- Drame héroïque in 5 acts

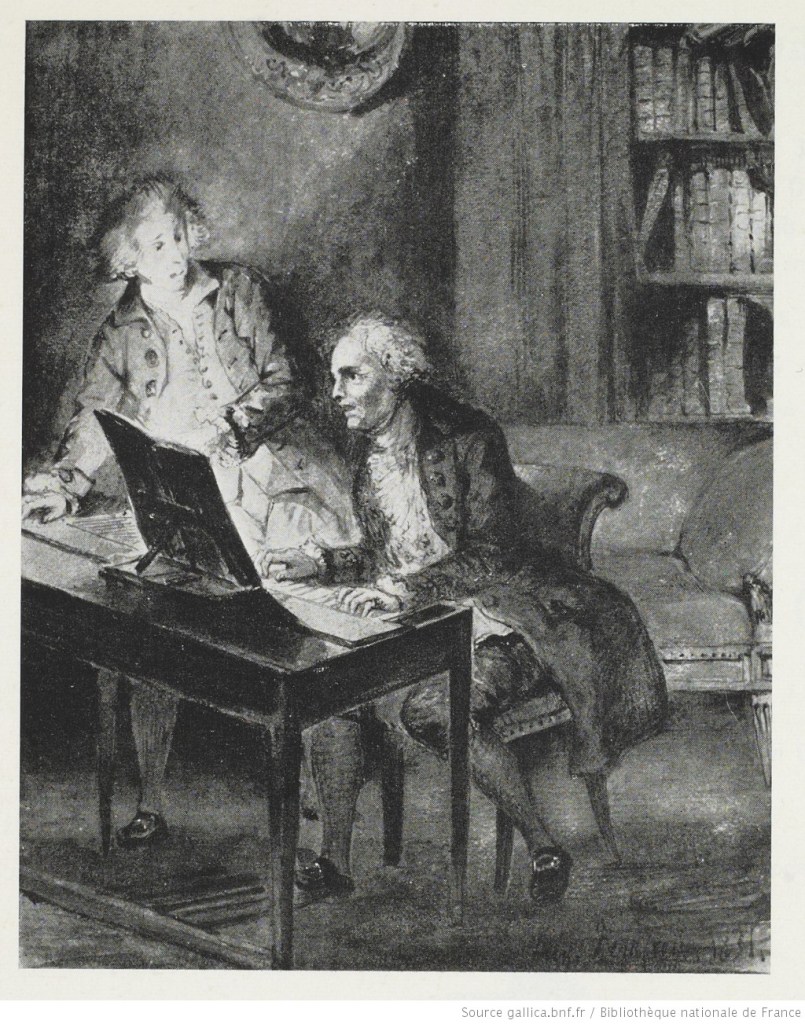

- Composer: Christoph Willibald Gluck

- Libretto: Philippe Quinault, after Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberate

