- Opera seria in three acts

- Composer: Francesco Cavalli

- Composed 1667; first performed Teatro San Domenico, Crema, Italy, 27 November 1999

- Librettist unknown

| ELIOGABALO | Countertenor / soprano | |

| ALESSANDRO CESARE | Countertenor / soprano | |

| GIULIANO GORDIO | Countertenor / soprano | |

| FLAVIA GEMMIRA | Soprano | |

| ANICIA ERITREA | Soprano | |

| ATILIA MACRINA | Soprano | |

| LENIA | Tenor | |

| ZOTICO | Contralto | |

| NERBULONE | Bass-baritone | |

| TIFERNE | Bass-baritone | |

| Two CONSULS |

Content warning: “I quote in elegiacs all the crimes of Heliogabalus.”

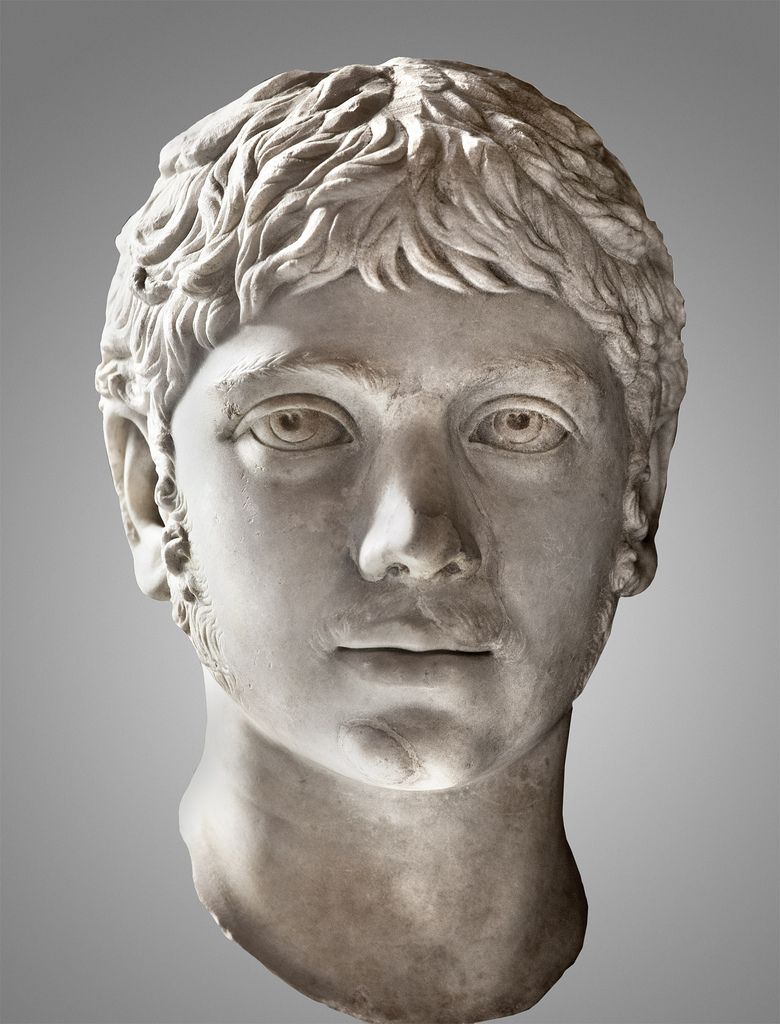

History remembers Heliogabalus (r. 218–222) as one of the very worst Roman emperors.

In all things, the hostile tradition claims, utterly unworthy of the purple.

An effeminate Oriental, swathed in silk, reeking of unguents, offering vast sums to any doctor who could transform him into a woman. A sexual pervert, vicious and depraved, who violated a Vestal Virgin, consorted with spintriae, and to satisfy whose abominable lusts young men were brought from across the empire. A religious fanatic, dancing to cymbals and ‘the thin monotonous whine of accursed flutes’, as he sacrificed children to his phallic god in obscene rituals. His name stinks like the sewer into which his corpse was flung.

Few emperors, in fact, have been so utterly – and perhaps unjustly – condemned as this transgender teenager. He and his mother were murdered by his grandmother and aunt to place his cousin on the throne, and his name was blackened for nearly two millennia.

