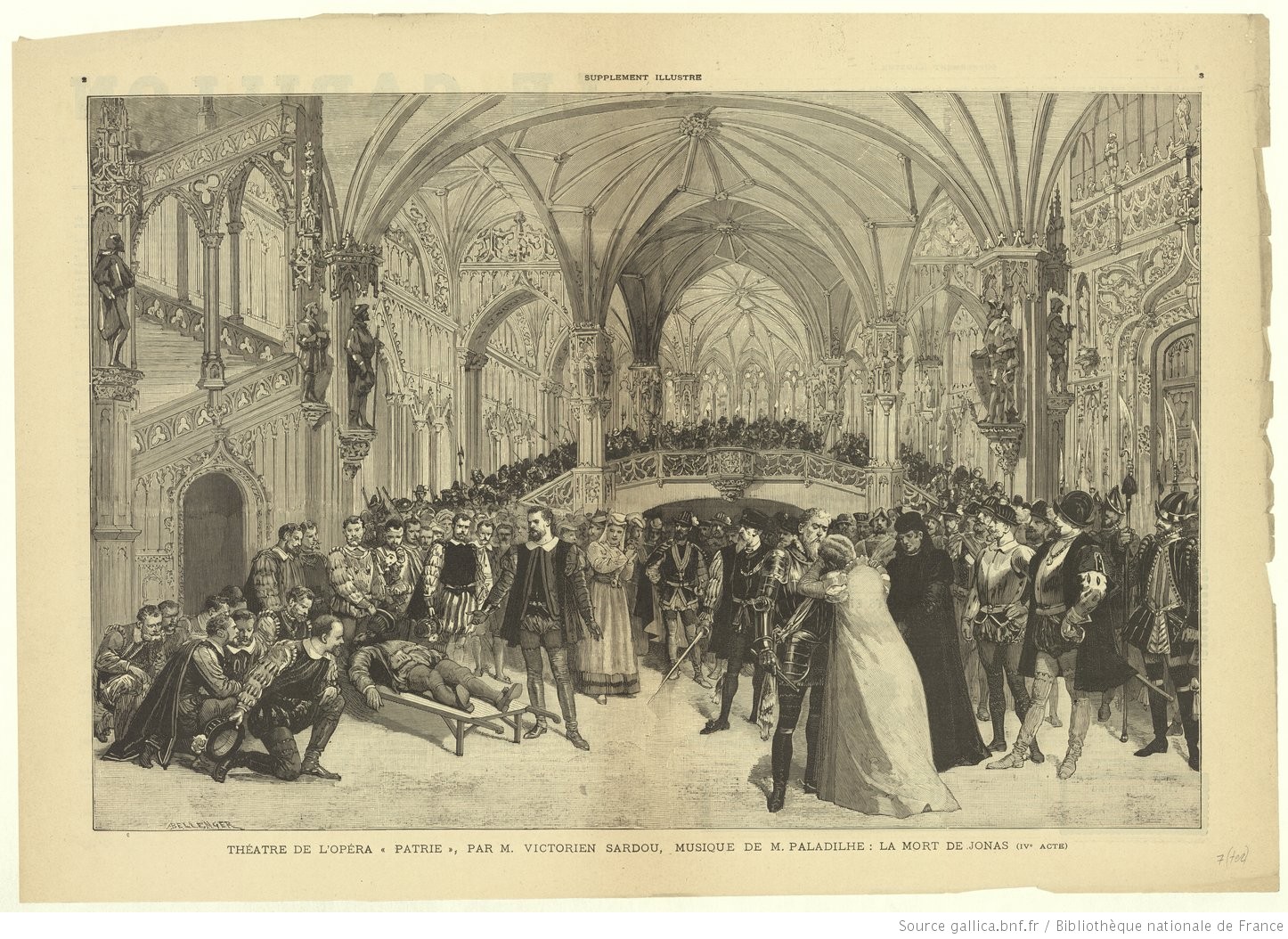

ACTE IV: L’Hôtel de Ville

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): But here truly is the culmination of the work, the act of the Hôtel de Ville. The drama, the music, the staging, everything contributes to its extreme power. Here, emotion is always growing; the situation, at first dramatic, becomes gradually terrifying, and is unraveled in a tremendous explosion.

Introduction

16. Scène et air: Par ici ! doucement ! (Rysoor)

The Flemish are assembled at the town hall, in the deserted asylum, the profanated sanctuary of their liberty. They arrive, announced by a melancholy horn phrase, and Rysoor addresses them.

The aria was recorded by Charles Cambon and Robert Couzinou.