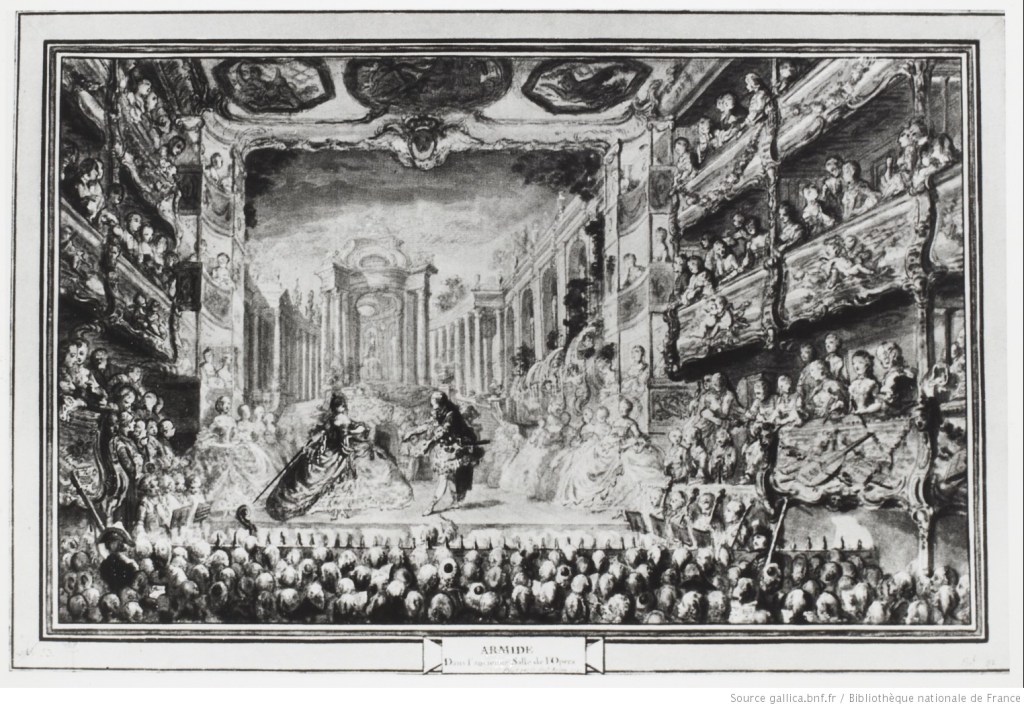

- First performed: Opéra (seconde Salle du Palais Royal), Paris, 23 September 1777