The principal primary sources for the reign are Cassius Dio, Herodian, and the (now lost) Marius Maximus, all propagandists for his successor, the mother’s boy Severus Alexander. (Dio, for instance, was servant and friend of Maesa, and, under Alexander, twice consul, proconsul of Africa, and governor of Dalmatia and Pannonia Superior. Hardly an objective source.) There is also that hallucinatory forgery, the Historia Augusta, from whence come most of the most salacious details.

Cavalli’s opera adds nothing to our understanding of the emperor. His Eliogabalo is an utterly generic tyrant, indistinguishable from Nero, Domitian, or even Carinus: a hedonist who pursues women, and tries to murder his cousin at a banquet (as Nero poisoned Britannicus) – interrupted by ’owls of dismay.

Eliogabalo was the last surviving work of Cavalli, “the pre-eminent theatre musician of the mid-century” (Carter), the scores of whose almost 30 Venetian operas “shift flexibly between recitative and aria styles, sometimes within only a few bars”.

The opera was composed for the Venice Carnival Season of 1668, but first performed 331 years later. Composed in the austere style of Monteverdi or Lully, it may have been too old-fashioned (not enough arias), or refused for political reasons. Cavalli’s opera ends with the emperor’s assassination; Aurelio Aureli completely rewrote the libretto, perhaps to satisfy the Jesuits. Now, Eliogabalo repents, and rules with his cousin advising him. This version, with a score by one Boretti, was performed throughout Italy for nine years.

Eliogabalo was staged in Paris in 2016 and in the Netherlands in 2017, with the countertenor Franco Fagioli in the title role – a part which displays his acting talents more than his extraordinary voice. His Eliogabalo is poisonous as a cobra, with his cloak trailing behind him like a tail, and the sun-emblazoned disc like a hood. He is also, as the Idle Woman points out, pitiable. When he believes a woman returns his affections, only for her to refuse him, he collapses on the stairs, his cloak wrapped around him to hide his humiliation.

Where, though, is the cult of Elagabal? Where is the black stone of Emesa? Where are his devoted, sensuous mother, his ambitious aunt, and his monstrous granddam? (Absent; instead, three indistinguishable young ladies with whom Eliogabalo is in love, or they with him.) Where, even, are the suffocating rose-petals, or the lions and tigers?

Where, in fact, is Heliogabalus?

Heliogabalus was installed as a puppet by his formidable grandmother Julia Maesa, sister-in-law to the African emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) . Maesa, ‘her mind always turning, always scheming’, claimed that the Syrian youth (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus) was the illegitimate son of the savage Caracalla (r. alone 211–17), Severus’s eldest son. (Varius was probably a cousin, although Hay suggests he may indeed have been Caracalla’s natural son.)

Julia Maesa. Do not cross this woman.

Caracalla’s own life would make a splendid opera. This “common enemy of mankind” (Gibbon) tried to kill his father, and stabbed his brother in his mother’s arms; believed himself the reincarnation of Alexander, and put Alexandria to the sword; and chose lions for his bed-mates. The soldiers, recognising a kindred spirit, loved him – all but one, who slashed at him as he took a slash by the side of the road. Caracalla died unrelieved, unlike the rest of the world.

Macrinus (r. 217–18), a Moorish lawyer, organised the assassination; the Severan forces soon toppled the weak usurper.

Julia Maesa did not expect the youth to be headstrong; she wanted a tool, but the teenager had ideas of his own. With the boy emperor, and his grandmother, came his mother Soaemias, his cousin Severus Alexander and his mother Julia Mamaea … and the black stone of Emesa, sacred to the sun god Ilāh hag-Gabal (Elagabal).

For Heliogabalus was the hereditary high priest of the god. And he tried to make the cult the universal religion of the empire, absorbing the empire’s other gods as Elagabal’s servants or consorts.

The sun-god travelled in a chariot adorned with gold and jewels, drawn by six horses; the emperor ran backward in front of the chariot, facing the god, and holding the reins.

