- Opera in 3 acts

- Composer: Paul Hindemith

- Libretto: Ferdinand Lion, after E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “Das Fräulein von Scuderi”

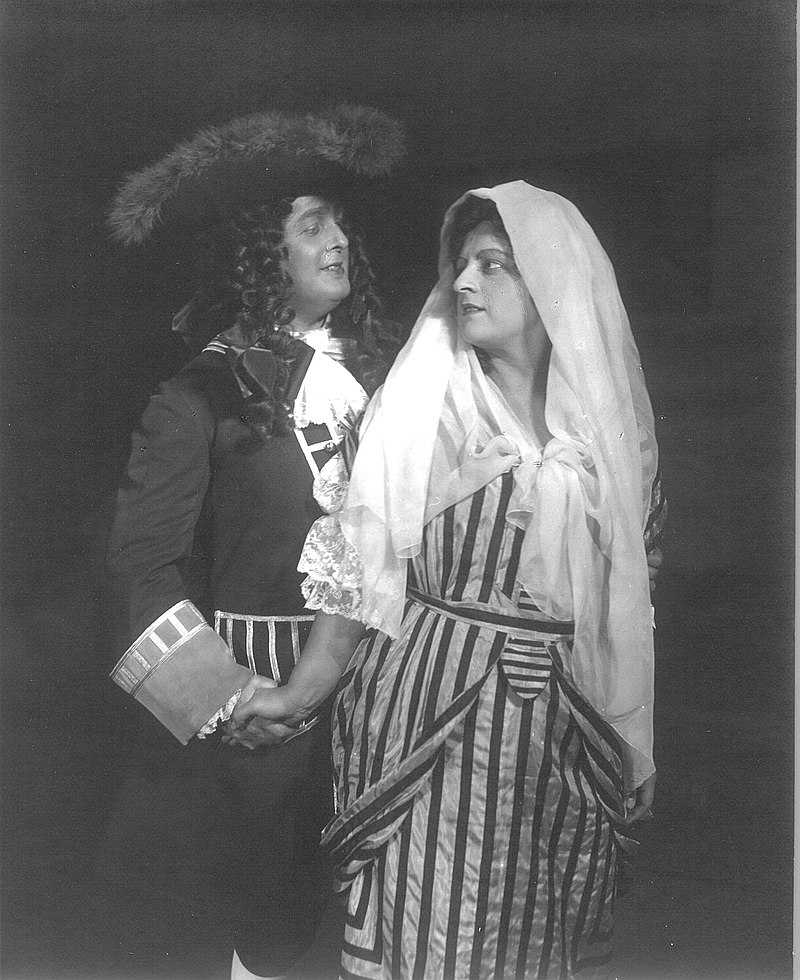

- First performed: Staatsoper, Dresden, Germany, 9th November 1926, conducted by Fritz Busch

Characters

| The Goldsmith CARDILLAC | Baritone | Robert Burg |

| The Daughter | Soprano | Claire Born |

| The Officer | Tenor | Max Hirzel |

| The Gold Merchant | Bass | Adolph Schoepfin |

| The Cavalier | Tenor | Ludwig Max Eybisch |

| The Lady | Soprano | Grete Merrem-Nikisch |

| The Provost Marshal | Bass | Paul Schöffler |

| The King Cavaliers and Ladies of the Court The Prévôte People |

Setting: Paris, 17th century

Five years before Fritz Lang’s M (1931), Hindemith beat him to the punch with a grim opera about a serial killer and mob violence. Cardillac is Hindemith’s most successful opera (although Mathis der Maler, twice as long, is supposedly his operatic masterpiece), but has never won much popular favour. In the last 30 years, it has only been performed in Vienna (according to Operabase), Munich, and Paris. Theatrically effective, but atonal and almost tuneless, it is, as The Guardian’s Andrew Clements remarks, “a hard opera to love”.

Paris is in the grip of terror: thieves are stabbing people who buy jewellery from the goldsmith Cardillac, whose jewellery rivals and surpasses the splendour of the Florentine masters. The people suspect each other: in their fear, they attack boys, deaf-dumb mutes, and fools. But the culprit is Cardillac himself, who cannot bear to part with a single one of his works; like Alberich and Fafner, his is a possessive, miserly love (“Could I love what doesn’t entirely belong to me?”). He is indifferent to his daughter, who, like Rachel in Halévy’s La Juive, another daughter of an obsessed goldsmith, hesitates between her father and her lover, an Officer. The boyfriend buys a chain from Cardillac’s workshop, and the goldsmith tries to murder him. But the Officer, recognising that their monomaniacal love – one for gold, the other for a woman (his “dearest possession”), makes them kindred spirits – declares that Cardillac is not his attacker. Cardillac, proud of his crime, boasts that he is the murderer, and the incensed crowd kills him. The Officer, however, calls Cardillac “a hero”, because he was “unfamiliar with human fear – though he lies here, he is still the victor, and I envy him”.

