The German composer Paul Hindemith (1895–1963) wrote music “as a tree bears fruit”, Albert Einstein remarked. His prolific output, ranging from late-Romantic influences to neoclassical and modernist tendencies, includes symphonies, concertos, chamber music, ballets, choral works, solo pieces for a wide range of instruments – and 11 operas (including a collaboration with Bertolt Brecht).

His operatic beginnings were rocky. They consist of a triptych of single-act works, dealing with the battle of the sexes, castration, and a nun’s sexual awakening. They impressed critics, but scandalised contemporary audiences.

Zeitschrift für Musik (1922) condemned the three operas: the libretti were “absolutely worthless”. “Hindemith’s music circles along the lines of restless expressionism; without any sense of melody… monstrous chords are piled up by the overloaded orchestra, then again there is a yawning emptiness.”

Hindemith withdrew the works from public performance in the 1930s, and they were not performed again until after his death. Even today, they can still shock.

Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (op. 12)

- Opera in 1 act

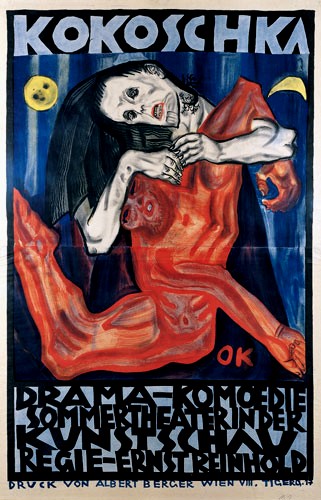

- Libretto: Oskar Kokoschka

- First performed: Würrtembergisches Landestheater Stuttgart, Germany, 4 June 1921

| The Man | Baritone | |

| The Woman | Soprano | |

| Warriors | 2 tenors, 1 bass | |

| Maidens | 2 soprani, 1 alto |

Setting: Antiquity

Murderer, Hope of Women. Here is an opera with a title that only an extremist feminist like Valerie Solanas would agree with, but whose themes are closer to men’s rights activism. The opera was an adaptation of Oscar Kokoschka’s 1909 play, considered the first Expressionist work, an approach that focuses on subjective emotional experience, rejects traditional artistic conventions, and tries to express inner feelings and anxieties. Kokoschka’s play (according to Michael Navratil) also drew on the Viennese Modernist idea that rationalist (male) culture was lifeless, and could only rejuvenate itself through violence; Otto Weininger’s concept of gender relations as a battle between (superior, spiritual) man and (debased, bestial) woman; and, of course, Nietzsche and Freud.

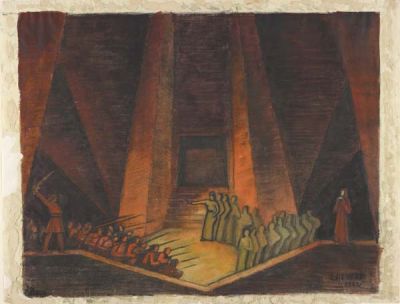

The opera takes place in abstract ancient times, outside a tower with a large iron gate, at night. It is all very symbolic. The characters are the Man and the Woman (definite articles). The Man, leader of the warriors, has the Woman branded with a red-hot iron; she stabs him; he is wounded, but recovers by draining her life force, then kills everyone else “like mosquitoes”. He escapes, while the tower goes up in flames and a cock crows.

Hindemith’s score – conceived as a four-movement sonata – is sombre and effective, particularly the dissonant prologue with its ominous recurrent five-note theme.

However, the Zeitschrift critic dismissed this opera as “completely incomprehensible drivel”, and he had a point. The dialogue throughout is cryptic and as pretentious as the worst of Tristan und Isolde. Here is a sample:

THE MAN (in spasms, singing with a visible, bleeding wound)

Senseless desire from terror to terror, Sinnlose Begehr von Grauen zu Grauen

Unquenchable circling in the void. Unstillbares Kreisen im Leeren.

Birth without birth, sunfall, wavering space. Gebären ohne Geburt, Sonnensturz, wankender Raum.

The end of those who praised me. Ende derer, die mich priesen.

Oh, your merciless word. O, euer unbarmherzig Wort.

…

THE MAN (within, breathing heavily, slowly raises his head, later moves one hand, then both hands, slowly rises, singing, entranced)

A wind that pulls, time after time. Wind der zieht, Zeit um Zeit.

Solitude, rest, and hunger confuse me. Einsamkeit, Ruhe und Hunger verwirren mich.

Passing worlds, no air, evening lasts. Vorbeikreisende Welten, keine Luft, abendlang wird es.

…

THE MAN (powerfully)

Stars and moons! Woman! Sterne und Mond! Frau!

Shining brightly in dreams or waking, Hell leuchten im Träumen

I saw a singing being… oder Wachen sah ich ein singendes Wesen…

Inhaling, the dark becomes clear to me. Atmend entwirrt sich mir Dunkles.