He built a magnificent temple, the Elagabalium, on the Palatine Hill, surrounded by altars. There, every morning, Herodian writes, he would sacrifice hecatombs of bulls and a vast number of sheep. “These he placed upon the altars and heaped up spices of every kind; he also set before the altars many jars of the oldest and finest wines, so that the streams of blood mingled with streams of wine.” (5.5.8)

His face made up, his eyes painted, and his cheeks rouged; dressed in “luxurious” purple robes embroidered with gold, in “effeminate” necklaces and bracelets, and a tiara glittering with gold and jewels, Heliogabalus danced around the altars to the sound of cymbals and flutes – watched by the stupefied senators and knights, traditionalists to a man.

The conservative senator Cassius Dio and the Historia Augusta accuse him of black magic, unholy rites, and sacrificing children (noble, good-looking, and Italian, of course) to his god, inspecting their innards for omens. This is almost certainly a lie; but what else could one expect from a decadent foreigner?

The boy, though, offended Roman religious values by marrying and then divorcing a Vestal Virgin – a crime punishable by stoning, scourging, or burial alive. (This marriage between the priest of the sun and the priestess of Vesta was, apparently, to breed god-like children.) He decided that his god needed a wife – and moved the statue of Pallas into his room: a statue worshipped hidden and unseen, and never moved since it was brought from Troy. So, too, he moved Rome’s most sacred relics into the temple.

Heliogabalus seems to have been an idealist and a visionary, if, as Hay suggests, a neurotic one.

Hay admires the ambition of the emperor’s project; like Elizabeth I, his state church would “replace an independent priesthood which fostered fanaticism, by a race of civil servants who would restrain and modify superstition, turning all dangerous and harmful elements in the religious life into useful and philanthropic energies, concerning whose profit it would take an anchorite to disagree”.

He also condemns its folly; Rome was polytheist, philosophical, rationalist, tolerant, and sceptical – and, at that stage, unreceptive to “the retrograde tendencies of Eastern theistic beliefs”.

“In the long run we know that the mob triumphed, and that every religion of the West was orientalised, every superstition and neurotic tendency developed, and philosophy was brought to its knees utterly debased, until its function was merely to be the apologist of all that superstition taught or did. For the present, rational thinking men were alive. When they died, exclusive monotheism came, carrying before it, like a flood, the greatness of the former world. But the issue was still uncertain…”

Heliogabalus was also gay (possibly bi) – flamboyantly effeminate in a time when men were expected to be macho.

The Romans accepted same-sex relations (with caveats) far more than the West would until the French decriminalised homosexuality in the late 18th century, and the English-speaking world followed in the late 20th. (Of the first twelve Caesars, from Julius to Domitian, only Claudius was entirely heterosexual – and had appalling judgment in wives. Trajan and Hadrian, both ‘good’ emperors, were predominantly homosexual.) What mattered was the virility of the Roman male: he was (in public opinion, at least) penetrator, not penetrated. A cross-dressing pathic emperor scandalised the elite.

Dio describes the emperor’s sexual activities with disgust (doubtless revelling in the propaganda). “He drifted into all the most shameful, lawless, and cruel practices, with the result that some of them, never before known to be in Rome, came to have the authority of tradition, while others, that had been attempted by various men at different times, flourished merely for the three years, nine months and four days during which he reigned.”

According to the histories, his agents scoured bath-houses across the empire for the most well-endowed men. Dio says the boy went to taverns in drag as a female huckster; he drove the prostitutes out of the brothels, and whored himself there. “Finally, he set aside a room in the palace and there committed his indecencies, always standing nude at the door of the room, as the harlots do, and shaking the curtain which hung from gold rings, while in a soft and melting voice he solicited the passers-by” (LXXX.13).

More, Heliogabalus was probably transsexual. He circumcised himself (as part of his priestly requirements), Dio wrote, and planned to cut off his genitals altogether, “a desire … prompted solely by his effeminacy”. He wanted the doctors to contrive a woman’s vagina in his body by means of an incision. He (she?) married Hierocles, a Carian slave, and was termed wife, mistress, and queen. He (she?) would be caught in adultery (“to imitate the most lewd woman”), and his (her?) husband would beat him (her?). He (she?) wore women’s clothing when at the Senate or meeting foreign ambassadors; and insisted: “Call me not Lord, for I am a Lady.”