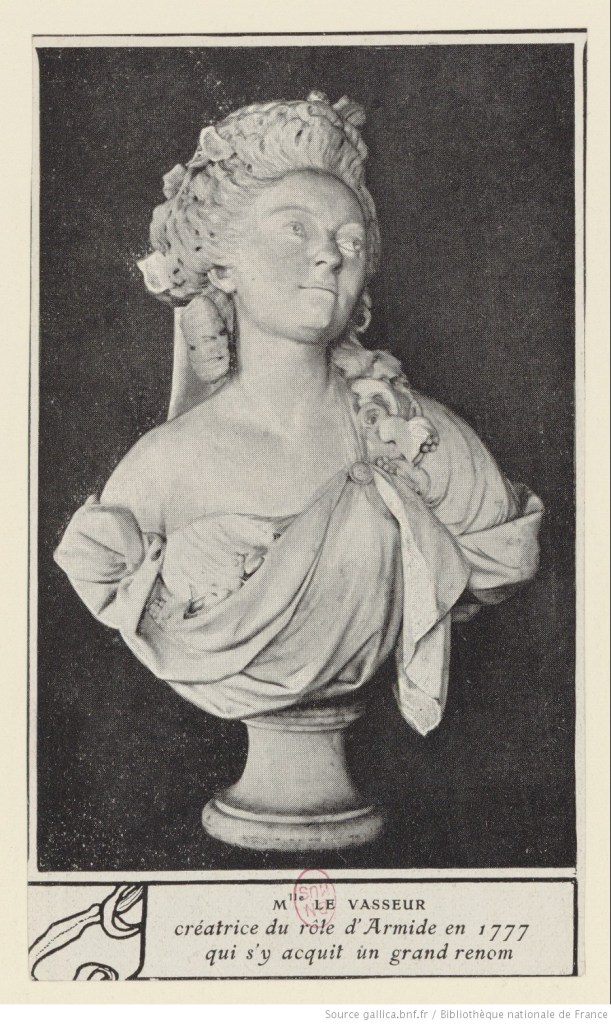

| ARMIDE, A sorceress, Princess of Damascus | Soprano | Rosalie Levasseur |

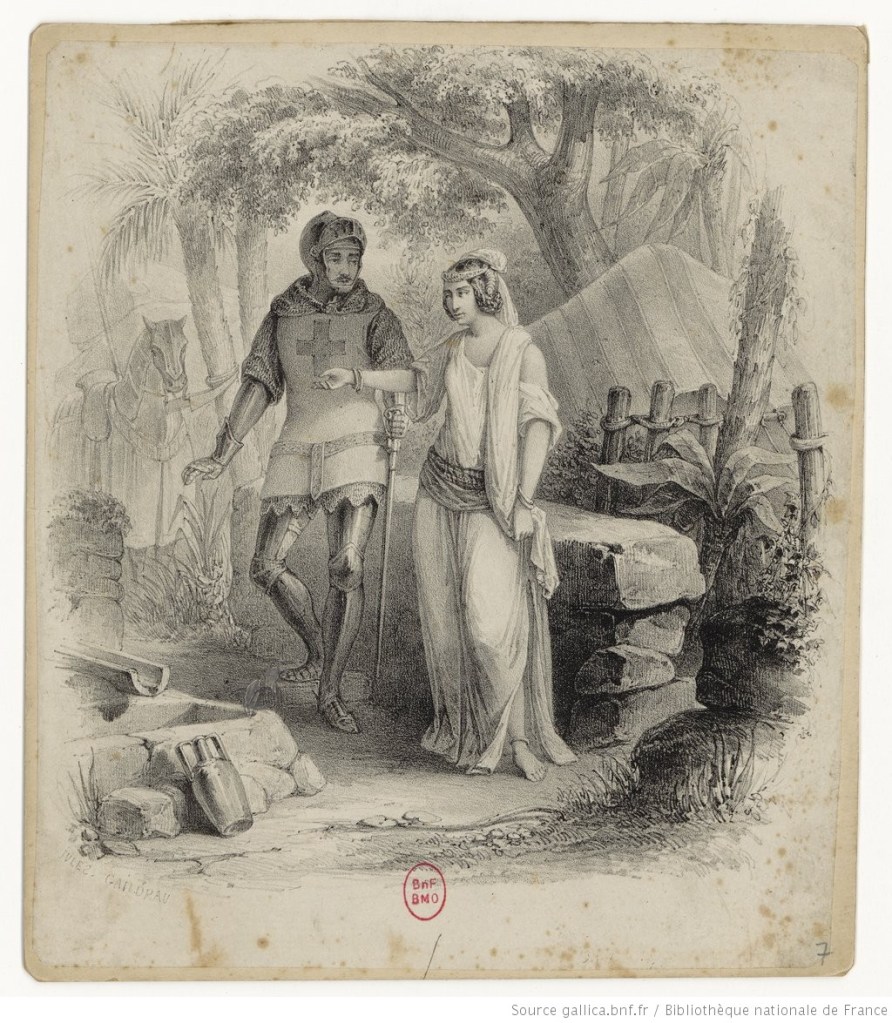

| RENAUD, A crusader | Haute-contre | Joseph Legros |

| PHÉNICE, Armide’s confidante | Soprano | Mlle LeBourgeois |

| SIDONIE, Armide’s confidante | Soprano | Mlle Châteauneuf |

| HIDRAOT, A magician, King of Damascus | Baritone | Nicholas Gélin |

| LA HAINE [Hate] | Contralto | Céleste [Célestine] Durancy |

| THE DANISH KNIGHT, A Crusader | Tenor | Étienne Lainez |

| UBALDE, A Crusader | Baritone | Henri Larrivée |

| A demon in the form of Lucinde, the Danish knight’s beloved | Soprano | Anne-Marie-Jeanne Gavaudan “l’aînée” |

| A demon in the form of Mélisse, Ubalde’s beloved | Soprano | Antoinette Cécile de Saint-Huberty |

| ARONTE, In charge of Armide’s prisoners | Baritone | Georges Durand |

| ARTÉMIDORE, A Crusader | Tenor | Thirot |

| A naiad | Soprano | Anne-Marie-Jeanne Gavaudan “l’aînée” |

| A shepherdess | Soprano | Anne-Marie-Jeanne Gavaudan “l’aînée” |

| A pleasure | Soprano | Antoinette Cécile de Saint-Huberty |

| People of Damascus, nymphs, shepherds and shepherdesses, suite of La Haine, demons, Pleasures, coryphaei | Chorus |

Gluck’s reform operas had set Paris ablaze: Iphigénie en Aulide and Orphée et Euridice in 1774, the French version of Alceste two years later.

