- Tragédie lyrique in a prologue and 5 acts

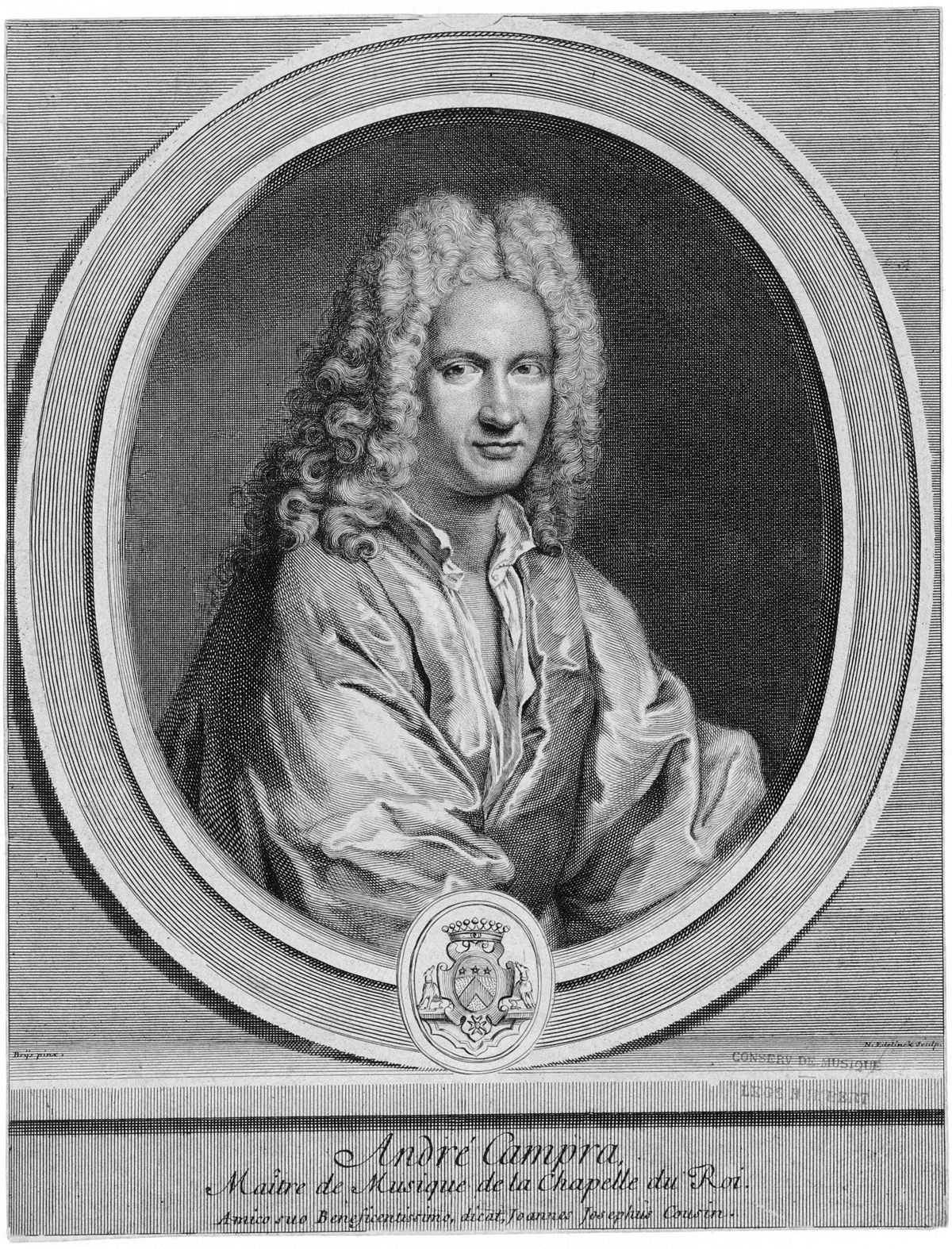

- Composer: André Campra

- Libretto: Antoine Danchet, after Tasso

- First performed: Théâtre du Palais-Royal, Paris, 7 November 1702, conducted by Marin Marais