C’est ici le berceau de notre liberté

Ici, nos pères ont fondé

Les lois que nous allons défendre !

Je crois les voir toujours et je crois les entendre

En ces lieux où battait le cœur de la cité !

Plus sinistre est la nuit, plus joyeuse est l’aurore !

Oui, malgré l’Espagnol, ce cœur palpite encore,

Ce cadavre est vivant. – Aux créneaux du beffroi,

Spectre vengeur de la Patrie,

Aux coups du tocsin, il se dresse et crie :

« O peuple flamand, lève-toi ! »

Le peuple entend ! il vient ! … Sa grande âme frissonne !…

Il vient, bravant tous les défis !

Il sait pour qui lutter !… Cette cloche qui sonne,

C’est l’appel déchirant d’une mère à ses fils !

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Ah ! the superb speech! After the most dramatic page in Patrie ! here is the most musical. Such an inspiration is one which suddenly raises the level of a work; it is the mountain from which one discovers kingdoms. Let’s enjoy a little of the horizon; until the end of this fourth act, we are on the heights. Rysoor, the only character created by M. Paladilhe, stands here in all his height. It was perilous, this aria, and what fear we had of the bravura too common to patriots in music! What a surprise to hear noble chords, to follow, after an august recitative, a magnificent expansion of sentiment and melody! The harps vibrate, and on their wings rises the incomparable voice of M. Lassalle; the trombones now accompany the prophetic visions with their solemn song, and, from their mouths of copper, sings the soul of the country. For our honour and our joy, more than one contemporary opera touches, if only for a minute, genius. Patrie! does more than touch it with this admirable hymn of hope and liberty.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin) A superb aria of a noble and beautiful character, grandiose, which the harps and trombones marvelously accompany.

17. Duo: Je veux les plus vaillants ici (Karloo, Rysoor)

Rysoor indicates as chief Karloo; the rebels retire and wait for the hour of revolt. Karloo doesn’t have his sword, which he must have left in the hands of the Duke of Alba. Rysoor hands him his – and sees the scar on his friend’s hand.

The lover of his wife!

Karloo admits his guilt; he was bewitched by the evil woman. “Kill me,” he says.

After a struggle, Rysoor exclaims:

“Death! What does your death matter to me ? I forgive you, but: You have taken my honour, give us liberty!”

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Contains a moving plaint: Ah ! malheureux que j’aimais tant ! which finishes with a reminiscence: the cry of Sapho on her rock crowns the beautiful lament of the betrayed Rysoor.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): Then the pathetic duo in which Rysoor recognizes in Karloo the lover of his wife, the friend who so basely betrayed him; this duo – sometimes touching, sometimes vehement – is divided into several episodes, of which one of the most moving is Rysoor’s sorrowful phrase: Ah ! malheureux que j’aimais tant, Voilà ce qu’il a fait pourtant ! whose despairing tone draws tears from the listener.

18. Scène et chœur: Seigneur, tous nos hommes sont là

It is the hour of the uprising. The conspirators return.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): In Karloo’s appeal to his companions, reminiscences once again, of Guillaume Tell this time, and some rather thin oboes, but movement and heat.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): From this moment, the action rushes ahead. The return of the conspirators, the taking of arms, the charge that rings, the first rumours of treason, the fight, the shots, the entry of the Spaniards,the attempt by Rysoor and his friends to escape, stopped by the arrival of the Duke of Alba, the scene of the bell-ringer, the murder of the latter, his corpse pierced with bullets, Rysoor’s grieving over his body, all this is rendered, musically, with a grandeur, a momentum, a warmth, and at the same time a firmness and sureness of hand which would do honour to a great master.

19. Scène du combat: Taisez-vous !

Scarcely are they reunited than the Spanish burst into the Hôtel de Ville, at their head the Duke of Alba in the grand costume of a generalissimo.

Rysor and Karloo declare themselves leaders of the revolt;they learn that a woman has denounced them. Fortunately, the Duke of Alba has not asked her the signal for the revolt.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Superiorly treated. Made of almost nothing: a few drums and bugles, calls outside, and orchestral responses, it is an irresistible progressionof rhythm and sound.

- Gazette artistique de Nantes (Wilder): The arrival of the Spaniards to the veiled sound of the drums, beating the charge far off; the effect is both seizing and sinister.

- Le monde illustré (Boisard): One of the most striking pages … with its tumult mixed with detonations and drum rolls.

20. Scène du sonneur: Messieurs ! quel est celui ?

They beg Jonas not to give the signal; the poor bell-ringer says: “I have a wife and child”; he goes up to the belfry; there is a moment of anguish; finally, they hear the funeral knell: the warning signal to William of Orange.

