- Tragédie lyrique in prologue and 5 acts

- Composer : Jean-Baptiste Lully

- Libretto : Philippe Quinault, after Torquato Tasso

- First performed : Académie royale de musique, théâtre du Palais-Royal, Paris, 15 February 1686

Prologue

| LA GLOIRE | Soprano | |

| LA SAGESSE | soprano |

Tragédie

| ARMIDE, magician, niece of Hidraot | Soprano | Marie Le Rochois |

| RENAUD, a knight | Haute-contre | Louis Gaulard Dumesny |

| PHÉNICE, a confidante of Armide | Soprano | Marie-Louise Desmatins |

| SIDONIE, a confidante of Armide | Soprano | Françoise Fanchon Moreau, la Cadette |

| HIDRAOT, magician, King of Damascus | Basse-taille (bass-baritone) | Jean Dun père |

| ARONTE, guard of Armide’s captive knights | Basse-taille | |

| ARTÉMIDOR, a knight | Taille (baritenor) | |

| LA HAINE [Hatred] | Taille | M. Frère |

| UBALDE, a knight | Basse-taille | |

| The Danish Knight, a companion of Ubalde | Haute-contre | |

| A Demon in the form of a Water Nymph | Soprano | |

| A Demon in the form of Lucinde, the Danish Knight’s beloved | Soprano | |

| A Demon in the form of Melisse, Ubalde’s beloved | Soprano | |

| Heroes who follow Glory; nymphs who follow Wisdom; people of Damascus; demons disguised as nymphs, shepherds and shepherdesses; flying demons disguised as Zephyrs; followers of Hatred, the Furies, Cruelty, Vengeance, Rage, etc.; demons disguised as rustics; Pleasures; demons disguised as happy lovers | Chorus |

Armide, Lully and Quinault’s final tragédie lyrique, is generally considered their masterpiece. The critics, for once, are right. If you listen to only one Lully, listen to this.

Everything comes together here, in an erotic tale of a romance between a sorceress and a crusader.

It’s dramatically tight: a mere two hours, not counting the prologue. It’s psychologically interesting; while Armide is the familiar enchantress in love with the hero, she’s a human being rather than a villainess. The opera belongs to her, and we see her struggle between desire and hatred.

It’s ambiguous, too. Its overt message (like Roland’s) is that love is a bad thing, choose glory; “Ce que l’amour a de charmant n’est qu’une illusion qui ne laisse après elle qu’une honte éternelle,” sing the knights in Act IV. It’s refreshing to see an opera which, for once, doesn’t celebrate emotion; “Des charmes les plus forts la raison me degage”. (Love, of course, is a temporary insanity caused by a chemical imbalance.) But the opera ends with the distraught, abandoned Armide. True, Rénaud never loved her; he was under her spell – but her grief is still genuine.

It’s also perhaps Lully’s most melodic opera. While in earlier works the arias are heightened recits, here the recit itself is closer to arias, and the arias are more developed.

Act II has a dazzling series of numbers: the duet “Esprits de haine et de rage”; and Rénaud’s breath-takingly lovely sleep scene, with the nymph’s aria and chorus of heroic shepherd/esses.

The act ends with Lully’s most famous monologue, “Enfin il est en ma puissance”. Le Cerf de la Viéville said he saw audiences seized with fear, not breathing, rigid, their heart in their mouths … then breathing with a murmur of joy and admiration. Rousseau, however, thought the music failed to capture Armide’s emotional turmoil.

