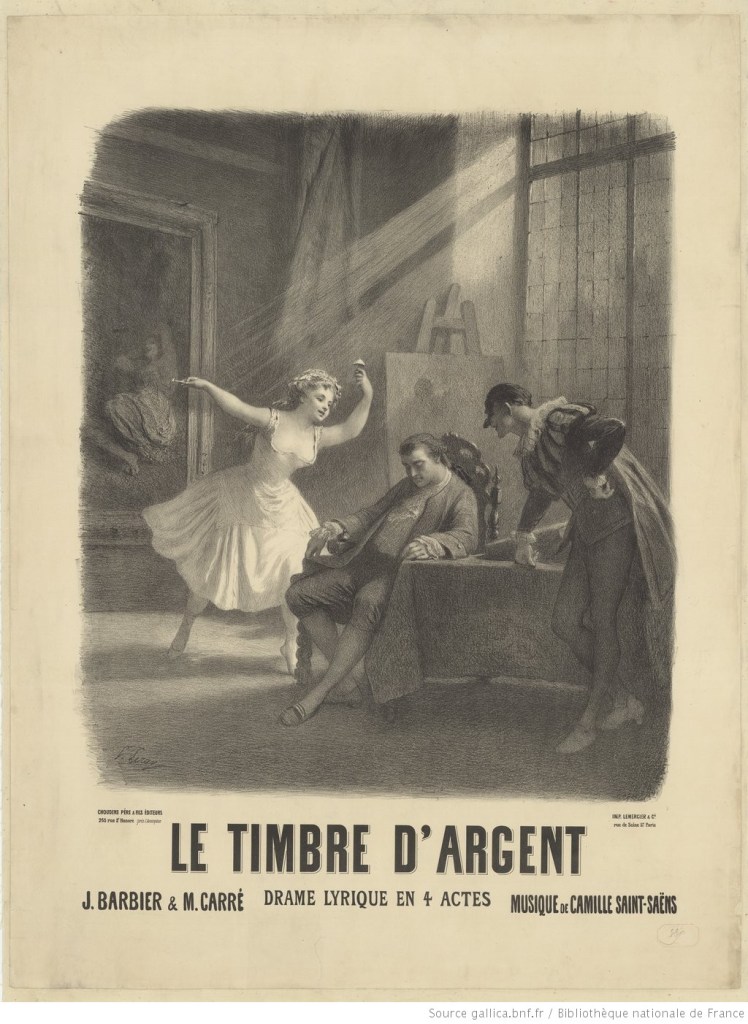

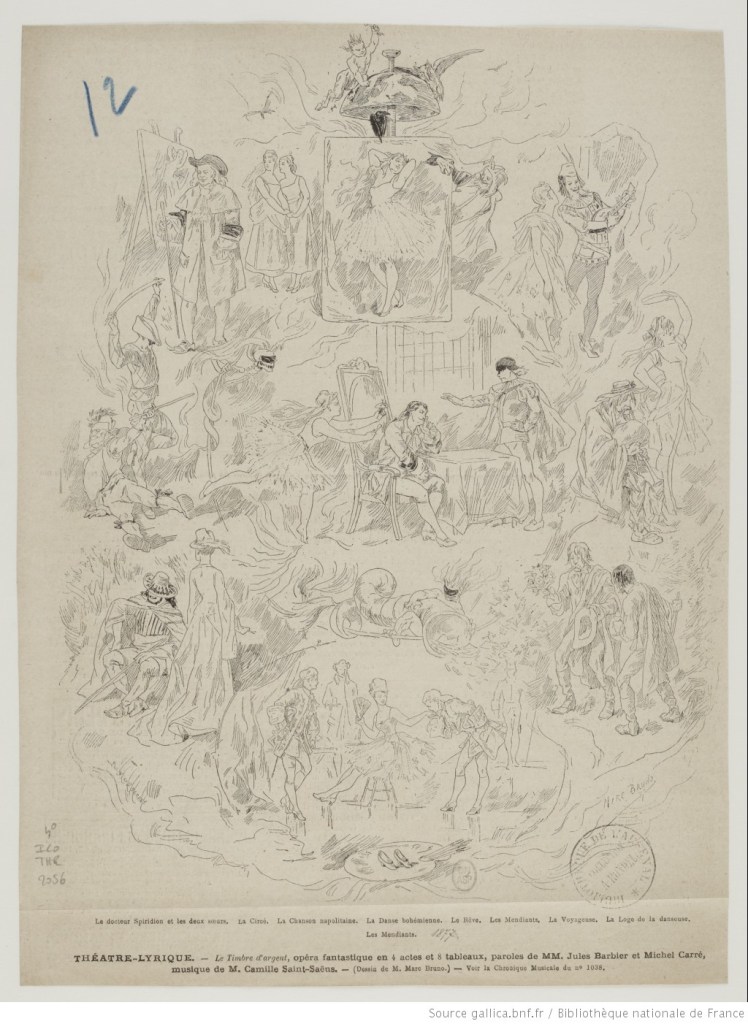

- Drame lyrique / opéra fantastique in 4 acts and 8 tableaux.

- Composer: Camille Saint-Saëns.

- Libretto: Michel Carré and Jules Barbier.

- First performed: Théâtre National Lyrique, Paris, 23 February 1877. Final version created at La Monnaie, Brussels, in 1914.

| CIRCÉE | Ballerina | Adeline Théodore |

| SPIRIDION | Baritone | Léon Melchissédec |

| HÉLÈNE | Soprano | Caroline Salla |

| CONRAD | Tenor | M. Blum |

| ROSA | Soprano | Mme Sablairolles |

| BÉNÉDICT | Tenor | M. Caisso |

| ROSENTHAL | Bass | M. Bonnefoy |

| FRANTZ | Tenor | M. Watson |

| PATRICK | Tenor | M. Aujac |

| RODOLPHE | Tenor | M. Demosy |

SETTING: Vienna, 18th century

Le Timbre d’Argent was Saint-Saëns’s first opera; it was only produced in 1877, more than a decade after it was written. Bru Zane’s recording comes out next month. I heard it in Paris (I won’t say ‘saw’; I had only a partial view of the stage), and I was glad to hear it again and better appreciate it.

PLOT

Le Timbre d’Argent is a phantasmagorical French counterpart to A Christmas Carol. “It’s no longer an opera, it’s a nightmare.” – Saint-Saëns, 1880

Act I: Conrad’s studio; Christmas Eve. Conrad, a struggling Viennese artist, is gravely ill with a fever; desire for money is eating him up from within, and he is infatuated with Fiametta, a beautiful but heartless ballerina (or erotic dancer), whom he has painted as the enchantress Circé. His physician, Spiridion, turns out to be the Devil; he brings Circé’s portrait to life, and gives Conrad a magical bell that will make him rich, but every time he strikes it, someone dies. His first victim is Stadtler the night-watchman, father of Hélène (in love with Conrad) and Rosa (engaged to Conrad’s best friend Bénédict).