Jonas has not weakened. On these funereal notes, Karloo throws an apostrophe of triumph. Kill that man! shouts the Duke of Alba; and Jonas is shot near his bells.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Really this fourth act is complete. Here is the scene of the ringer and the call of all the Flemings to the heroism of one. Their plea is heartbreaking, especially when the unison of the choral masses weighs heavily on poor Jonas’s weakness. While awaiting the signal, under the threats of the Duke of Alba, a single prayer bursts forth from a thousand hearts, so spontaneous and so ardent, that there is no longer any concern here about reminiscences. We do not remember our memories anymore; the breath of this inspiration has carried them all away.

21. Final: Mon père ! pas pour tous

Rafaële reappears, and asks for Karloo’s pardon; she loves him !

Karloo wants to refuse, but Rysoor puts a dagger in his hand, giving him the mission to kill, whoever she is, the woman who betrayed them.

The murderers bring on the corpse of the savior of the country. Then the martyrs of the next hour kneel before the martyr of the first hour, and Rysoor, in the name of all, salutes him, and thanks him.

Pauvre matyr obscur…

La légende apprendra ton nom à nos enfants,

Ils garderont toujours ta mémoire bénie.

The aria has been recorded by Henri Stamler, Pierre d’Assy (1908), Jean-Francisque Delmas (1904 and 1908), Louis Nucelly, Titta Ruffo (1920), Paul Lantéri (1929), Jean Claverie (1930/1931), George London, and Joseph Shore (1974).

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Admirable serenity, as close to genius as the enthusiasm of a moment ago. Decidedly, we remain on the summits, and, after an act of this magnitude, M. Paladilhe has, like his heroes, well deserved of his country.

- Le Ménestrel (Pougin): This song of sorrow and regret is one of the musician’s most beautiful, noble, touching inspirations.

ACTE V

22. Récit et air: L’échafaud, le bûcher ! (Dolorès)

Dolorès, who thinks only of her lover, wants to flee with him.

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): Infinitely charming; but it is perhaps not to the stature of the character, this ferocious soul, who must love, as she hates, disproportionately.

- Le monde illustré (Boisard): Without conviction or warmth

23. Duo: Ah ! Madame ! parle ? (Dolorès, Karloo)

24. Scène finale: Fuyons! Fuyons!

Karloo is on the point of yielding to this temptress; but no, he swore on his eternal salvation, he swore to kill the woman who denounced the leaders of the revolt. She betrays herself. In vain, she implores forgiveness.

He stabs her, and goes to join his companions in arms and friends, to die with them

- L’année musicale (Bellaigue): The final duo singularly grows Karloo. The first recits of the young man say with gravity his repentance and his resolution. But, to his farewell, Dolorès replies with a provocation of love, and to reconquer him one phrase, exquisite and original, suffices: Viens, nos maux sont finis, mon cher amour, ah ! viens, je t’aime ! A roll of drums announces the arrival of the condemned; the priests sing the office of the dead. Nearly all the scene is built on the Dies irae alternately chanted in the wings and paraphrased by the orchestra; here is a real find. Above the distant noises, in this deserted house, the duo takes on an astonishing shape. The declamation is vibrant and full of lightning; it stabs like invective, especially at Karloo’s phrase: Je frapperai l’auteur de ce forfait,which begins a thundering crescendo. The peroration is still more striking and traversed by Dolorès’ appeal to her lover’s pity. After the Dies irae follows a beautiful song of the heroes marching to execution. Karloo at first throws his imprecations into the middle of the stoic hymn; but soon he sings it, and, in a hallucination of patriotism, kills and dies. This duet is one of the greatest pages of the score; to finish thus is to finish gloriously.

25. Scène: Ah ! mon Dieu ! le pardon !

In rehearsals, the opera ended with Karloo leading Dolorès to the foot of the funeral pyre which Rysoor and his companions have just climbed; he stabs her, and then joins his companions. This was found too brutal, and was dropped.