Cardillac, according to Neumeyer, is “the most successful and most characteristic German opera in modern style of the mid- and late-Twenties”. It represents the New Objective Manner: “frankly antiromantic, a rejection of pre-World War expressionism and an affirmation of a new urban culture – society as a city-machine. The New Objective composers substituted linear, kinetic energy and deliberate formal constructivism for the nineteenth century’s psychological development (motivic working and endless melody), functional harmony, and sensuous orchestral timbres.” Instead, we have linear counterpoint: “cells of diatonic figures mixed without regard for key origins, the half-step as a general leading tone, and sharply accented rhythmic notes”. Fans of dissonance will enjoy the result.

Cardillac is ostensibly a number opera (the score is divided into 18 numbers, including Arias, Lieder, and Duets); but don’t expect any other concessions to popular taste. Hindemith’s music, as Clements puts it, is “uncompromisingly dry, motoric”. Like Berg’s Wozzeck (1925), it employs Baroque forms (fugato for Cardillac’s scene with his daughter, a passacaglia for a crowd scene). This was Hindemith’s response to Handel’s operas, being revived at the time. Hindemith wanted “a structure based on a succession of musical numbers in a variety of strict polyphonic forms”, in order to “objectivise the action by deliberately clothing the romantic subject in a contrapuntal framework”, Skelton states. But devoid of melodic inspiration, this seems like barren technique – something that will please musicologists who can study the score at their leisure, but will be lost on opera audiences who want a tune. The press complained at the time that Hindemith’s “soberly unromantic” music “has almost nothing to do with the romanticism of the material, with the warmth of the feeling and so on”. Kaminski notes that Hindemith’s almost formalistic detachment, asserting the independence of the music from the stage action and the characters’ psychology, was widely criticized.

Act I begins with a powerful polyphonic choral scene (“Mörder! Verborgen!”), depicting the Parisians fear and tendency to violence. The Lady’s Lied (“Die Zeit vergeht, Rose zerfiel”), waiting for her lover to bring her a Cardillac piece, is sensuous; while the music accompanying the ensuing pantomime is largely orchestral noodling, the sex scene and murder (in the 1985 Munich production, Cardillac’s knife-brandishing shadow silhouetted on the wall, like something out of Murnau) are theatrically effective. Act II, however, is a tuneless din: ostinato rhythms and whooping brass punctuated by percussive explosions and thuds. The ear wants relief from this barrage, so even brief snatches of jazz from the tavern at the start of Act III offer welcome respite. More surprising is the quartet (“Den Himmels Huld”), broadly along classical lines (although in no recognisable key, of course). The murder of Cardillac is utter cacophony. The Final Chorus brings the opera to a sedate close. (Does a serial killer really merit this hymn-like piece, however?)

Cardillac met with a mixed reaction; Skelton notes that some critics “hailed it as an important advance in operatic form”, and it was produced at 13 other German opera houses until 1932. Hindemith revised the opera in the 1950s. After attending a 1948 performance, he reflected: “The music holds up quite well. Most of the pieces are still enjoyable, so that the score could be rescued musically with a few relatively minor alterations. On the other hand, the libretto is unfortunately so idiotic that, if the piece is to survive, the whole action will have to be completely changed.” Hindemith expanded the plot to four acts. This version was first performed in 1952, but, despite Hindemith’s efforts to ban the original version, the revision never took hold. Skelton does not consider the revised libretto an improvement; in his opinion, the action is more diffuse, and Cardillac’s character weakened.

Hindemith, however, was wrong. The libretto (a rare instance in opera) is much better than the music; the score is a Cardillac affliction.

Recordings

Listen to: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (Cardillac), Elisabeth Anna Sörderstrom (the Daughter), and Donald Grobe (the Officer), with the Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie Orchester, conducted by Joseph Keilberth, Cologne, 1969.

Watch: Donald McIntyre (Cardillac), Maria de Francesca-Cavazza (the Daughter), and Robert Schunk (the Officer), with the Bayerische Staatsoper, conducted by Wolfgang Sawallisch, directed by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, Munich, 1985.

Works consulted

- Geoffrey Skelton, Paul Hindemith: The Man Behind the Music, London: Victor Gollancz, 1975

- David Neumeyer, The Music of Paul Hindemith, New York & London: Yale University Press, 1986

- Piotr Kaminski, Mille et un opéras, Paris: Fayard, 2003

- Andrew Clements, “Hindemith: Cardillac review – fine performance of a hard opera to love”, The Guardian, 14 July 2023

- “Cardillac”, Wikipedia (German)

- “Cardillac”, Paul Hindemith

- S. Sch.-G, “Cardillac”, Schott Music Group