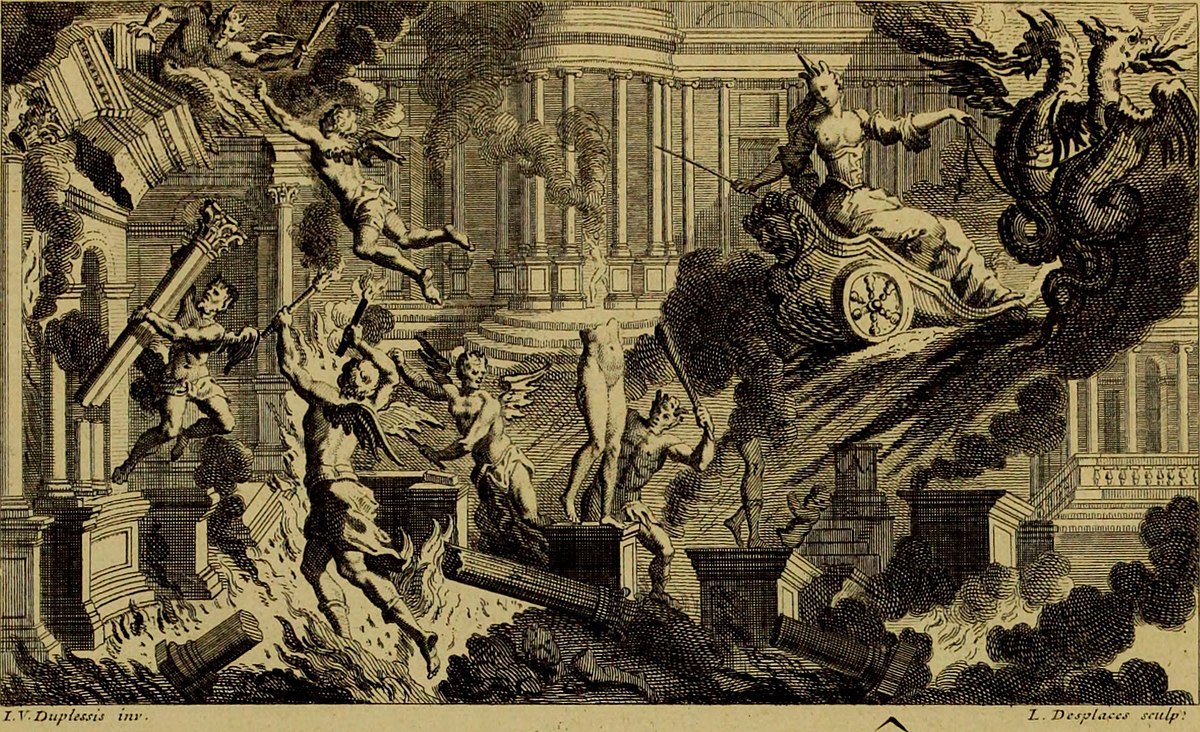

Act III has Armide’s celebrated invocation “Venez, venez, Haine implacable”, summoning Hatred and her entourage from Hell, and la Haine’s aria with chorus.