Bibliography

Camille Bellaigue, L’Année musicale (October 1886)

Le Petit journal (18 December 1886)

Victor Wilder, Gazette artistique de Nantes (23 December 1886)

A. Boisard, Le Monde illustré (25 December 1886)

Albert Dayrolles, Les Annales politiques et littéraires (26 December 1886)

Arthur Pougin, Le Ménestrel (26 December 1886)

Edouard Durrand, La Justice (27 December 1886)

Le Costume au théâtre et à la ville (1 January 1887)

L’Universelle exposition de 1889 illustrée (1 February 1887)

Daniel d’Arthez, L’Ouest-artiste – gazette artistique deNantes (23 December 1893)

Ascanio, Le Monde artiste (17 February 1895)

Les Spectacles (22 January 1926)

Etienne Gervais, Bulletin mensuel de l’Académie des sciences et lettres de Montpellier (1926)

Journal officiel de la République française (6 December 1926)

Noël Boyer, L’Action française (4 July 1944)

Vincent Giroud, French Opera: A Short History, Yale University Press, 2010

Steven Huebner, “After 1850 at the Paris Opéra: institution and repertory”, The Cambridge Guide to Grand Opera, Cambridge University Press, 2003

David Le Marrec, “Patrie! – Le portrait inversé de Don Carlos”, Carnets sur Sol, 19 April 2010

What an amazing little bit of historical reconstruction, and on a work that very well deserves it! This gives me some ideas as I work on revisions for my own thesis which involves historical reconstruction. Also, this is probably the next best thing to actually hearing the complete performance of the last grand opera!

LikeLike

Thanks, Phil! I’m uploading a gallery of costume designs as we speak.

LikeLike

I can tell that you really don’t like Dolores, that probably isn’t bad seeing her own lover executes her.

LikeLike

The synopsis is based pretty heavily on Le petit journal! She’s another one of French opera’s bad girls.

LikeLike

I notice similarities to both Les Huguenots and Le duc d’Albe/Les vepres siciliennes (the fifth act seems to parallel the fourth act of Huguenots) in the plot and of course the references to Guillaume Tell from the critics of the period are glaring.

I wonder, will it ever see the light of day? Complete I mean?

LikeLike

Yeah, the fifth act is a lot like the Huguenots love duet. Where do you see the Vêpres parallel?

LikeLike

In connection to Le duc d’Albe more than the Sicilian setting, act 3 is basically act 3 scene 1 of Vepres, even starts off with a bass/baritone aria, then a conspiracy is revealed. The religious persecution element is another similarity with Huguenots and Don Carlos.

The Duke of Alba shows up in far too many operas, at least to me. Oddly never as the main character! One would think that the opening of the dykes of Leiden and the ensuing flood of the countryside would make for good opera, tack on a love story of course. Instead, we end up with this odd tale of an illegitimate son by a Sicilian or Dutch woman in love with a Sicilian or Dutch woman bent on political revenge for the execution of one of her family members by the Duke, and not much actually about the Duke himself.

Here in Patrie! we have an adulterous relationship which is apparently atoned by the deaths of both partners. I’ve always found this rather common operatic concept of redemption through death to be so fascinating, even more interestingly when the characters are supposed to be Calvinists who would at least in theory not believe in free will. By the way, is any motivation given for the affair, I didn’t notice any mention of it?

LikeLike

Does love need motivation? On Dolorès’ part, it’s fairly clear she feels neglected by her husband; since his country’s liberty is more important than her, she feels, she looks for solace in the arms of his best friend. And she’s also an attractive woman.

Good point about Vêpres Act III! But isn’t this a fairly common structure in opera?

LikeLike

I guess, but it is the same genre at least.

I wonder if we are really talking about love or lust, though the two are usually blurred in opera. I would say that in theatre love/sex/romance does need a motivation even if it is a stupid motive. How much of a friend to Rysoor is Karloo if he is sleeping with his wife? He does redeem himself by killing her, but what would motivate someone to betray their friend in that way, especially without him figuring out how horrible Dolores is and losing all respect for her even before he kills her? Unless of course if the guilty secret now ties him to her. Yet again, isn’t Rysoor cheating on her with his patriotism and his neglect of Dolores?

Meanwhile, Rafaele seems like a very interesting secondary character. I think I would have liked more of her!

WOW! A LOT OF COSTUME DESIGNS! I think it doubled the size of the post!

LikeLike

I’d love to hear or see this; the plot sounds very dramatic, and (influence of Meyerbeer & Gounod aside) the critics admired the music. One for Bru Zane to do?

LikeLike

Was there any indication of how long it is? Is it one of those 2.5-3 hour grand operas or one of those 4 hour grand operas?

LikeLike

The scores are about 200 to 200 pages; I’d guess around the 3 hour mark.

LikeLike

That should read 200 to 250 pages!

LikeLike

any hint of a possible production?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish!

LikeLiked by 1 person

“What’s that to you, kid?” (said the composer of Les Troyens, doing his best Jimmy Cagney impression)…

Actually I read somewhere that Jimmy Cagney started modeling his movie voice after Berlioz’s voice when he met him once while working as a bar-back at a Parisian salon back in the day.

Or maybe he said after he hooked up with Berlioz in a Parisian bathhouse.

LikeLiked by 1 person