- Comédie en 3 actes, mélée de morceaux en musique

- Composer: Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny

- Libretto: Michel-Jean Sedaine

- First performed: Opéra-Comique (Hôtel de Bourgogne), Paris, 22 November 1762

Le roi et le fermier has as much claim to be the first “modern” opera as Gluck’s Orfeo (also 1762). It’s arguably the first great, “easily accessible” French opera: full of tunes, cheer, striking sonic effects, and actual people. Rameau‘s Hippolyte et Aricie is magnificent, but it’s a historic artifact. With Monsigny’s opera, we step straight from the classical world of tragédie lyrique, with its gods, heroes, kings, and monsters, into an intimate, human world anticipating Weber’s Freischütz.

The 1760s and 1770s were, Giroud argued, the golden age of the opéra-comique. “Its vogue paralleled an evolution of the French theatre in general, away from the classical tragedy and its mythological or ancient themes, and towards what Diderot called the “drame bourgeois”: serious plays, usually in prose, set in the present, and involving characters with whom a middle-class audience could identify and situations it would recognise.”

And Monsigny – with Duni and Philidor – gave French audiences a pleasure yet unknown, Pougin wrote. “It was with a real joy, almost enthusiasm, that spectators applauded the qualities of grace, charm, tenderness, warm inspiration, which the musicians lavished on works of so new a character.” Similarly, Bellaigue hailed Monsigny, with Grétry, Dalayrac, and Nicolò as the first masters, the exquisite masters of the oldest French melody.

“Of all the composers of our country,” Paul Dukas wrote in 1883, “he is probably the first who had the gift of true, human emotion, of communicative expression and of the right feeling … The frail melodies of Monsigny are no doubt nothing more than melodies, but of such moving inspiration, of such sincere accent, of such natural and charming shape that one freely ignores their feeble harmonic support and one forgives this instinctive musician, who dreamt them up, his unaffected artistry, in favor of the pleasure that he provides us.”

Monsigny devoted himself to a musical career after seeing Pergolesi‘s Serva padrona in 1754. His early works, written for the Foire theatres, include Les aveux indiscrets (1759) and Le cadi dupé (1761). On hearing this work, the librettist Sedaine exclaimed: “Voilà mon homme!” Their first joint work was On ne s’avise jamais de tout, performed at Fontainebleau in 1770, then at the Foire St-Laurent in 1771. It was a favourite with Louis XV. We will discuss their masterpiece, Le déserteur (1769), next month.

Le roi et le fermier, Bauman claims, is ground-breaking. “It enlarged the dramatic weight of Rousseau’s opposition of healthy rustic innocence and corrupt courtly mores. In so doing, it revealed new powers of social and political criticism.”

The plot comes from Robert Dodsley’s The King and the Miller of Mansfield (1737), translated into French by one Patu. Charles V or Henry IV, according to tradition, spent a night lost in a forest after a hunt; he entered a woodcutter’s cottage; and there, for the first time, he saw what a man is to another man stripped by his ignorance of respect for his king.

“Never has a scene in the theatre opened to any poet a wider career, a simpler means of making useful truths heard,” Sedaine wrote in his preface.