Julia Maesa, his repellent grandmother, and Julia Mamaea, his aunt, spurred the Praetorian Guard to murder him, and placed his malleable cousin Severus Alexander on the throne. The soldiers killed the emperor and his mother – in a latrine, according to some sources. Their heads were cut off; the bodies were dragged through the city, and mutilated by the crowd [1], before they were flung into the public sewer. His memory was condemned, his statues effaced, and for centuries his name has been a hissing and a byword.

“Instead of the generous, fearless, affectionate boy whom the populace had known,” Hay wrote, “there emerged the sceptered butcher ill with satyriasis; the taciturn tyrant, hideous and debauched, the unclean priest, devising in the crypts of a palace infamies so monstrous that to describe them new words had to be coined. It was Mamaea’s work, and for 1800 years no one has had the audacity to look below the surface and unmask the deception.”

(Severus was later assassinated by Maximinus Thrax, an enormous pheasant. This was the start of the Third Century Crisis.)

By the time of the Historia Augusta (a single late 4th century author claiming to be six people a century earlier), depictions of Heliogabalus have become pure fantasy. “Aelius Lampridius’s” Heliogabalus is a decadent hedonist out of Baudelaire or Wilde.

He lies on silver couches with gold coverlets, eating camels’ heels and cocks’ combs taken from living birds, the tongues of peacocks and nightingales, fondling perverts while his guests suffocate under falling rose petals, or chew dinners of glass and paint.

Lions, leopards, and bears prowl the corridors of his palace; he builds mountains of snow in his garden, or collects cobwebs from around the empire. He amuses himself with his organ (hydraulic); sinks ships in the harbor; or drives chariots pulled by tigers, stags, or elephants. He invents Babylonian lotteries where the prizes range from mansions to dead dogs; to his friends, he sends frogs and scorpions, snakes and flies. He empties his bowels in a golden vessel, and urinates in vessels of murra or onyx. And, of course, he practices black magic and human sacrifice.

“It may seem probable, the vices and follies of Elagabalus have been adorned by fancy, and blackened by prejudice,” Gibbon wrote. “Yet confining ourselves to the public scenes displayed before the Roman people, and attested by grave and contemporary historians, their inexpressible infamy surpasses that of any other age or country.”

It was not until the early 20th century that a different picture of the emperor began to emerge. John Stuart Hay (The Amazing Emperor Heliogabalus, 1911) argues that he was a psycho-sexual hermaphrodite, good-hearted, who wanted to unify the Roman Empire through a single religion (a task the despicable Constantine would execute).

Alfred Duggan’s Family Favourites (1960) also presents Heliogabalus in a sympathetic light. (It’s been years since I read it; don’t ask for details.) So does Nigel Barnes’ psychohistory Blood Mingled with Wine (2018). His Freudian reading suggests Heliogabalus was an affectionate, sensitive, intelligent, and pious teen, more child than adult, predominantly female, and grappling with his same-sex desires.

“Heliogabalus had done little to deserve such censure. His real crime was to offend the sensibilities of his time.”

Modern gay culture, Barnes points out, has reclaimed Heliogabalus as an icon, a martyr, “a boy who bravely flaunted his sexuality and stood alone against the prejudices of the macho regime of the time”.

Nothing of the emperor’s religious vision, nothing of the power struggle with his grandmother and aunt, little of his sexuality make it into Cavalli’s opera.

The plot is semi-fictional; so are the characters. The praetorian prefect is one Giuliano Gordio. Who? The historical Ulpius Julianus was prefect under Macrinus; defeated in battle by the Severans, his severed head was sent to the emperor. Are we meant to think of the short-lived Gordian dynasty, father and son who ruled for three weeks 16 years later, or the grandson who ruled for six years? Surely knot.

The emperor’s crony is Zotico, based on Heliogabalus’s corrupt minister and husband found in the Historia Augusta. Dio, in a better position to know, records that Aurelius Zoticus, a native of Smyrna, was an attractive, extremely well-endowed athlete who met the emperor only for one disappointing night.