Act II: The Vienna Court Opera (Fiametta’s dressing-room; backstage). With the money, Conrad tries to win Fiametta’s favours, offering her diamond necklaces and a party; he is outdone by Spiridion, who walks off with the ballerina. Bénédict, Conrad’s friend, invites him to his wedding the next day, and urges him to come back to those who love him – but his craze for the dancer is too great. Worse, Conrad’s steward has run away with his gold, leaving him penniless. Half-mad with anger, Conrad curses the partygoers, and rushes out in a frenzy.

Act III: An ivy-covered cottage by the Danube. Conrad comes to Bénédict and Rosa’s wedding, much to his friends’ joy; but Spiridion and Fiametta pursue him here. Intoxicated by Fiametta’s embrace, he rings the silver bell again – and Bénédict falls dead. Aghast, Conrad flees with Fiametta; Spiridion follows them, cackling triumphantly.

Act IV: Conrad tries to repent. He has thrown the silver bell into a moonlit lake; sirens urge him to take it up again, but he resists their call. Masked Carnival revellers pursue Conrad through the streets; in his madness, he thinks they are demons. He hears Hélène singing at her window, and goes to seek her forgiveness, but Spiridion, dressed as the devil, summons Circé and her nymphs; the daughters of hell urge him to strike the bell. Conrad calls on Hélène to help him; the Angelus rings out, and the dancers flee in terror. Hélène vows to protect Conrad, but he confesses that he broke her heart, and killed her father and her brother-in-law. Bénédict’s ghost appears, carrying the bell; Conrad smashes it. … And then wakes up, back in the studio. The action of the opera was all a dream! Cured from his gold madness, and from his lust for Fiametta, Conrad goes to church with his friends to celebrate Christmas.