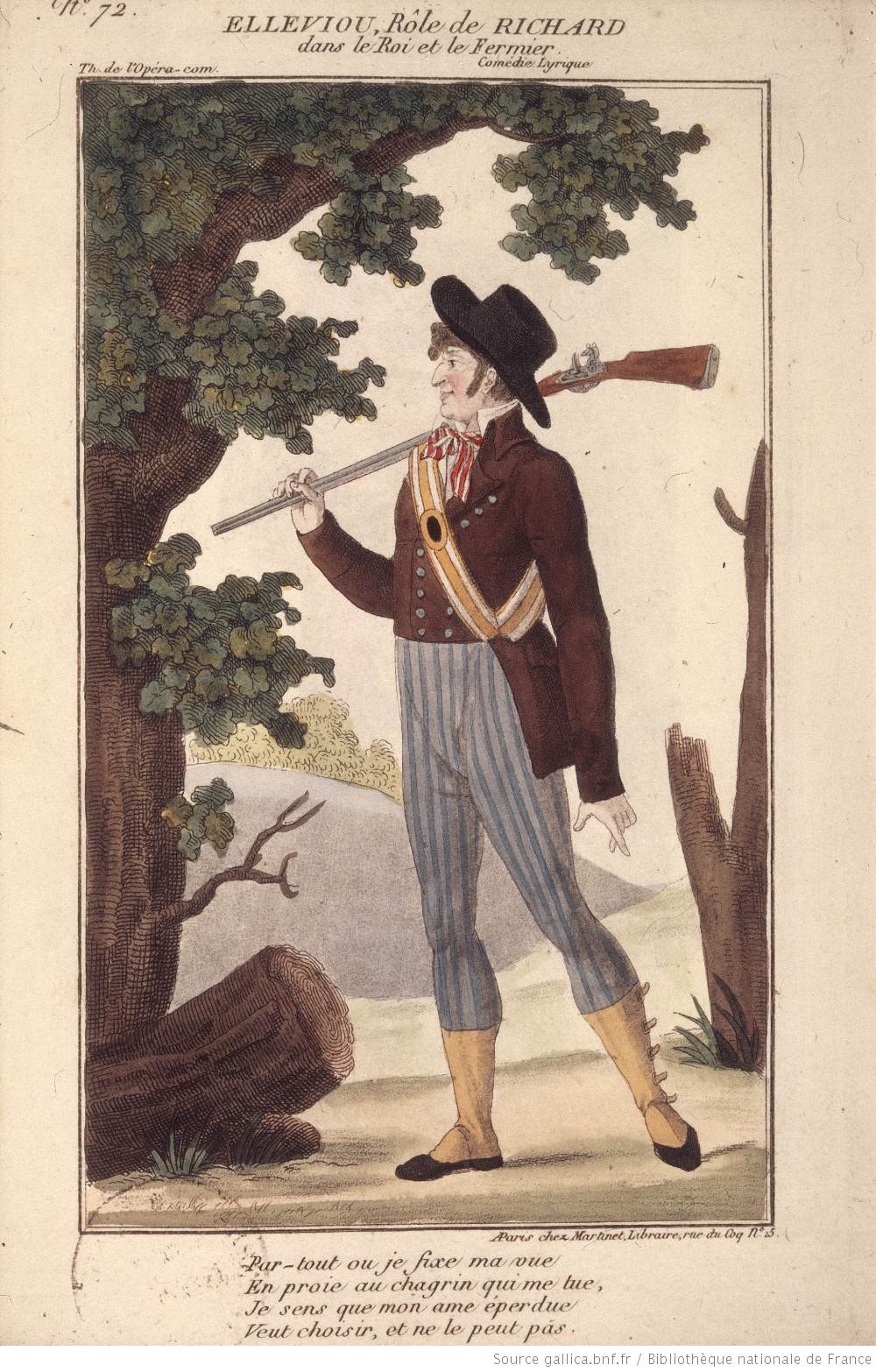

The action takes place in Sherwood Forest, several centuries after Robin Hood. The farmer, Richard, gamekeeper inspector of the forest, is beside himself with jealousy and worry (“Je ne sais à quoi me résoudre”); his fiancée, Jenny, entered the castle of “Milord”, a lustful despot aptly named Lurewell, and Richard fears the worst (“D’elle même, et sans effort”). Jenny escapes Milord’s clutches, shinning down the traditional set of knotted sheets; she reassures Richard that she didn’t suffer a fate worse than death, in an aria that could have been written by Boieldieu or Auber; and the couple are united. That’s the first act.

A storm breaks during the finale; storm clouds gather, strings growl, the wind howls, trees come crashing down; the king’s hunting party gallops by, blowing horns; shots ring out. (Weber must have had it in mind when he composed the Wolfsschlucht scene half a century later.)