His admirers hailed him as the apostle of music, as the fervent Wagnerites would the master of Bayreuth a century later. “There is only one truth in the world, and Gluck found it,” the actor Larrivée proclaimed. “I will not greet any man who doesn’t love Gluck’s music,” another enthusiast said.

But the lovers of Italian music thought otherwise. Gluck’s operas lacked melody; and he sacrificed vocal beauty and display to dramatic expression. (Of course, as the opera seria of Vinci show, we can have both!)

Even the court took sides: while Louis XVI supported Gluck, Marie Antoinette invited Niccolò Piccinni, the Italian composer of Neapolitan opera buffa, to Paris to show the French what real opera sounded like. Later, the Opéra directors would pit the two composers against each other, each composing an Iphigénie en Tauride.

Many a corpse lay outside theatres and cafés, pierced and bleeding from sword wounds. Their crime? They thought Gluck’s music untuneful, or Piccinni’s not energetic enough. Opera was not a song of love and death; it was a matter of life and death.

In fact, this whole quarrel was artificial; Piccinni’s talents were in a different sphere from the lofty Gluck’s – and the two men admired each other. (And Gluck’s advice to Piccinni? “Make money in Paris!”)

And then Gluck outraged the French. He committed what some called an artistic blasphemy: he dared to set one of Quinault’s libretti for Lully, and the most esteemed of all: Armide.

The opera, you will remember, tells of the love of the Saracen sorceress princess for the Crusader Renaud. He has bested the Saracen forces in battle; worse, he alone resists her charms. Armida lures him into a trap, and tries to kill him while he sleeps – but she cannot. Love stays her hand. She enchants him, and whisks him away to a magical garden … but the crusaders rescue him, and remind him of his honour. The abandoned Armide curses him, and, like Medea, destroys her palace.

A modern audience might object to the straightforwardly heroic presentation of the Crusaders, or a story about a Middle Eastern, Muslim woman – in league with the powers of hell, natch – seducing a white European man. At least this version doesn’t show Armide converting to Christianity, and becoming Renaud’s handmaid.

Armide contains much that is remarkable musically, but it’s hampered by Quinault’s libretto. The plot is disjointed, and often subordinated to spectacle. Characters fade in and out of the action: Renaud falls asleep in Act II, and doesn’t appear until Act V; Armide’s uncle Hidraot is prominent in the first two acts, then disappears. Act IV is dramatically redundant; and much of Act V is taken up with a long ballet / chorus divertissement.

It’s certainly more problematic than Gluck’s Greek tragedy operas. Ernest Newman suggests that he chose to set the text to prove that it was his skill, and not simply his librettists’, that secured those works’ success.

Nor is Armide and Renaud’s love as interesting as the sacrificial love, guilt, and reconciliation of the two Iphigénies or Alceste. It is inherently false, one-sided. Armide may love Renaud desperately, but he only loves her because he is (quite literally) underneath her spell.

Mario Armellini argues that Gluck wanted to challenge the founder of French opera, dead for nearly a century, on his own ground, and rejuvenate the tragédie lyrique with a more modern, naturalistic style, which transformed the older genre’s hierarchical relationship between music and text: “Lyrical declamation, gesture, harmony and orchestral commentary all worked together on an equal level to an expressive end, following procedures unknown as much to Rameau as to Lully.”

Certainly, the difference between Lully and Gluck is that between a child’s pencil drawing and a mediaeval Book of Hours, glowing with colour. Gluck himself wrote that he “tried to be a better painter and poet than a musician”.

Act I contains a majestic chorus (with dance) celebrating Armide’s victory over the crusaders: “Armide est encore plus aimable”.

A wounded messenger interrupts the festivities: Renaud has single-handedly rescued the Christian prisoners. The finale (“Poursuivons jusqu’au trépas”) begins with a whispered moderato, which sounds as if the Saracens are stealthily creeping up on their prey – then the music POUNCES! The act ends in a furious allegro, with the rhythmic élan of Rossini or the Act II Huguenots finale. (The corresponding scene in Lully is rather jolly.)