COMMENTARY

My initial impressions (Paris, June 2017) were not favourable.

The Opéra-Comique is a beautiful theatre, the acoustics are excellent, but the sightlines were atrocious. My seat certainly wasn’t cheap, but I could only see half the stage. It was a modern dress and obviously low-budget production, and the tenor sounded strained and harsh. The music seemed correct but uninspired. The long overture, a buffo aria in the style of Offenbach, and ‘Le bonheur est chose légère’, the only aria ever recorded hitherto, were striking; the rest of the first act was boring. The second half seemed richer, especially a charming duet for the secondary couple, and the trio and Alleluia at the end. Several amusing special effects, including fireworks, spinning mirror balls sending dots of light around the auditorium, soloists moving through the ground level, and a chorus singing outside the auditorium or on balconies. But it was, I thought, far from a lost masterpiece. I woke up the next morning with a severe crick in my neck, and got through the day on Ibuprofen and Panadol. But I had seen a performance at the Opéra-Comique!

Le Timbre d’argent is not an easy opera to like, but it is an intriguing one – sombre, hallucinatory, and disconcertingly modern.

“There is everything in this work, from Symphony to Operetta via [Wagnerian] Drame Lyrique and Ballet,” Saint-Saëns wrote. “Nevertheless, the author has tried to give it a certain unity.” We find French declamation; pastiche Italianate numbers; brilliant orchestration; nocturnal choruses; pictures coming to life; rural weddings; blatant eroticism; and ballets of buzzing bees. Despite the kaleidoscopic variety of colour and incident, the work feels claustrophobic, almost as oppressive as Strauss’s Elektra.

Le Timbre d’Argent is a study in psychosis; it is a Freudian case study twenty years early. (Aptly, like Measure for Measure, that examination of sexual hysteria and licence, of id and superego, the opera takes place in Vienna.) It is obviously a link between the same librettists’ Faust and Contes d’Hoffmann, but its closest relation is perhaps Korngold’s Tote Stadt (1919), fifty years later. Madness is nothing new in nineteenth-century opera; sopranos are wont to go stark mad in white linen, and in extreme cases talk to flutes or their own shadow. Few operas of its century, however, are so subjective in their depiction of insanity. Conrad is a quasi-Wagnerian protagonist, obsessed, tormented, and damned. He loathes himself; he curses the day he was born; without hope or love, his heart is swollen with anger or hatred; and he hates his humble position, striving after riches and splendour. The overture itself seems like a tone poem of mental breakdown. It begins with a brilliant phrase from the Act II finale, then pushes this phrase through tonal and orchestral variations until the melody almost dissolves, disintegrates into madness. The coda shatters the theme into glittering shards.

The rest of the opera seems like a forerunner of Berg or of Bulgakov (Master and Margarita) in its absurdism. The narrative is a dream, shifting and unstable. So is identity; Spiridion dances through it adopting and discarding personae – a commedia dell’arte Dottore, a wealthy nobleman, an Italian poet, a coachman, a gypsy, the devil. Events and incidents multiply, in almost senseless profusion, with all the mad logic of a dream.

The very artifice of opera itself seems to break down; in one scene (Act II, tableau 2), the audience is brought face to face with itself. The set depicts the stage in reverse; at the back, we see the hall full of spectators, watching a ballet performance; the conductor stands in the middle, leading the musicians. (From memory, this was done with cameras and a video screen in the Paris production.) In the same scene, Spiridion transforms the theatre into a fantastical Florentine palace. Fully furnished tables arise out of the floor, chandeliers descend from the ceiling, and servants appear out of the wings, ready to serve a feast. “J’ai fait machiner le théâtre!” Spiridion remarks. The fourth wall wobbles, if it does not break.

The revelation in the last scene that all we have experienced is a dream may seem to cheat; certainly, Adolphe Jullien complained in the Revue et gazette musicale, that the awakening was like a shower of cold water; the more interest one took in Conrad’s woes, the more difficult it was to accept this reversal. But waking seems like a relief after the sustained horror of the previous three acts. Yet tendrils of dream still clog our minds; the ending does not fully convince, not because it is anti-climactic, but because the nightmare seems truer than daylight.