Act II opens with a brace of gamekeepers, lost in the dark, singing a patter duo; it anticipates, in a way, Meyerbeer’s Pardon de Ploërmel. The king has been separated from his companions; in the bravura aria “Dans les combats”, he reflects that cannons and battles cannot daunt him, but the woods fill him with horror. Passing himself off as a mere courtier, he meets Richard, who invites him home for supper. Lurewell was also among the hunters, and he and a courtier are lost in forest. Unaware that Jenny has escaped, he looks forward to exercising his droit de seigneur (“Un fin chasseur”) – but Richard’s gamekeepers mistake them for poachers and arrest them, in a quartet finale.

The third act is cozily domestic; we are in the bosom of Richard’s family, with his kindly if distracted mother, and his sweet sister. As they spin and tat, the women sing three different arias, which Monsigny ingeniously combines.

The peasants entertain their guest, the mother somewhat embarrassed to serve a nobleman their simple rustic fare. This down-to-earth, human cheerfulness is like nothing we’ve seen in French opera before; when Rameau wrote comedy, it was either mythological (as in Platée) or exotic ballet (Indes galantes).

There’s even some pointed political commentary: that kings are surrounded by flatterers, and are never in a position to see men as they are. A far cry from “Hail Louis XIV, greatest monarch of the universe!” Richard claims that true happiness is only to be found in humble cottages (“Ce n’est ici, ce n’est qu’au village”), while the king maintains that the highest happiness for a royal is to make others happy (“Le bonheur est de le répandre”).

The king unmasks himself to punish Lurewell, launching a spirited confusion septet (“Le Roi, le Roi”). He banishes Lurewell, knights Richard, and give Jenny a dowry to marry him. A vaudeville finale closes the work, with the catchy refrain: « Il ne faut s’etonner du rien, il n’est qu’un pas du mal au bien ».

Monsigny and Sedaine dreamt of a more serious opéra comique than hitherto known, Pougin wrote, where, if emotion and sensibility were not always absent, public and authors alike looked above all for gaiety, even coarse buffoonery. Le roi et le fermier certainly didn’t lack comedy, but it was less frivolous, with a more developed plot and sustained interest than was customary.

“Never did good or bad work have so much trouble to appear in the theatre,” Sedaine wrote. “I had to find a great artist, a skillful musician, with confidence in me; a friend who wanted to risk a new genre in music; and however rare poets are in this new genre, musicians are even more so.”

The newness of the subject unsettled audiences; they greeted it at first with reserve, even coldness. The Mercure, not wanting to commit itself, merely announced the work’s appearance on the boards, leaving a detailed account until its success or failure had been decided.

“At the first performance, this piece, in the modern genre of intermèdes, although applauded, appeared to be of doubtful success. Several pieces of music were, nevertheless, applauded. The public seemed to demand some cuts; these have been made; and the performances continue with a sufficient number of spectators. We shall speak in more detail of this novelty, and with more certainty as to its fate in the next Mercure.”

Enthusiasm soon followed caution, and the work was performed more than 200 times, bringing more than 20,000 francs to the composer and librettist. “The composer deserves his praise,” the Mercure wrote in its second article, “not only for the beautiful, ingenious, and reasoned images in his symphonies [Pougin thought this referred to the storm entr’acte] but for the sagacity with which he found a way to make singing speak, and to make it speak without confusion in its ensembles.”