Mother… You lost me here. Mutter . . . Du verlorst mich hier.

Nevertheless, Mörder struck a chord with a German audience recovering from its defeat in the War. Kurt Pahlen considered the opera “a milestone of an almost unmanageable, confusing epoch of the end of the war, collapse, downfall, fanaticism”. Likewise, Raymond Lübbers suggests that “the immense mechanisation and shock of the First World War” were reflected in Expressionism’s “vivid, often brutal style”. “Clear emotional expressions and plot developments are often countered with contradictory or incomprehensible text passages, creating a sense of fragmentation, similar to what the tower at the end of the opera or even society at the end of the First World War may have experienced”.

Recordings

Listen to: Franz Grundheber (The Man) and Gabriele Schnaut (The Woman), with the Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, conducted by Gerd Albrecht, Berlin, 1989. YouTube.

Das Nusch-Nuschi (op. 20)

- Play for Burmese marionettes in 1 act

- Libretto: Franz Blei

- First performed: Würrtembergisches Landestheater Stuttgart, Germany, 4 June 1921

| MUNG THA BYA, Emperor of Burma | Bass | |

| RAGWENG, the Crown Prince | Speaking rôle | |

| Field-General KYCE WAING | Bass | |

| The Master of Ceremonies | Bass | |

| The Executioner | Bass | |

| A Beggar | Bass | |

| SUSULÜ, the emperor’s eunuch | Tenor (falsetto) | |

| The handsome ZATWAI | Silent | |

| TUM TUM, his servant | Tenor buffo | |

| KAMADEWA, god of desire | Tenor or soprano | |

| Two heralds | Bass, tenor | |

| The wives of the emperor | ||

| BANGSA | Soprano | |

| OSASA | Coloratura soprano | |

| TWAÏSE | Alto | |

| RATASATA | Soprano | |

| Two Bayaderes | Soprano, alto | |

| Two trained monkeys | Tenors | |

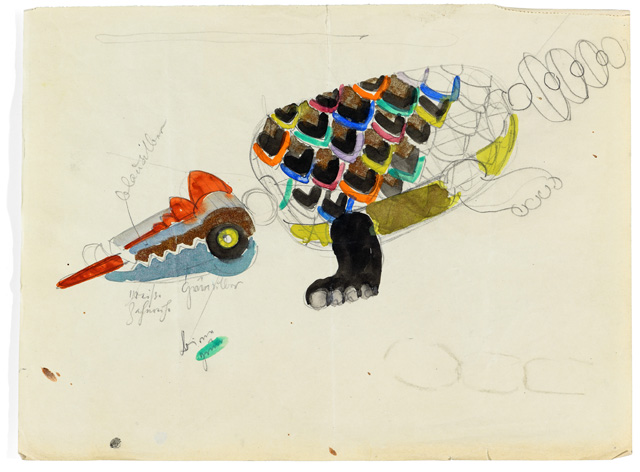

| The Nusch-Nuschi | ||

| Two poets | Tenor, bass | |

| Three girls | 2 soprani, 1 alto |

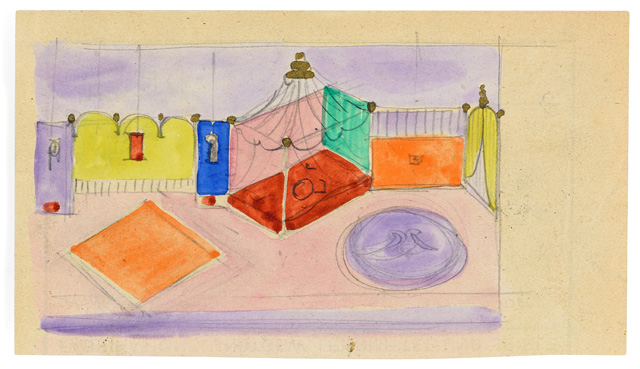

Setting: Burma, in the empire of Emperor Mung Tha Bya

Mörder shared its opening night bill with the risqué Nusch-Nuschi, a work in complete contrast. This has a work that has intrigued me ever since I read Gramophone’s review: “An alluringly vivid kaleidoscope of orientalisms, lyrical arabesque, languorous allure, and brilliant colour” – saddled with an impossible story. (“Please don’t ask me to explain the plot… You won’t ask me about the plot, will you?”)

In fact, the plot is in the spirit of Hervé or Offenbach’s burlesques, complete with its own subgenre: “Play for Burmese marionettes”. Briefly, Zatwai, a nobleman, has fallen in love with one of the Burmese emperor’s wives, and sends his servant Tum Tum to bring the woman to him. In fact, Zatwai had caught the eye of all four of the women, who each escapes from the palace down Tum Tum’s rope ladder. Tum Tum also saves the (very drunk) Field-Marshal Kyce Waing from the Nusch-Nuschi, half-rat, half-caiman; the Field-Marshal engages Tum Tum as his new servant. That night, Zatwai enjoys a night of love with the Burmese queens – but Tum Tum is arrested, and sentenced to be castrated. I shan’t spoil what happens; it’s a clever little twist. But it might reflect German disillusionment after the war.