| Un sage enchanteur [A wise enchanter] | Haute-contre | Jacques Cochereau |

| La paix [Peace] | Soprano | Mlle. Clément L. |

| Suivantes de la paix | Sopranos | Mlle. Clément P. and Loignon |

| TANCRÈDE, a crusader | Bass-baritone | Gabriel-Vincent Thévenard |

| ARGANT | Bass-baritone | Charles Hardouin |

| CLORINDE | Contralto / alto | Julie d’Aubigny (La Maupin) |

| HERMINIE, daughter of the king of Antioch | Soprano | Marie-Louise Desmatins |

| ISMÉNOR, sorcerer | Bass-baritone | Jean Dun père |

| Warrior women | Sopranos | Mlles Dupeyré, Lallemand, and Loignon |

| A sylvan | Haute-contre | Antoine Boutelou |

| A dryad | Sopranos | Mlles Loignon and Bataille |

| A nymph | Soprano | Mlle Dupeyré |

| La vengeance | Tenor (travesti) | Claude Desvoyes |

Welcome to the 18th century!

Campra was the leading French opera composer between Lully and Rameau. A Provençal, he began as a church musician, rising to become chapel master at Notre Dame de Paris.

He made his name with two ballet-operas: L’Europe galante (1697) and Le Carnaval de Venise (1699).

“A musician was born in France, a true dramatic musician,” Pougin proclaimed, “who would be spoken of for more than 30 years, and who occupied the stage until Rameau came as a conqueror.”

These two works are, according to Pougin, light, entertaining, witty, closer to musical comedy than lyric drama. Le Carnaval sounds like it could actually be quite fun: a mixture of commedia dell’arte, plays within plays, and Italian and French styles.

They were published under his brother Joseph’s name. It was an open secret; everyone knew André was the composer, and the Archbishop turned a blind eye, but not a deaf ear.

After the Carnaval‘s smash success, Campra left the cathedral, and dedicated himself to the lyric stage, becoming chief conductor at the Opéra.

His first tragédie lyrique was Hésione (1700), again a success. Campra,

Pougin wrote, replaced the conventional pomp of this rigid stage, the weighty phraseology honoured since Lully, with a style full of warmth, and natural and true characterization. “He introduced movement and life, those two essentials of theatre; he made passion speak; and behind the elegant art of an inspired musician, the spectator felt the heart of a man – and counted, so to speak, its beat.”

The next opera, Aréthuse ou la Vengeance de l’Amour , was a flop; one critic thought the best way to improve it was to lengthen the dances and shorten the dancers’ skirts.

Their next work avenged the failure. It was Tancrède, considered Campra’s masterpiece.

The plot is drawn from Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, also the source of Lully’s best opera, Armide, and a Monteverdi madrigal, Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda – and, a century later, via Voltaire, the work that shot Rossini to stardom.

The crusader Tancrède has captured the Saracen warrior-maiden Clorinde, whom he loves. She also loves him – much to the jealousy of both Herminie, princess of Antioch (who loves Tancrède, even though he invaded her kingdom, and slaughtered her family), and Argant, in love with Clorinde. They lure Tancrède into an enchanted forest with the help of the sorcerer Isménor. Argant challenges Tancrède to mortal combat. Tancrède celebrates his victory – only for the dying Argant to reveal that his opponent was Clorinde, dressed in Argant’s armour. Tancrède goes mad with grief.

The opera was one of the most brilliant and longest successes seen in Paris for a long time. The subject was relatively new – especially, Pougin wrote, for spectators who had for 20 years suffered a monotonous regime of historical or fabulous antiquity. The public were wowed by Jean Berain’s enchanted forests and Isménor’s cavern.

The distribution was something of a stunt: three basses, no tenors, and the first contralto role in French opera – sung by one of the most notorious women of the day.