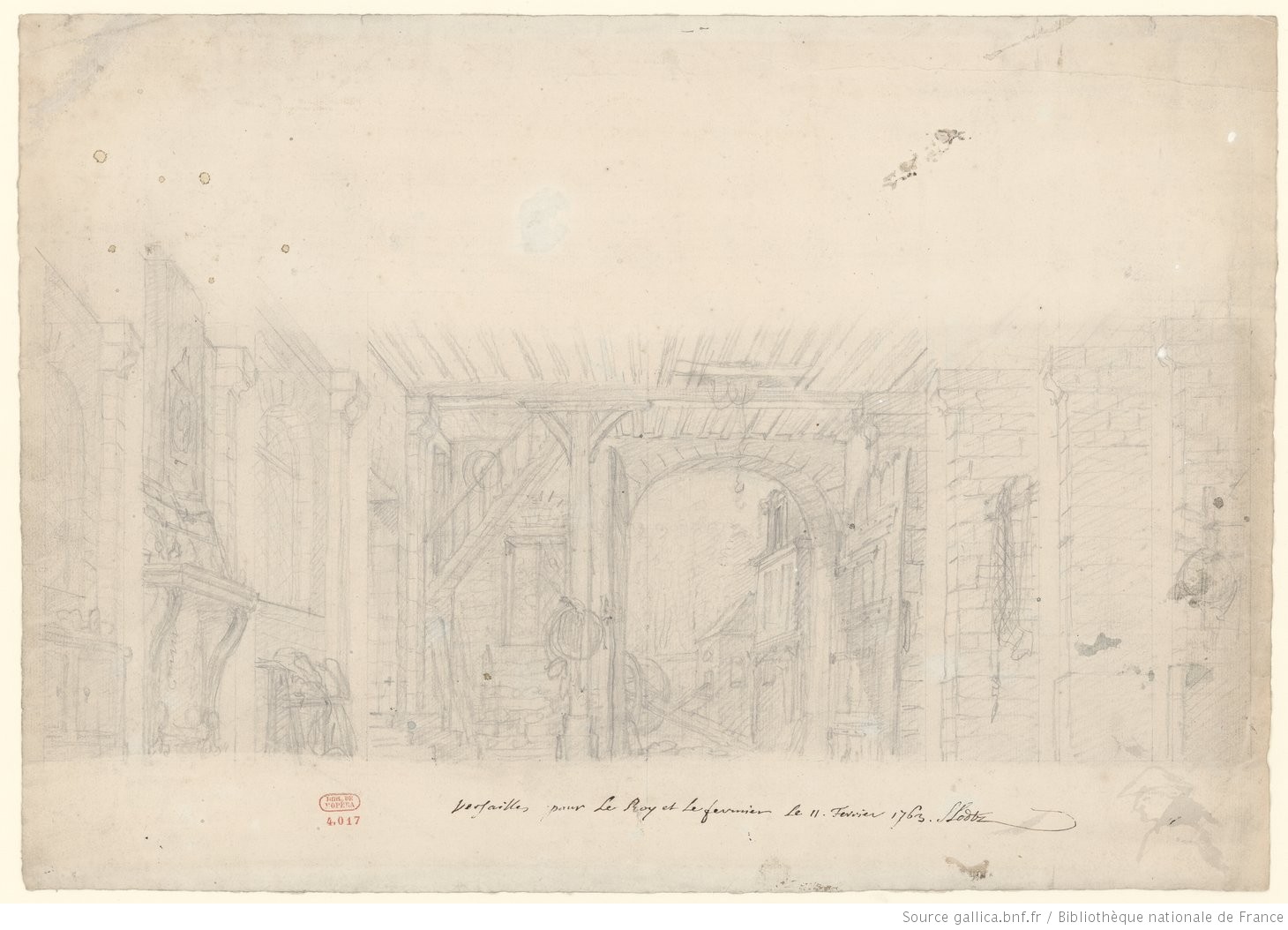

The work soon reached Vienna (“Never has an opéra comique met greater success in this country”) and St Petersburg. Marie Antoinette sang the role of Jenny on her private stage in the 1780s. (The sets somehow survived the Revolution, and were used at Opera Lafayette’s production this decade.) The work seems to have last been performed in France in 1806.