In Act II, Armide and Hidraot plot their vengeance in an electrifying duet, “Esprits de haine et de rage”. (This was also a highlight of Lully’s score.)

Renaud’s sleep scene, “Plus j’observe les lieux”, is one of the most beautiful sections in the opera. It opens with a lovely, winding, gentle ritornello, a duet of violin and flute. Renaud wanders by the stream, listening to birdsong, and slowly falls asleep on a meadow, under the shade of a tree.

All is pastoral and charming, with choruses of nymphs and shepherdesses, and a really delightful tripping chorus, “Ah! Quelle erreur, quelle folie”.

Newman was in rapture: “Nothing that Gluck had written up to this time was so uninterruptedly perfect as this; its voluptuous, cloying beauty is in marked contrast to much of his music, with its usual qualities of rigidity and reserve.”

The act ends with Armide’s famous “Enfin, il est en ma puissance”. Dagger in hand, she approaches Renaud – but cannot stab him. In “Venez, secondez mes desirs”, she summons demons (transformed into winds) to waft the pair (Renaud still unconscious) to a distant land; the orchestration is piquant, and ends with some unusual triplets depicting the beating of the zephyrs’ wings. (Massenet’s Esclarmonde is a more sympathetic version of the character.)

Act III features the scene where Armide summons la Haine (hatred) to drive love for Renaud out of her heart.

The whole sequence is astonishing, but la Haine’s “Amour, sors pour jamais” is the highlight: an obsessive and menacing aria over a series of repeated chords. The music is demonic; the sinister harmonies anticipate Meyerbeer. It’s not ‘melodic’ in the conventional sense, but suggests a terrible colourlessness, a world from which all love and warmth have been drained. It’s a glimpse into hell.

Act IV is a mere interlude. The Danish Knight and Ubalde steal into Armide’s realm to rescue Renauld – and are nearly seduced by demons disguised as their girlfriends. Newman thought it “both ridiculous in itself and wholly unnecessary as far as the opera is concerned.”

Gluck joked he would be damned for writing Act V (“Si je suis damné, ce sera pour avoir écrit Armide”) – but the love duet is very tame; it’s small beer compared to the languorous rapture or rapturous langur (more monkeys!) of the equivalent scene in Rossini’s Armida, or the lush eroticism of Wagner. Newman, however, thought the scene “the most voluptuously beautiful that ever came from Gluck’s pen… a foreshadowing of all that was most beautiful and most seductive in Romantic art.”

Mendelssohn also praised one of Renaud’s recitatives: “This piece has remained admirable despite age, despite the progress and transformations of art, like all that comes from the heart, like all that is a cry from the soul! Here is true music; thus have men spoken and felt; thus shall they speak and feel eternally!”

The opera ends with “Le perfide Renaud me fuit”, Armide’s cry of anguish as the Crusader abandons her. Despite the falseness of the situation, it’s a strong histrionic scene for the soprano, despairing then furious.

“I confess that it is with this opera I would like to finish my career,” Gluck wrote; “[but] it is true that the public will need at least as much time to understand it as they did for Alceste.”

If nothing else, the news of Gluck’s assault on Lully’s eminence attracted curiosity. Armide premiered before a full theatre – but the public remained cold, and only applauded certain passages.

La Harpe, a fervent Piccinnist, complained that there was neither melody nor singing in the new work; the role of Armide was, from start to finish, a monotonous and fatiguing shriek. “M. Gluck seems to have made it his task to banish song from the lyrical drama, and seems to be persuaded that song is contrary to dialogue, to the progress of the scenes, and to the ensemble of the action.”

Gluck retorted: “I was amazed when I saw that you had understood more about my art in a few hours of reflection than I have after practicing it for 40 years. You prove to me, sir, that it suffices to be a man of letters to speak of everything. I am now convinced that the music of the Italian masters is the music of the masters par excellence; that singing, to please, must be regular and periodic; and that even in those moments of disorder where the singing character is moved by different passions, passing from one to the other, the composer must keep to the same motif of song.”