The complex score, moreover, must be heard at least twice, preferably three times, to appreciate. The score is effectively through-composed, despite division into orthodox numbers. Saint-Saëns, a symphonist by instinct, places the melody in the orchestra; many of the themes are short, and do not strike at first acquaintance. Attentive listening, however, reveals many subtle beauties or effective passages: for instance, the pensive and antiquated chords accompanying the doctor’s entrance; the ominous motif of the bell; and the shimmering flutes and distant horns when the painting comes to life (Act I); the frantic desperation of the gamblers, and the luminous theatre transformation scene (Act II); and the demented Carnival music, truly a carnival of the damned (Act IV).

Act I contains Bénédict’s melody ‘Demandez à l’oiseau qui s’éveille’; a sombre chorus warning of the perils of avarice; and the sisters’ prayer duettino, innocent and fresh. The only vaguely familiar aria in the opera, Hélène’s lovely romance ‘Le bonheur est chose légère’, accompanied by the violin, is found in Act II. This has been recorded by Frederica von Stade, Alma Gluck, and Ninon Vallin, among others. Also in that act are Spiridion’s chanson napolitaine, ‘De Naples à Florence’, a refreshingly catchy number, and a pastiche Italian brindisi.

Act III is perhaps the most melodic, and the most traditional section: a chorus of beggars (a moment of warmth and compassion); a rather attractive if conventional love duet; and a rustic wedding chorus, accompanied by the musette (rather in the style of Gounod’s Kermesse in Faust). Here, too, we find the most beautiful piece in the score, the exquisite chanson ‘Le papillon et la fleur’, sung by Rosa and Bénédict at their wedding. The act ends with the menacing, whirling gypsy chorus and Bénédict’s death, accompanied by bizarre harmonics.

The first scene of Act IV depicts a moonlit lake, full of sirens; its melancholy mystery is poised halfway between Berlioz or Gounod (Mireille) and Rimsky-Korsakov. The effect is magical.

Some pieces, however, were cut from the Paris production: a quintet in Act II, and the sisters’ duet in Act III. The recording seems to use the 1914 Brussels edition; those pieces may have been removed then. (The the Figaro critic noted that the duet baffled listeners.)

ORIGINS

Le Timbre d’Argent was composed fourteen years before it was finally performed; it was the work of a young man of 26 staged when its author was 42. It passed from the Théâtre Lyrique to the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique before returning to the Théâtre Lyrique, hampered by interfering impresarios, quarrelling librettists, miscast performers, and war. “Never has an opera undergone more transformations, encountered more obstacles, been tried out by more composers and been offered to more theatres than this unfortunate Timbre d’argent,” Adolphe Jullien (Revue et gazette musicale) reflected.

Saint-Saëns wryly commented (“Histoire d’un opéra comique”) on the travails he endured trying to have his opera staged. In 1864, in his late twenties, the young musician competed for the Prix de Rome for the second time; the jury (including Berlioz) knocked him back, because he had already established himself as a composer and organist. Our symphonist wanted to write operas.

Auber, the Conservatoire director, believed Saint-Saëns was worthier than the recipient, one Victor Sieg, and asked Léon Carvalho, director of the Théâtre Lyrique, to supply an opera libretto. Carvalho provided Le Timbre d’Argent, by Barbier & Carré, which Gounod and two minor composers (Xavier Boisselot and Henri Litolff) had already rejected.

With good reason, Saint-Saëns noted. The premise was excellent, favourable to music, but the libretto was hugely flawed. Barbier and Carré made the changes he requested, and Saint-Saëns composed the opera in two months.

Two years later, Carvalho deigned to hear the music. The impresario was enthusiastic; he wanted to stage it – if his wife, the prima donna Caroline Carvalho, sang the lead female role. But the part of Fiametta was for a dancer; Hélène’s role was much smaller. Carvalho was also an inveterate meddler; because the story turned out to be a dream, he saw it as a licence to invent the most bizarre scenes. Fill the stage with wild animals! Get rid of the music (except the choruses and the dances)! Mme Carvalho should dive into a giant aquarium! And so two years passed in what Saint-Saëns called this tomfool way (“niaseries”). Eventually, Mme Carvalho withdrew; the role of Hélène went to another singer; rehearsals began in 1867 or ’68 … And the theatre promptly went bankrupt.