The musical highlight is Scene 2, which depicts Zatwai’s encounters with the queens. It opens with a lush orchestral interlude. Bayaderes sing a melody in G major – the tune is lovely, but the lyrics are innuendoes galore (flowers opening their petals, sweetened mouths raising the godly spear, bowmen shooting arrows of love onto the trembling flowers, etc.). Trained monkeys sing “Rai! Rai! Rai!” There is a brilliant Oriental-style dance, culminating, Hindemith instructs, in a choral fugue “danced (or rather wobbled to) by two eunuchs with incredibly fat and naked bellies”! Otherwise, throughout the opera, Hindemith uses lots of tinkling xylophones and gongs, bells, and cymbals to create an Oriental colour.

The premiere was enthusiastically acclaimed, but there were riots on the second night, from protesters who found Mörder too violent and both operas sexually immoral. (The next year, the Zeitschrift called it “a spicy lewdness for decadent pleasure-seekers”.) Even worse, Hindemith poked fun at Wagner. (The Burmese emperor quotes Märke’s reproach from Tristan.) This was, of course, the same composer who sent up the master of Bayreuth with his Overture to the ‘Flying Dutchman’ as played by a bad spa orchestra at 7 in the morning by the fountain (one of the great musical jokes).

Recordings

Listen to: Wilfried Gahmlich (Tum-tum), Georgine Resnick and Gisela Pohl (Bayaderes), etc., with the Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, conducted by Gerd Albrecht, Berlin, 1988. YouTube.

Sancta Susanna (op. 21)

- Opera in 1 act

- Libretto: August Stramm

- First performed: Opernhaus Frankfurt am Main, 26th March 1922

| SUSANNA | Soprano | |

| KLEMENTIA | Alto | |

| An Old Nun | Alto | |

| A Maid | Speaking rôle | |

| A Servant | Speaking Rôle | |

| Nuns | Women’s chorus |

Setting: In a monastery church, May night

Sancta Susanna might have been the most shocking German opera since Richard Strauss’s Salome (1905), nearly two decades before. It was “obscene” (Fritz Busch, who refused to conduct it); “a perverse, truly immoral affair” (Zeitschrift); and “a desecration of our cultural institutes” (Karl Grunsky). The Christian-conservative Stage People’s Association wanted it banned; and the Catholic Women’s Federation held a three-day prayer service for atonement. Even today, it infuriates the Christian right.

Salome featured a teenage girl who has an orgasm over the severed head of John the Baptist; Sancta Susanna gives us another sexual neurotic: a nun (sexually repressed, of course) who tears off her habit, revels in her beauty, tears the loincloth from the statue of Christ, and then demands to be walled up, like a previous nun who took off all her clothes and embraced the icon. (The 2012 Lyon production had the soprano fully naked, with a frisson of lesbianism to boot.) Opera has had a thing about naughty nuns since at least the 1830s (Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable), but this is probably the most extreme example.

While Sancta Susanna is designed to shock, it is a surprisingly powerful little work, and the score, from its slow prelude (“Very slowly; with expression and warmth”) to the overwhelming shouts of “Satana!” and ffff chords at the end, is consistently effective. Hindemith himself considered it his most successful one-act work. The musicologist Paul Bekker called it “a musical fantasy on a single theme of strangely plaintive, longing appeal, which draws ever larger circles of passion and desire to the point of thunderstorm-like discharge and liberation”. By 1930, its notoriety had established Hindemith, in the opinion of Marion Scott (Proceedings of the Musical Association), as “the acknowledged leader of the ‘new music’”.

Recordings

Listen to: Helen Donath (Susanna) and Gabriele Schnaut (Klementia), with the Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, conducted by Gerd Albrecht, Berlin 1983. YouTube.

Watch: Agnès Selma Weiland (Susanna) and Magdalena Anna Hofmann (Klementia), with the Opéra de Lyon, conducted by Bernhard Kontarsky, Lyon 2012. YouTube.

Works consulted

- Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (opera) – Wikipedia

- John Henken, Murderer, Hope of Women, Paul Hindemith (laphil.com)

- Raphael Lübbers, musirony – Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen

- Michael Navratil, German Literature – Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (google.com)

- Das Nusch-Nuschi – Wikipedia

- Michael Oliver, Nusch-Nuschi, Gramophone

- Sancta Susanna – Wikipedia

One thought on “253. Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen / Das Nusch-Nuschi / Sancta Susanna (Hindemith)”