- Opera seria in 3 acts

- Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Libretto: Vittorio Amedeo Cigna-Santi, based on Giuseppe Parini’s Italian translation of Racine’s Mithridate

- First performed: Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan, 26 December 1770

| ARBATE, Governor of Nymphæa | Soprano castrato | Pietro Muschietti |

| SIFARE [Xiphares], son of Mitridate and Stratonica, in love with Aspasia | Soprano castrato | Pietro Benedetti (Sartorino) |

| ASPASIA, betrothed to Mitridate and already proclaimed queen | Soprano | Antonia Bernasconi |

| FARNACE [Pharnaces], elder son of Mitridate, also in love with Aspasia | Alto castrato | Giuseppe Cicognani |

| MARZIO [Marcus], Roman Tribune, friend of Farnace | Tenor | Gasparo Bassano |

| MITRIDATE, King of Pontus | Tenor | Guglielmo d’Ettore |

| ISMENE, daughter of the Parthian King, in love with Sifare | Soprano | Anna Francesca Varese |

SETTING: Around the Crimean port of Nymphæum; 63 B.C., during the conflict between Rome and Pontus

Mitridate, re di Ponto was Mozart’s first important opera: commissioned to open the Milan season, apparently on Hasse‘s recommendation. The libretto was based on a 1673 play by Racine, and had previously been set by one Quirino Gasparini in Turin in 1767.

Despite a difficult rehearsal period and demanding singers, Mitridate was a triumph. “Evviva il maestro!” shouted the Milanese, who saw the opera 21 more times, not fazed by its six-hour running time (including an interpolated ballet).

Giuseppe Parini, the Italian translator of Racine, praised Mozart for having studied beauty in nature, and expressed human passions in a vital and lively manner.

Mitridate then slumbered for two centuries, not revived until 1971, in Salzburg. Some claim that it is Mozart’s first masterpiece; some even claim that it is a better opera seria than Idomeneo or La clemenza di Tito. Other critics – Einstein and Dent among them – think an opera seria based on Racine was beyond the teenager’s powers.

Certainly, nobody should judge opera seria – at its height, a form of great beauty, power, and exhilarating vocal virtuosity – from Mozart’s attempt.

Opera seria, you will remember, is a historical (generally Classical, occasionally mediaeval) story; the action progresses through secco recitative, while arias provide breathing spaces where characters emote – and, of course, SING. These arias were displays of vocal virtuosity for the star singers (mainly castrati) of the day. Think of the insane acrobatics of Rossini – then multiply tenfold.

This for me is one of the golden ages of opera. The best works of the type – Vinci‘s Artaserse and Catone in Utica; Porpora‘s Germanico in Germania; Vivaldi‘s Orlando furioso and Farnace, for instance – rank with the masterpieces of opera from any period.

Then there are the rapturously beautiful or thrilling arias performed by Franco Fagioli, Max Emanuel Cencic, Philippe Jaroussky, and Cecilia Bartoli. This is also the age that produced the greatest aria of all time: the wonderfully flamboyant “Vo solcando un mar crudele”. I listen to it every day.

Over the last few months, I have, like the young Meyerbeer, wandered “bewitched in a magic garden”.

Mitridate, though, is a work of decadence. Opera seria was sixty years old, and had changed little in that time; the careful, elaborate plot construction and strong characterisation of Metastasio, master of the libretto, had degenerated into convention, rhetoric, types, and tropes.

The plot is almost opera seria-by-numbers: an Ancient World, Near East court; a tyrant; half-siblings, one good, one bad, who are rivals in love (a trope that goes back at least to Vivaldi); the jilted mistress of one of them; and a few battles to spice up the action. Surprisingly, it doesn’t have a woman disguised as a man (or, better, a man playing a woman disguised as a man).

Mitridate exists in a different temporal dimension; like the event horizon of a black hole, it slows down time. Some of the individual numbers (three, perhaps five, out of 23) are wonderful, but the opera as a whole exerts a powerful tedium. There is almost no action, characterisation … or inspiration.

Like a lot of opera seria, Mitridate combines family drama with politics. Mithridates VI, king of Pontus (in modern Turkey), is at war with Rome; he spreads rumours of his death in battle with Pompey the Great to discover if either of his sons are in love with his fiancée Aspasia. Both do, but she only loves his younger son, Sifare. (Everyone hates Farnace.) Mitridate tries to kill his bride and sons; they survive; he kills himself instead.

ACT I

Town square of Ninfea

Hearing of his father’s death, Farnace tries to seize both the throne and his father’s bride. Aspasia asks for Sifare’s protection against Farnace (“Al destin, che la minaccia”: a brilliant virtuoso aria). Sifare declares that he can suffer Aspasia’s coolness without offence, but his brother is his rival (“Soffre il mio cor con pace”).