Next, the Paris Opéra director, Émile Perrin, wanted to stage Le Timbre. The opera needed to be revised for the bigger stage; all the dialogue, for instance, had to be set to music. Perrin, too, had a mad idea: he wanted Conrad to be a soprano in travesti. The composer and the librettists protested; Perrin yielded, but it was obvious he would not stage the work either. (The score joined Reyer’s Sigurd, Bizet’s Don Rodrigue, an unnamed opera by Duprato, and Joncières’s Dernier jour de Pompéi in limbo.) Olivier Halanzier succeeded Perrin; he told Saint-Saëns quite plainly that he would never produce the opera.

So the score passed to the Opéra-Comique, where Perrin’s nephew Camille du Locle was director. The opera was revised yet again. This time Barbier and Carré, once close friends, quarrelled; anything one suggested, the other vetoed; and Saint-Saëns spent the summer travelling between their homes in Paris and the countryside trying to patch up the quarrel. Once that was resolved, a production seemed likely. Du Locle had found a beautiful dancer in Italy … but this dancer turned out to be a mime, who couldn’t dance.

Because there was no time to seek another dancer for the season, Du Locle commissioned Saint-Saëns to write La Princesse Jaune – the composer’s theatrical debut, at 35. The critics savaged the little work, to the composer’s bemusement, and it ended after five or six performances. Finally, a real dancer was hired in Italy.

Nothing seemed to oppose the appearance of the unfortunate Timbre any longer. “It’s unlikely,” Saint-Saëns told himself; “some catastrophe will get in the way.”

Then the Franco-Prussian War broke out.

The war ended; next, the tenor played up. He refused to sing the role, claiming that it was a grand opera role, and beyond his range as an opéra-comique singer. (That tenor, Saint-Saëns dryly remarked, finished his career at the Opéra.) By this time, Du Locle had lost interest in staging the work … and the Opéra-Comique collapsed.

Eventually, in 1876, the score came back like a boomerang to the Théâtre-Lyrique, which had commissioned the work a dozen years before. The company had gone bankrupt in 1872; five years later, Albert Vizentini resurrected the theatre. The Ministre des Beaux-Arts subsidised the venture, on the condition that the house staged Le Timbre.

The rehearsals were an ordeal; each day brought new annoyances for Saint-Saëns. Cuts were made against his will. The director and ballet master were rude to him. He had to pay for instruments himself. Stage business was declared impossible (it later appeared in Les Contes d’Hoffmann). The orchestra was mediocre, requiring many rehearsals. (At the fifteenth rehearsal, Fourcaud in the Gaulois observed, the orchestra was still lost in this maze of rhythm and harmonies.)

Many believed that the work was unperformable – an opéra fantastique indeed. Saint-Saëns, Joncières observed, was seen as an imitator of Berlioz and Wagner, a member of the School of the Future; his music was incomprehensible, and he was the enemy of melody. In fact, Fourcaud thought, the composer had a lofty ideal of opera, which he strove to achieve without any concession to the prejudices of the crowd; he had no fondness for those tunes the audience hums when leaving the theatre.

Well-informed people, Fourcaud noted (Gaulois), warned that the score would be the graveyard of any voices that tried to conquer it; they were the quicksands of this musical Mont-Saint-Michel. It was said that a fabulous number of singers had been swallowed alive at their first steps in the score; the quicksand definitely wanted victims. Only the tenor Léon Blum was able to escape alive, thanks to his Wagnerian training.

In fact, Saint-Saëns had found found a first-rate tenor – who refused the role … because Vizentini, not trusting the work, offered to hire him for four performances only.

At the last moment, Vizentini apparently realised that he was on the wrong track, and that the work could be a success. Caroline Salla took the role of Hélène. She was, Saint-Saëns remembered, a beautiful singer with a magnificent voice, but she was not well suited to the coloratura pieces written for Mme Carvalho; so people concluded that Saint-Saëns could not write for the voice.

