- Composer: Bernd Alois Zimmermann

- Opera in 4 acts

- After the play by Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz

- First performed: Cologne Opera, 15 February 1965

Characters

| WESENER, a fancy goods merchant in Lille | Bass | Zoltán Kelemen |

| MARIE, his daughter | Soprano | Edith Gabry |

| CHARLOTTE, his daughter | Mezzo | Helga Jenckel |

| Wesener’s Old Mother | Contralto | Maura Moreira |

| STOLZIUS, a draper in Armentières | Baritone | Claudio Nicolai |

| Stolzius’s Mother | Contralto | Elisabeth Schärtel |

| OBRIST GRAF VON SPANNHEIM | Bass | Erich Winckelmann |

| DESPORTES, a nobleman from French Hainault serving in the French army | Tenor | Anton de Ridder |

| PIRZEL, a Captain | High tenor | Albert Weikenmeier |

| EISENHARDT, Army chaplain | Baritone | Heiner Horn |

| HAUDY and | Baritone | Gerd Nienstedt |

| MARY, field officers | Baritone | Camillo Meghor |

| Three young officers | Tenors | Norman Paige Hubert Möhler Heribert Steinbach |

| GRÄFIN DE LA ROCHE | Mezzo | Liane Synek |

| The Young Graf, her son | Tenor | Willi Brokmeier |

| The Gräfin de la Roche’s servant | Spoken | |

| Desportes’s gamekeeper | Spoken | |

| Andalusian waitress | Dancer | |

| Madame Roux, coffee-house owner | Mute | |

| A young ensign | ||

| A drunken Officer | ||

| Three captains | ||

| Officers and ensigns |

SETTING: Lille and nearby Armentières in French Flanders. Time: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

Die Soldaten is a war survivor’s existential scream, the work of a composer with PTSD, and a symptom of German cultural trauma. Zimmerman too was a soldier — and, Berry1 suggests, he never fully demilitarised. The Nazis closed the monastery where he was studying to become a monk, and conscripted him into the army: he fought on both fronts of the war as a member of the Wehrmacht (1940 to 1942): Paris, Poland, Russia. At the end of the war, he considered killing himself. He resented Allied denazification of soldiers as persecution. After the war, instead of becoming a priest as he had intended (loss of faith? of meaning?), he became a musician. He suffered from depression, and committed suicide in 1970.

Die Soldaten has been called the most important contemporary opera since Lulu, but it doesn’t make my heart go boom-bang-a-bang. It is neither musically nor dramatically engaging, and makes almost no impression. The story is wannabe Berg: a cross between Wozzeck (the dehumanising effect of the army) and Lulu (the degradation of a prostitute). (Wozzeck’s Büchner wrote a novella about Soldaten’s Lenz.) The music is wannabe Berg too: Soldaten borrows both the division of the score into classical structures (chaconnes, toccatas, and so on) and the technique of Sprechgesang (speech singing) — i.e., recitative without the melody. “The vocal parts are simply not easy to sing,” the conductor Bernhard Kontarsky2 explains, “they contain extreme vocal registers, interval jumps, changes of register and tricky rhythms.”

It is extremely German: sententious coffee-house debates about metaphysics alternate with rape and violence. Marie, a merchant’s daughter from a good middle-class family, has relationships with various soldiers; one of them gives her to his gamekeeper, who rapes her. The libretto states it is “an allegory of the rape of all those involved in the action: a brutal, physical, psychological and spiritual rape”. Marie becomes a prostitute. Her own father does not recognise her, and she collapses, “utterly destroyed”. The opera ends with an unbroken column of the dead marching into the darkness. Thirty-two floodlights blind the audience. Tellingly, Zimmermann’s next operatic project would have been Medea, in which a mother butchers her children.

In this period, every self-respecting ‘serious’ artist had to have a critical theory. First, Zimmermann rejected traditional opera (almost a cliché), and envisaged the ‘Omnimobil’, interactive theatre where performers confronted the audience, and which integrated architecture, sculpture, painting, spoken and sung theatre, film and television, electronic and concrete music, circus and movement theatre.

Second, Zimmermann proposed a spherical concept of time, where past, present and future co-exist simultaneously rather than in linear sequence. Initially, Zimmermann wanted a dozen separate stages presenting events happening at once; the Cologne Opera rejected that concept as unperformable. In the performed version, Zimmermann settled on three film screens and onstage action to show Marie’s rape.

Soldaten is the aural equivalent of grey sludge: tuneless, dissonant, occasionally cacophonous, and bringing no pleasure to the listener. By this time, music had become mathematical: incredibly geeky arrangements of pitch rows; the LP notes3 elaborate their arrangements over half a dozen pages:

The entire opera is built upon an all-interval twelve-tone row, meaning a series in which all intervals from a semitone (1/2 tone) to a tritone (5½ tones) are present. It is divided into four groups of three tones each. In its original form, the row is as follows:

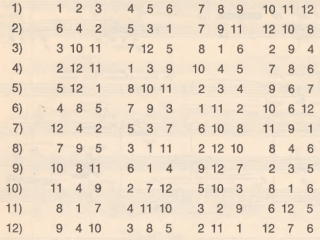

The twelve tones of the scene sequence form the initial tones of twelve fundamental rows, each providing the musical material for the first twelve of the fifteen opera scenes. The fundamental rows are derived through permutation from the all-interval series. Numerically represented, it is as follows:

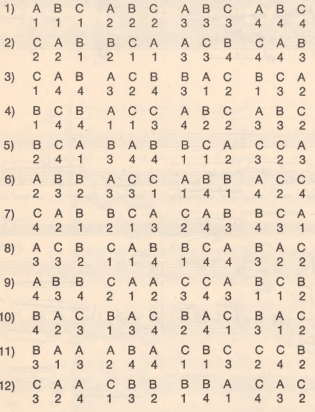

A statistic that demonstrates the affiliation of the individual fundamental row tones to the four groups of three—1, 2, 3, and 4—and also indicates their position within such a group—front (A), middle (B), or back (C)—would yield the following picture:

According to this statistic, relationships can be identified among the twelve fundamental rows, based on both position (A, B, C) and membership in the groups of three (1, 2, 3, 4). Based on positions, the rows 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 10 are related, as they contain three different positions within each group of three. The rows 6, 9, 11, 12 are also related; they use two different positions within each group of three, with one position being duplicated. The rows 4 and 5 are mixed rows, each being half-related to both of the other circles: in one half, they use two positions, while in the other half, they use three positions. Based on their membership in specific groups of three, the following relationships can be observed:

The rows 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11 are related, as they occupy elements from two different groups of three within the all-interval row. The rows 7 and 10 are also related, as they consistently use elements from three different groups of three within the all-interval row. The rows 3, 5, 12 are irregular in this regard.

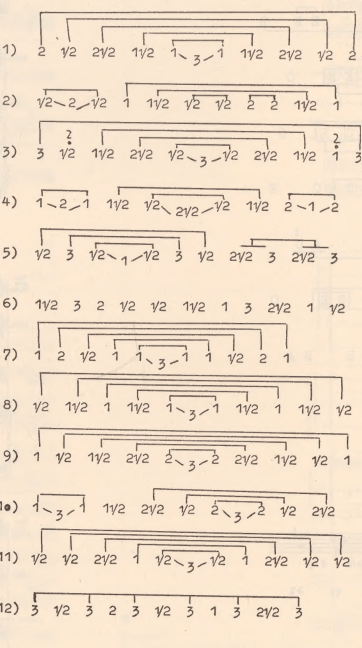

When analyzing the twelve fundamental rows based on their interval structure, the following picture emerges (always measuring the smaller of the known complementary intervals):

From this, it is evident that the rows 1, 7, 8, 9, 11 are structured with exact symmetry. The rows 2, 3, 4, 5, 10 exhibit partial symmetry in certain sections, whereas row 12 is constructed purely additively. In contrast, row 6 is irregular.

Zimmermann derives the four basic forms of the twelve rows by applying the corresponding reflections around the fundamental tone of each respective row to both the “row” and its “retrograde”. If one combines the “row” and its “inversion” into a single system, then…

And so it continues. Because nothing says vital music theatre like rows and inversions. (In other words: get a life!)

The score integrates collages of musical styles: Gregorian chant, mediaeval isorhythmic structures, Bach, and jazz (the Andalusian dance, something musical for a change, reminiscent of Johnny Dankworth’s Avengers theme). To represent different time layers, the orchestra is divided into 13 instrumental groups, playing at different tempi. A 10-speaker system positioned throughout the theatre (onstage, in the audience, and overhead) creates a spatial sound experience: electronic music and tape-recordings of military drill commands, attack sirens, bombings, tanks, and marching steps. “The fragmentary nature of [Zimmermann’s] musical language was an expression of the essential pointlessness of art, the inability for a musical language to express the truth of humanity’s post-war condition.”4

Avant-garde music and art are Germany’s reaction to — revenge for, some might think — losing two world wars. Germany, suffering guilt and intellectual trauma, struggled to process its defeat, so it shattered form and tradition. “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” Theodor Adorno declared. Romanticism was tainted because it belonged to the culture that had produced Hitler (were Beethoven and Wagner responsible for the Third Reich?); lyrical beauty was escapist; tonality and form were rigid and authoritarian; popular art led to conformism and fascism. Atonality, fragmentation, noise and alienation reflect this rupture. But art became self-flagellating, rather than constructive. Germany, rejecting its past, produced music that nobody would want to listen to — formless, dissonant, ugly, unmemorable — and whose composers relied on government sponsorship and (yes) CIA funding. The Darmstadt School imposed an aesthetic of atonalism and alienation, and sneered at the music-loving public who wanted melody, rhythm and orchestral colour — and the public, tired of being told that Mahler was Art Nouveau kitsch and that appreciating avant-garde music made them sophisticated, went elsewhere: to movie scores (which carried on the Romantic tradition), to jazz, to musicals, to pop. And, really, in 1965, why would anyone listen to Die Soldaten when they could listen to The Beatles?

Watch (if you really must):

Bernhard Kontarsky, 1989 Stuttgart.

- Marc Berry, “A Composer of Dark Explosions Turns 100”, New York Times, 16 March 2018. ↩︎

- Bernhard Kontarsky, “Some thoughts about Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten”, Die Soldaten, Teldec 1989, p. 30. ↩︎

- Heinz Josef Herbort “B. A. Zimmermann, Die Soldaten”, Wergo. ↩︎

- Tom Service, “A guide to Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s music”, The Guardian, 26 June 2012. ↩︎

2 thoughts on “295. Die Soldaten (Zimmermann)”