The armor-bearing Clorinde was sung by Julie d’Aubigny (la Maupin), bisexual cross-dressing swordswoman.

(Yes, there’ve been a TV series and a musical; no comic book as yet.)

La Maupin was some dame. Unhappily married, she eloped with a lover, wanted by authorities for killing a man in an illegal duel. She tired of him, and fell in love with a Marseillaise. When the girl’s parents locked her up in a convent, la Maupin disguised herself, stole an old nun’s corpse, put it in the girl’s bed, and set fire to the room. She was sentenced to death – as a man. And she hadn’t even turned 20 yet. Several affairs later, she found herself in 1690 singing on the Opéra (“the most beautiful voice in the world,” according to the Marquis de Dangeau); kissing girls at balls; fighting duels; and making love to the Elector of Bavaria. You might call her the Lola Montez of her day.

And the opera itself isn’t bad. We’re still very much in tragédie lyrique territory, with all that entails; it may not set the pulse racing like, say, Handel or Gluck do, but it moves swiftly for the genre, with little fat. Recitative – often tedious in Lully, painful in Charpentier – only lasts a minute or so before Campra gives us an aria or an ensemble. His score is more expressive than his predecessors, and demands more virtuosic singing.

Lully’s first acts tended to have the protagonists expositing to their sidekicks. Campra plunges us into the action at once, with the villains plotting revenge. Act I has Argant and Isménor’s duet “Suivons la fureur et la rage”, and ends with a terrific scene where Argant and the Saracen soldiers swear vengeance; the evil wizard Isménor raises up the ghosts of dead kings from their tombs; and heaven sends thunderbolts and earthquakes. It’s less theatrical than Lully’s decorous recitative, but more dramatic – and more operatic.

The centre of the second act is “Quittez vos fers”, Tancrède’s aria releasing the Saracen captives, and the ensemble in praise of Clorinde that follows. Pougin praises its extraordinary theatrical effect and vocal power; “Rameau, even in his finest moments, never conceived anything more vigorous, colourful, or elaborate”. We’ll dispute that when we come to Rameau (listen to, say, Hippolyte et Aricie’s choruses in honour of Hades, Neptune, or Diana, or the giants storming Olympus in Naïs) – but it is a definite highlight. The lyrics, incidentally, are almost identical to “Chantez, célébrez votre reine” in Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide. The duet with chorus, “Si le danger vous étonne”, is exquisite.

In Act III, note Herminie’s plaintive “Cessez, mes yeux, de contraindre vos larmes”, and a charming, dangerously seductive divertissement of dryads and fauns.

Act IV opens with Tancrède’s « Sombres forêts, asile redoubtable”, sung by the knight as he vainly seeks a way out of the magic forest. Pougin praises its poignancy; “impossible to conceive anything finer in this genre”. The act ends with Clorinde’s desolate “Êtes-vous satisfaits, devoir, gloire cruelle”, which, Kaminski says, amounts to a declaration of suicide.

Act V features a marche du triomphe, trumpets well to the fore, and an exultant martial chorus. It ends, unusually for the tragédie lyrique, not with a chorus, but with Tancrède’s dramatic aria, “Elle n’est plus”, the singer’s voice continuing after the final chord.

SUGGESTED RECORDING

Benoit Arnould (Tancrède), Isabelle Druet (Clorinde), Chantal Santon (Herminie), Alain Buet (Argant), Eric Martin-Bonnet (Isménor), with Les Chantres du Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles and Orchestre Les Temps Présents conducted by Olivier Schneebeli. Alpha ALPHA958, 2015.

FURTHER READING

- Vincent Giroud, French Opera: A Short History, Yale University Press, 2010

- Piotr Kaminski, Mille et un opéras, Paris : Fayard, 2003

- Arthur Pougin, introduction to Tancrède: Chefs d’œuvres classiques de l’opéra français, piano/vocal score, Théodore Michaëlis, Paris

2 thoughts on “117. Tancrède (Campra)”