The public were curious to hear this supposedly unperformable work. Fourcaud said he had rarely seen the corridors of the Théâtre-Lyrique livelier than at the first night; it was an incredible back-and-forth of conversations, a crossover of ironies and enthusiasm. Critics and dilettanti expected something unusual. The score had been published the day before; Joncières was impressed to see many in the audience carefully reading their scores.

RECEPTION

Le Timbre d’Argent was a moderate success. In Act I, Bénédict’s charming melody ‘Demandez à l’oiseau qui s’éveille’ was encored; Joncières thought this “absolutely exquisite” piece was the finest page of the score, because the emotion was real. The Figaro critic Bénédict called it a painting imbued with morning freshness, a song heard in the whitening dawn. In Act II, Spiridion’s chanson napolitaine aroused a storm of enthusiasm. Bénédict (Figaro) thought it was theatrical, fresh, and of rare rhythmic originality. Conrad’s cavatina ‘Nature souriante et douce’ (Act III) impressed the audience; here, Bénédict (Figaro) said, symphonist and melodist embraced. The Papillon et la Fleur chanson was also encored.

The libretto was much criticized. Bénédict (Figaro) described it as a series of tableaux that existed only to vary the spectacle, without much dramatic motivation. Joncières thought the chief defect was that the audience knew the story was a dream, making it difficult to care what happened. The Revue et gazette musicale thought the play seemed confused at first, but it seemed better upon reflection, and contained attractive episodes.

Saint-Saëns’s music was admired, with definite reservations. The critics of Le Figaro and Le Ménestrel believed Saint-Saëns was clearly a great musician, one of the great orchestrators of the day; few in France or Germany were his equal … but his opera was not theatrically effective. There were many remarkable parts, many picturesque and charming pages, but (Figaro said) it lacked inspiration and dramatic passion, the heart and marrow of any theatrical work. There were few of those simple but effective phrases that moved an audience (Ménestrel). Theatre music demanded simple lines and forms; Saint-Saëns’s instrumentation was as elaborate and chiselled as a work by Benvenuto Cellini, and the multiplicity of details harmed the work as a whole. Yet true music lovers would want to hear the score again.

For its use of the orchestra, Fourcaud (Gaulois) considered the opera by far the most interesting and the strongest since Berlioz’s Troyens. Sometimes, he admitted, the orchestra was overused, or the melody too much in the accompaniment, but he really didn’t care. The opera was a sort of Freischütz, where the sinister and mysterious alternated with the gentle, the graceful, and the real. There was everything in the score: superb discoveries, like the masquerade of the third act; ample phrases with patches of melody; brilliant fantasies; and monotonous pages where one heard nothing but the quivering of bows, the trembling of oboes and flute, the whispering of bassoons, and the cooing of trombones, covering indistinct ideas; and delightful ballet arias. The strengths were a thousand times more numerous and dazzling than the flaws of the work. A single hearing, however, was not enough to fully understand all the composer’s intentions. On leaving the theatre, the sixteenth notes danced in his ears, while the magical decorations and gleaming costumes still hurt his eyes.

Other critics felt the work was too uneven. Le Ménestrel thought this eclectic work could not satisfy the musicians of either the future or the past; it was written more than a decade before, when the composer had no preconceived system, but simply wanted to write a big score as best he could. Reyer thought it sinned by lack of unity; he expected a more homogeneous, more even, more sustained style. The Revue et gazette musicale called it a complex work, of a very disparate style, where the most contrary influences co-existed without cancelling each other out, where poetic and graceful pages sat next to vulgar and (astonishing from Saint-Saëns) commonplace ones. Lagenevais (Revue des deux mondes) made a similar complaint: the orchestration was masterly, but the melody was vulgar, bits of phrases that seemed to have been borrowed from the operetta repertoire. Reyer, leaving the theatre, was heard to exclaim: “It’s very good, but he lacks inexperience!”

Félix Clément (Dictionnaire des opéras) was scathing: “The story is a nightmare in four acts that lasts five hours.” The public found the work too long; hence it had only a few performances. The musician’s work was laborious, and Saint-Saëns had made persevering efforts to occupy a place among contemporary composers. But musical science, the obstinate search for novel symphonic effects, and the abuse of dissonance dominated the work; and whenever one noticed an actual melody, one was astonished at its lack of distinction.