La Harpe fired off a poem with the refrain: “Mais tout cela n’empeche pas | Que votre Armide m’ennuie.” The Gluckists retaliated with a barrage of satire – including the verses of a man who loved all instruments except … la harpe.

Within a few months, Gluck’s Armide had won over the public, and held the stage for 50 years, with major productions in 1866 and 1905.

Well into the twentieth century, it was considered one of Gluck’s masterpieces, even one of the most accomplished chefs-d’oeuvre of lyric art. Camille Bellaigue, in 1915, contrasted it favourably with Wagner’s “infected” Tristan und Isolde, combining musical criticism with nationalism:

Fût-ce pour avoir écrit Armide, Gluck n’aura point été damné, comme il le craignait, ou comme, avec un peu de coquetterie ou de fanfaronnade, il feignait de le craindre. Jusque dans la musique de sa partition la plus amoureuse, de celle qui répand, au sens initial et magique de ce mot, le « charme » le plus fort, la chair et les sens n’ont aucune part. On n’y respire point l’énervante, fiévreuse atmosphère, dont nous enivre et nous empoisonne un Tristan. Armide ne tend pas non plus, comme un Tristan toujours, et comme le dit l’Allemagne en son jargon, à la négation du vouloir vivre. Loin d’affaiblir notre être et de le dissoudre, la musique de Gluck l’accroît, le règle, et le discipline. Elle ne subordonne et ne sacrifie pas au sentiment, encore moins à la sensation, les droits de l’esprit et de la raison. Par cette maîtrise intellectuelle, Gluck est un de nos classiques, un Français d’autrefois, un de ceux que, pour notre salut, il nous faut redevenir. Et par la grandeur, par l’élévation morale de son art, il est un Français d’aujourd’hui. N’est-il pas, sur la scène, le musicien héroïque entre tous ? ,

Today, it is seldom performed, and Orfeo (wrongly) and Iphigénie en Tauride (rightly) are more esteemed.

SUGGESTED RECORDING

Mireille Delunsch (Armide), Charles Workman (Renaud), Laurent Naouri (Hidraot), and Ewa Podles (la Haine), with Marc Minkowski conducting Les Musiciens du Louvre, Paris, 1999. Archiv.

WORKS CONSULTED

- H. Barbedette, Gluck, Paris: Heugel & fils, 1882

- Félix Clément, Les musiciens célèbres depuis le 16ème siècle jusqu’à nos jours, Paris : Librairie Hachette & Cie, 1878

- Félix Clément, Dictionnaire des opéras, 1869

- Ernest Newman, Gluck and the Opera: A Study in Musical History, London: Bertram Dobell, 1895

- Jean d’Udine, Les musiciens célèbres : Gluck, Paris : Librairie Renouard, 1906

I prefer Haydn’s Armida. Gosh their were many operas based on this poem, same as Orfeo. They seem endless.

LikeLike

Yes – plus Handel (Rinaldo) and Dvorak!

Why do you prefer the Haydn?

LikeLike

I think it’s more musically inspired I suppose, that means more to me than if a work is just dramatic and nothing else(and I’m not saying Glucks Armida is rubbish, it’s quite good as well). Also, Haydn himself regarded it his finest dramatic work… who am I to disagree?

I must be honest but I do get weary of Gluck’s ”beautiful simplicity” at times it can get too much for me. Like you, I’m puzzled as how his Orfeo is so popular.

LikeLike

Armida is on my list.

There’s more than “beautiful simplicity” to Gluck! Intensity; dramatic power; characterisation! He’s at least as good as Mozart.

And, yes, Gluck wrote four – possibly five – better operas than Orfeo!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haydn’s Armida great too, I agree. But I find Gluck’s opera the best one.

@nickfuller , 5 operas superior to Orfeo?

Alceste, Armide an Iphigenie en Tauride (in this order in my opinion) are far superior.

Do you consider Iphigenie en Aulide and perhaps Paride ed Elena superior to Orfeo?

I think Iphigenie en Aulide might be a close match but I find Paride inferior.

What about his earliest operas? I think Il Parnaso Confuso and especially Il trionfo di Cleia awesome too!

LikeLike