Temple of Venus

Farnace tries to force Aspasia to marry him; Sifare prevents him. Arbate, the town’s governor, tells them that Mithridates has survived, and is on his way, and urges peace between the brothers (“L’odio nel cor frenate”). Aspasia goes off to weep (“Nel sen mi palpita dolente il core”). Farnace suggests that the brothers stop Mitridate from entering the city; the faithful Sifare refuses, but will at least keep their mutual love for Aspasia secret (“Parto: Nel gran cimento”). Farnace conspires with his Roman ally Marzio (“Venga pur, minacca e frema”: dull).

Seaport

Mitridate arrives with Ismene, formerly betrothed to Farnace. Pompey defeated the king on the battlefield; he does not return victorious, but at least he has not been disgraced (“Se di lauri il crine adorno”). He has brought Ismene to marry his son – but she suspects he doesn’t love her (“In faccia all’ oggetto”: pleasant but forgettable). Mitridate learns that Farnace, believing his father dead, offered throne and marriage to Aspasia, but is relieved to hear that the dutiful Sifare has shown no signs of love for Aspasia. He vows vengeance on Farnace in the thrilling “Quel ribello e quell’ingrato”.

ACT II

Royal apartments

Ismene learns that Farnace no longer loves her; she threatens to go to Mitridate – but he warns her she could regret her revenge (“Va, l’error mia palesa”: short, uninteresting). Mitridate tells her Farnace will die; why not marry Siface? The king shares his suspicion that Aspasia is Farnace’s lover with Siface; he orders him to remind her of her duty, and warns her to beware his anger (“Tu che fedel mi sei”). Aspasia reveals to Sifare that she loves him, but orders him to be gone (honour before love). Sifare bids her farewell (“Lungi da te, mio bene”: long, slow, notable only for horn obbligato). Aspasia tries to forget Siface, but is caught between love and duty. “Nel grave tormento” is the best aria in the opera. Peace returns to her heart in a dreamlike adagio; but a frenetic allegro (complete with staccato runs) reveals her true feelings.

Mitridate’s camp

The king suspects Farnace of treachery (siding with the Romans). He announces he will avenge his defeat by marching on the Capitol itself; Farnace, as Ismene’s husband, will march with him. The Roman envoy Marzio arrives with an offer of peace. Learning that he arrived with Farnace, Mitridate arrests his son.

Ismene implores the king to be calm (“Se quanto a te dispiace”: florid, with seven bars of vocalises on the word ‘pace’). Farnace admits his guilt, but reveals that Sifare loves Aspasia too (“Son reo; l’error confesso”).

Mitridate tricks Aspasia into revealing her love for Siface. The tyrant imprisons both his sons. Before marching on Rome, he will ‘exact a notorious revenge through the slaughter of his sons and of his bride’ (“Già di pieta mi spoglio”).

Aspasia asks Sifare to kill her, to forestall Mitridate’s vengeance. He instead advises her to please Mitridate, swear eternal devotion to him, ascend the throne, and let Sifare’s cruel fate cost her nothing but tears. The two resolve to die together (duet: “Se viver non degg’io”).

ACT III

The hanging gardens

Ismene has tried to hang herself; she begs for mercy for Aspasia from Mitridate (“Tu sai per chi m’accese”: boring). Mitridate offers marriage to Aspasia in exchange for Sifare’s life; she refuses. The Roman army attacks the city walls. Mitridate prepares for battle; he goes to meet his fate – but Aspasia will precede him in death (“Vado incontro al fato estremo”: energetic, lots of high notes). Mitridate’s Moorish servant gives Aspasia a cup of poison to drink; she prepares to commit suicide (“Pallid’ombre, che scorgete”: plodding, lugubrious). Sifare (rescued by Ismene) stops her in time, and goes off to fight next to his father (“Se il rigor d’ingrata sorte”: uninspired).

The interior of a tower adjoining the walls of Nymphaea

Farnace is in chains; Marzio and the Romans free him. They will put him on the throne once Mitridate is defeated (“Se di regnar sei vago“: unremarkable; the young Juan Diego Florez sings this as a cameo in Rousset’s 1999 recording). Farnace instead repents; led by reason, not emotion, he will retrace the path of honour (“Già degli’occhi il velo è tolto”: WAY overlong at 9 1/2 minutes).

A ground-floor hall adjoining a grand courtyard in the Palace of Nymphaea

Mitridate is victorious – the Roman fleet burns in the background – but mortally wounded. Guards carry the king, dying, in on a litter. He has stabbed himself rather than surrender to the Romans. Suddenly, the tyrant becomes a magnanimous, loving father, reunited with the three people he tried to kill. (Eighteenth-century opera!) He dies; and his family vow to resist Rome (quintet: “Non si ceda al Campidoglio”: perfunctory, as Charles Osborne remarked).