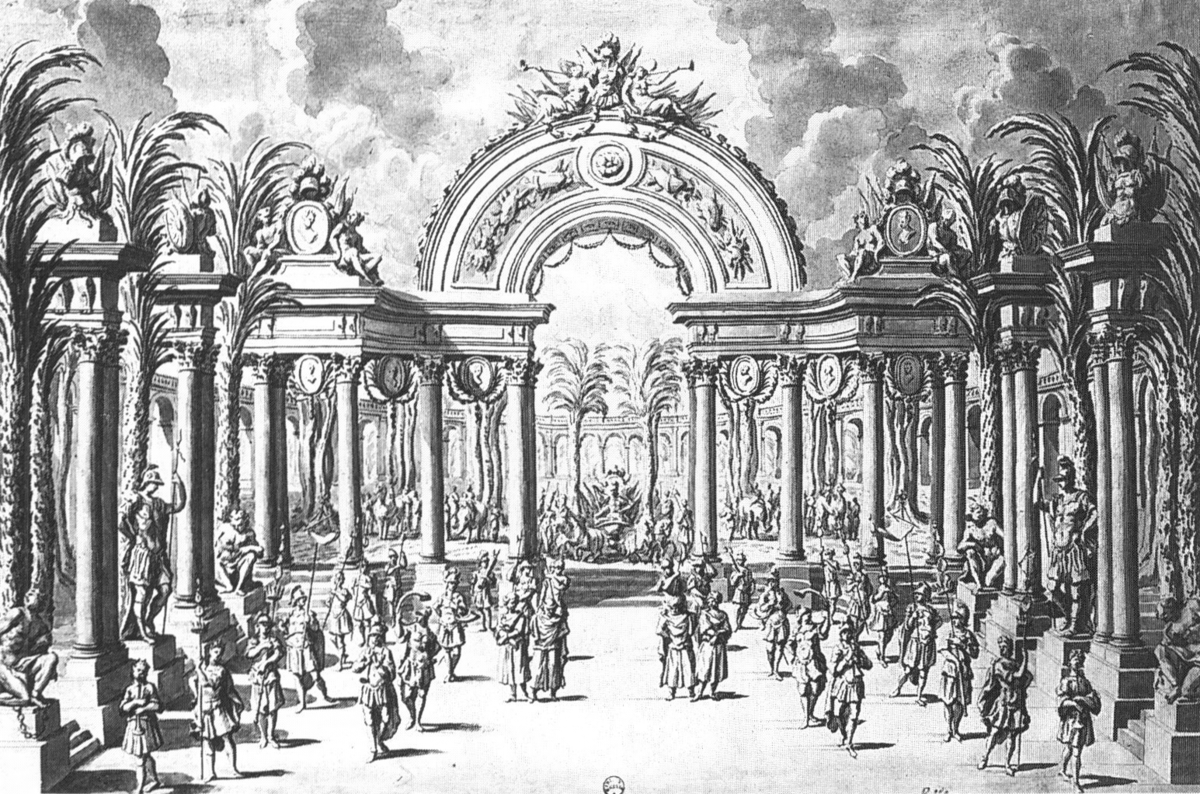

Act IV was traditionally cut; it’s a 15-minute divertissement, with the minor characters of Ubalde and the Danish knight. Clément complained it slowed the action, yielding place to dance and mise-en-scène, but it has a lively patter duet and some charming pastoral music – proof, Kaminski argued, that Lully hadn’t lost his sense of humour.

Armide’s powerful monologue “Le perfide Rénaud me fuit” ends the opera, before demons destroy her magic palace, and she flees in a flying chariot. “Nothing,” Laurencie wrote, “is more bitterly and desolately beautiful than Renaud’s farewell; nothing moving than the distress of the abandoned Armide.”

The first performance was coldly received. Lully’s “dissolute” (read: openly gay) lifestyle landed him in schtuck with Louis XIV, who had married Mme de Maintenon, and got religion. Lully’s valet / lover Brunet was forced to enter a religious order, and the king refused to attend a performance of the work, even though he had suggested the topic.

The court was absent from the first performance, and the public hardly dared to have an opinion on the work. Only the prologue, honouring Louis, was applauded.

The next day, Lully had the work performed for himself alone. The king concluded that because Lully found it good, it must be; and ordered another performance.

Court and public applauded – and Armide had a spectacular success. It was part of the French repertoire for 80 years, staged throughout Europe, and was the only Lully opera performed in Italy.

By 1762, however, audiences had cooled. “The work was remounted today without the least tumult. Popular enthusiasm for this beautiful opera has vanished like an enchantment. They find more music in the slightest opéra comique… This work can no longer hold its own before the opéra comique; the theatre is deserted when it advertises Lully’s masterpiece.”

Fifteen years later, GLUCK wrote his opera. His great work will be much more to modern tastes (it is, after all, by a genius) – but Lully’s Armide is a fine opera in its own right, and arguably its composer’s operatic masterpiece.

FURTHER READING

- Félix Clément, Dictionnaire des opéras, 1869.

- Piotr Kaminski, Mille et un opéras, Paris : Fayard, 2003

- Lionel de la Laurencie, Les maîtres de la musique: Lully, 2nd edition, Paris: Librairie Félix Alcan, 1919 (2nd edition)

- “Armide“, Opéra Baroque.

I recall we discussed Lully a while ago. Glad you liked it. SEEK OUT CROESUS BY KEISER.

LikeLike

Croesus duly sought out:

https://operascribe.com/2019/05/15/135-croesus-keiser/

LikeLike