Nevertheless, critics welcomed Saint-Saëns’s début as an opera composer. Le Ménestrel hoped he would become a worthy continuer of the French dramatic school; now it was up to him to compose a masterpiece. His first large score justified the state subsidy of the theatre; young composers finally had a theatre where they could produce their works.

“As everyone knows,” Saint-Saëns wrote, “it is only by forging that one becomes a blacksmith; one doesn’t gain experience and develop one’s talent waiting under an elm. We would never have known the heyday of the Théâtre-Italien if Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini and Verdi had been subjected to this regime; and if Mozart had to wait until his forties to produce his first opera, we would have neither Don Giovanni nor The Marriage of Figaro, since Mozart died at thirty-five. The internship imposed on Bizet and Delibes certainly deprived us of several works which would now be the honour of the opera and opéra-comique repertoires. It is an irreparable misfortune which we can never deplore enough.”

Bizet himself had arranged the score for piano before he died in 1875. “It’s charming! A real opéra-comique sprinkled with a little Verdi. What a fantasy! What brilliant melodies! – From Wagner, from Berlioz, nothing! Nothing! Nothing! – You will be amazed! – Two or three songs are a bit vulgar, but they’re appropriate to the situation, and then it’s saved by the musician’s immense talent. This is a real work, and he is a real man!” Bizet compared the score to Auber. Joncières felt he was right; it had the clarity and concision of Auber, but with more elaborate orchestration and harmony.

PERFORMANCE HISTORY

Le Timbre d’argent was staged 18 times that season – an honourable success, Saint-Saëns believed, particularly thanks to the baritone Léon Melchissédech (singing Spiridion) and the ballerina Adeline Théodore. Vizentini changed his opinion of Saint-Saëns’s music, and became a close friend; as director of the Grand-Théâtre of Lyon, he presented the ballet Javotte. He later dreamt of managing the Opéra-Comique, and of staging the Timbre there.

The opera was performed at La Monnaie in Brussels in 1879 (20 performances); in Germany in 1904-05; in Monte Carlo in 1907; and finally, in Brussels again in 1914.

More than a century later, it was resurrected in Paris in 2017, given at the Opéra-Comique in a production by Guillaume Vincent, featuring the ballerina Raphaëlle Delaunay, the tenors Edgaras Montvidas (Conrad) and Yu Shao (Bénédict), the soprano Hélène Guilmette (Hélène), and the baritone Tassis Christoyannis (Spiridion), with Les Siècles conducted by François-Xavier Roth. Montvidas is not the most attractive tenor, but shows considerable stamina in a long, demanding part; Christoyannis is excellent as always; and one can hear every detail of the complex score.

WORKS CONSULTED

- Camille Saint-Saëns, École buissonnière : Notes et souvenirs, Paris : P. Lafitte & Cie., 1913

- Bénédict, Figaro, 25 February 1877

- H. Moreno, Le Ménestrel, 25 February and 4 March 1877

- Revue et gazette musicale, 25 February 1877 ; Adolphe Jullien, 4 March 1877

- Fourcaud, Le Gaulois, 26 February 1877

- Ernest Reyer, Journal des débats, 27 February 1877

- Victorin Joncières, La Liberté, 5 March 1877

- F. de Lagenevais, Revue des deux mondes, 14 April 1877

- Félix Clément, Dictionnaire des opéras, supplement 1880

- Programme, Opéra-Comique, 2017

- Un cauchemar envoûtant

- Marie-Gabrielle Soret : La genèse du Timbre d’argent

- Gérard Condé : Bien plus qu’un galop d’essai

- Stéphane Lelièvre : Un livret sous influences

This one should – I think – be issued on Bru Zane in the not too distant future.

LikeLike

Yes, 28 August.

https://www.fnac.com/a14927138/Camille-Saint-Saens-Le-timbre-d-argent-CD-album

LikeLike

If all goes well with regards to covid – Saint-Saëns/Guiraud Frédégonde and his Déjanire should also be recorded on Bru Zane as well.

LikeLike

Good! Where did you find this out?

LikeLike

http://www.unsungcomposers.com/forum/index.php/topic,6931.15.html

Nothing certain anymore with the pandemic though.

LikeLike