Mozart was 14 when he wrote Mitridate, on the cusp of adolescence, beginning the struggle that would make him a man or a mousse. And what did he choose for his theme?

A tyrannical father who wants to kill his son; who is jealous of his sons’ burgeoning sexual prowess; who takes away his son’s swords.

Voici Leopold Mozart.

There are two sons: the “good” Sifare (dutiful, loyal; the son Mozart thinks he must be to please his father; the son his father wants him to be) and the “bad” Farnace (the disobedient son who wants his father’s position and his father’s woman, and who sides with his father’s enemy).

And the opera ends with the death of the father, succeeded – supplanted! – by his sons.

Aphasia (sic) is, of course, the step-mother: a safe way for Mozart to deal with his mother fixation. In a gloriously phallic image, she wants Sifare to run her breast through with his sword, before his father can. Gosh.

Unable to cope with these unsettling Oedipal urges, the five main characters try to kill themselves. The Thanatos urge!

SUGGESTED RECORDINGS

Listen to:

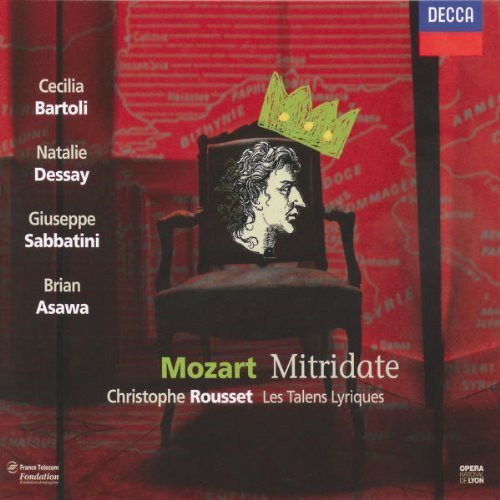

Cecilia Bartoli (Sifare), Natalie Dessay (Aspasia), Giuseppe Sabbatini (Mitridate), Brian Asawa (Farnace), with Christophe Rousset conducting Les Talens Lyriques, Decca, 1999.

Watch (?):

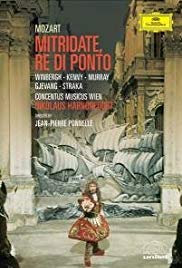

Gösta Winbergh (Mitridate), Yvonne Kenny (Aspasia), Ann Murray (Sifare), Anne Gjevang (Farnace), Peter Straka (Marzio), with Nikolaus Harnoncourt conducting Concentus Musicus Wien; directed by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, Vienna, 1986. Deutsche Grammophon.

Shot in the Teatro Olimpico, Vicenza, it’s beautiful to look at – but gad, it’s boring. I watched the bloody thing for three hours, yet the timer only crept up to an hour and a quarter. (Yes, I pinched that joke from Sam Clemens.) Worse, it seemed to make time run backwards. How could an epoch only last ten minutes? The sound quality isn’t great; the orchestra overshadows the voice; and it’s heavily cut, by an hour and a quarter. Six numbers are gone; so are the da capo passages; and the recit is slashed to ribbons. Swede Gösta Winbergh is excellent as Mitridate; so is Yvonne Kenny (one of Australia’s greatest sopranoes) as Aspasia.

WORKS CONSULTED

- Edward J. Dent, Mozart’s Operas: A Critical Study, 2nd edition, Oxford Univresity Press, 1947.

- Alfred Einstein, Mozart: His Character – His Work, trans. Arthur Mendel and Nathan Broder, London: Cassell, 1946.

- Klaus Oehl, “Mozart’s First Opera Seria”, Harnoncourt/Ponnelle DVD (Deutsche Grammophon), 1992/2006.

- Charles Osborne, The Complete Operas of Mozart, London: Victor Gollancz, 1978

Yay, your’e back! I never knew you held Vivaldi in such high regard, awesome *high five*

Shame, I can’t convince of George though…

LikeLike

Hurrah! 😉

I really enjoyed Serse (is it an opera seria?), and liked Arminio and Agrippina a lot. I’ll listen to the Minkowski Ariodante. What are the others you recommend, that I haven’t heard?

And what are your favourite Vivaldis?

LikeLike

Hmm let met see… Tito manilio, l Giustino, La fida ninfa, L’Olimpiade & Griselda from Vivaldi(and of course the ones you mentioned above)

Oh, definitely try the oratorio/opera hybrid Semele from good old George. There’s an exquisite recording with Kathleen Battle, too bad it’s not on period instruments but with singing like that I don’t care!

LikeLike

Ah yes, also Partenope(a nice light hearted work) almost on the same level Serse.

LikeLike

Also looking at your favourite operas I’m glad to see you’re a Glass fan to. You should try his Orphée if you haven’t already, it comes very close to the other two in inspiration IMO.

LikeLike

I’ll check it out – in a couple of centuries!

LikeLike