Nineteenth-century critics found it naïve, but admirable. It is never boring, Pougin thought; it offers a truly theatrical subject, which excites the sympathies, and engages the audience throughout. Clément thought the work might suffer from meagre and even defective harmony and clumsily written vocal phrases, but it was grippingly natural, truly sensitive, and even passionate. Monsigny may have less genius and invention than Grétry, but greater depth of feeling. With less art, he could move audiences more.

‘Who needs art?’ Scudo could have retorted. Monsigny may not have been a trained musician like Rameau or Philidor, but his lively sensibility and his natural instinct for melody allowed him to bypass a science that had not saved his two illustrious contemporaries’ works.

This should certainly re-enter the repertoire.

RECOMMENDED RECORDING

Thomas Michael Allen (Le Roi), William Sharp (Richard), Dominique Labelle (Jenny), Thomas Dolié (Rustaut), Jeffrey Thompson (Lurewel), Delores Ziegler (La Mère), Yulia Van Doren (Betsy), David Newman (Charlot), and Tony Boutté (Le Courtisan). Ryan Brown conducting Opera Lafayette Orchestra, Naxos, 2012.

WORKS CONSULTED

- Thomas Bauman, “The eighteenth century: Comic opera”, in The Oxford History of Opera, ed. Roger Parker, Oxford University Press, 1996

- Camille Bellaigue, “Un Siècle de musique français – l’Opéra-comique”, Revue des Deux Mondes, 1886

- Félix Clément, Dictionnaire des opéras, 1869

- Vincent Giroud, French Opera: A Short History, Yale University Press, 2010

- Piotr Kaminski, Mille et un opéras, Paris : Fayard, 2003

- Nizam Kettaneh, « Le roi et le fermier », Naxos

- Arthur Pougin, Monsigny et son temps: L’opéra-comique et l’opéra italienne: Les auteurs, les compositeurs, les chanteurs, Paris: Librairie Fischbacher, 1908

- Pierre Scudo, https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Revue_musicale,_1862/03 – Pierre Scudo

I’m absolutely clueless about opera comique, is this a good place to start? What are the must play before you die opera comiques?

LikeLike

Carmen, of course; Delibes’ Lakme; Boieldieu’s Dame Blanche; Auber’s Fra Diavolo and Cheval de Bronze (maybe le Domino noir, too); Gretry’s Richard, Coeur-de-lion; Herold’s Pre aux clercs; Meyerbeer’s Etoile du nord and Dinorah.

Many Massenets premiered at the Opera-Comique, but Manon, Werther, Esclarmonde, Cendrillon, and Griselidis aren’t opera comiques in the traditional sense. Even less so are Debussy’s Pelleas and Dukas’s Ariane!

LikeLike

I have a confession to make which I’m not proud of: I think Carmen is the most overrated opera ever composed….Anyway… I’ve always been somewhat confused by the term opera comique how is something like Werther a comedy? Am I missing something , is it something to do with spoken dialogue?

LikeLike

No, “comique” doesn’t mean “comic”! Opera comique was originally a spoken play with sung numbers, like a 20th century musical. (Opera was sung from start to finish.) They were premiered at the Opera-Comique theatre – where operas were created long after the original opera comique form had disappeared. All rather confusing, really.

I have mixed feelings about Carmen. Partly to do with having the tunes go through my head while feverish with gastroenteritis.

LikeLike

Okay, thanks for clearing that up.

I don’t like Carmen because it’s completely overshadowed so many great french operas of the period like Le roi d’Ys, Henry VIII, Cendrillon etc. Gets my goat that they’re not more popular, Carmens fault I’m sure.

LikeLike

There’s a lot of marvellous French operas which are sadly obscure. Like Reyer’s opera comique La statue! As successful as Gounod’s Faust; performed for two years. Bizet thought it the most remarkable work written in France for twenty or thirty years. Massenet, who played the timpani in the orchestra, called it a superb score. Berlioz and, decades later, Bruneau praised it. Not a single recording, nary a production in a century.

And don’t get me started on Halevy!

LikeLike