Hearing that Zoticus’s private parts were greatly bigger than anyone else’s, the emperor summoned him to Rome, accompanied by an immense escort. He was appointed cubicularius; honoured by the name of the emperor’s grandfather, Avitus; and adorned with garlands as at a festival – all before the emperor had even seen him.

The jealous Hierocles gave him a drug “that abated the other’s manly prowess. And so Zoticus, after a whole night of embarrassment, being unable to secure an erection, was deprived of all the honours that he had received, and was driven out of the palace, out of Rome, and later out of the rest of Italy; and this saved his life.”

Déodat de Séverac’s Héliogabale (1910), praised in its day, seems to be a version on Quo Vadis?.

[1] Hay maintains that Heliogabalus was always popular; this outrage was the work of his aunt. “To account for the treatment of Antonine’s body at the hands of the mob is certainly difficult. We know that he had done nothing which could have rendered him obnoxious to the populace. To ascribe it to intolerance of his psychopathic [sic] condition shows, not only ignorance of Roman susceptibilities but also a foolish antedating of popular prejudice. … The probable solution lies in the fact that Mamaea’s money, which had caused the murder, invented this scheme for disgracing her nephew’s memory, and thus averted trouble from herself. It would raise a popular tumult, or at any rate a disgust for the idol of the masses, if they could have Antonine’s body dragged through the city publicly, as the perpetrator of unmentionable crimes, concerning which the populace knew nothing. Suffice it to say that it did the work. Antonine had the stigma of all crimes imputed to his memory; and Alexander the good arose superior to all human frailties. Then and not till then, Rome began to be shocked.”

Works consulted

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, trans. Ernest Cary, 1927

<http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/80*.html> - Herodian, Roman History, trans. Edward C. Echols, 1961 <https://www.livius.org/sources/content/herodian-s-roman-history/>

- Lives of the Later Casears: The first part of the Augustan History, with newly compiled Lives of Nerva and Trajan, trans. Anthony Birley, Penguin Books, 1976

- Nigel Barnes, Blood Mingled with Wine: The Life of the Emperor Heliogabalus, 2018

- Mauro Calcagno, “‘Eliogabalo’ by Francesco Cavalli in Dortmund”, [t]akte, February 2010

< https://www.takte-online.de/en/music-theatre/detail/artikel/eliogabalo-von-francesco-cavalli-in-dortmund/index.htm> - Tim Carter, “The Seventeenth Century”, in The Oxford History of Opera, ed. Roger Parker, Oxford University Press, 1996

- John Stuart Hay, The Amazing Emperor Heliogabalus, Macmillan, 1911

- John Warrack & Ewan West, The Oxford Dictionary of Opera, 1997

The author is mildly obsessed with Ancient Greece and Rome. He spent his childhood reading mythology, half-believing in the gods and heroes, and drawing and acting out scenes, and from his adolescence and university years reading biographies of the Roman emperors.

His favourite cookbook since middle school is The Roman Cookery of Apicius (translated and adapted for the modern kitchen by John Edwards). He carries replica imperial coins in his wallet as a charm; and he developed an unfortunate twitch after watching I, Claudius. He has been known to wander round the Louvre, greeting imperial busts as old friends.

He occasionally believes civilization has declined since the second century AD. (This may explain why he often reckons from 27 BC, the accession of the Divine Augustus.) He has contemplated becoming a Hellenic neo-paganist.

He feels one of life’s greatest tragedies is that only one percent of ancient literature has survived. He would like to read all Greek tragedy, from Agathon to Xenocles, or enjoy such noble, uplifting works as Suetonius’s Lives of Famous Whores, Physical Defects of Mankind, and Greek Terms of Abuse.

His dramatic monologue, The Death of Domitian, was performed at Monash University, Melbourne, in 2012.

He has also just discovered that he can legally change his name for a mere couple of hundred dollars. His given name means ‘Victory of the people’; this, he deems, is not magnificent enough. ‘Caesar’ would be a better name, or possibly he should rename himself after one of the emperors he most admires. Until then, he will answer only to Dominus et Deus.

One day, he would like to actually learn Greek and Latin.

And I’ve just acquired a denarius of Heliogabalus! (If it were an as, I could have said this old coin is an as-been.)