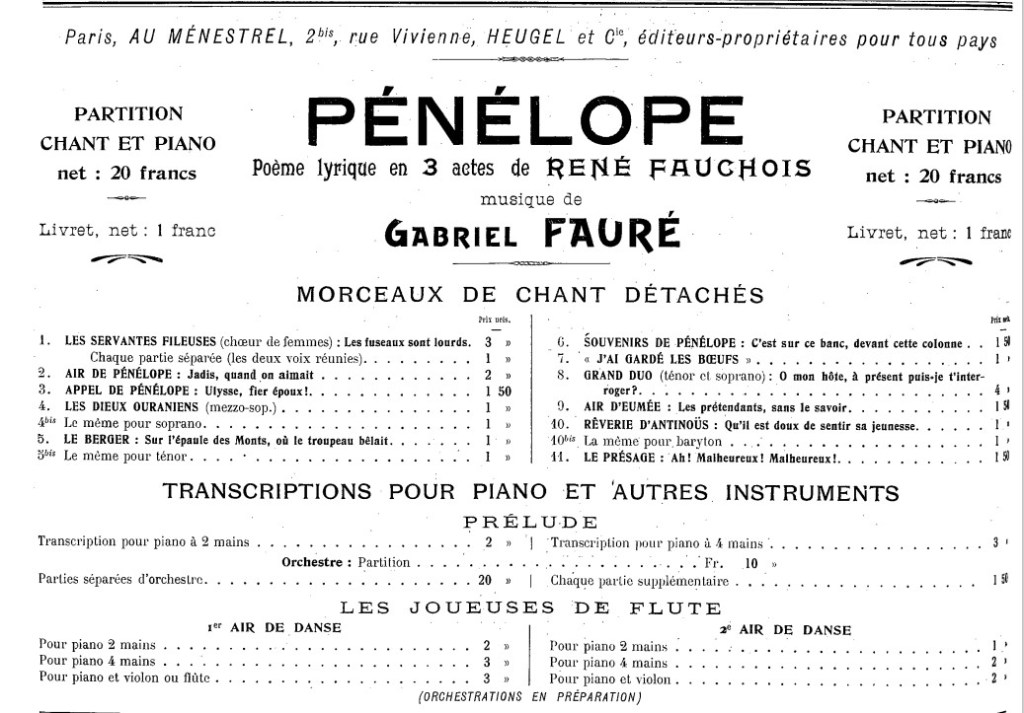

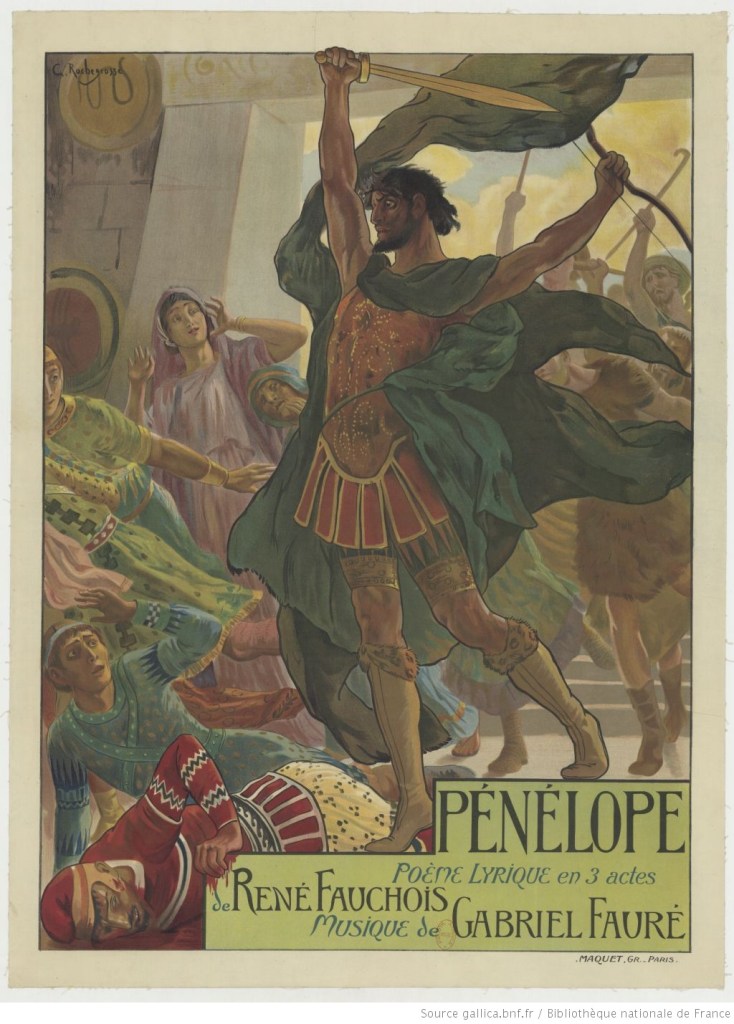

- Poème lyrique in 3 acts

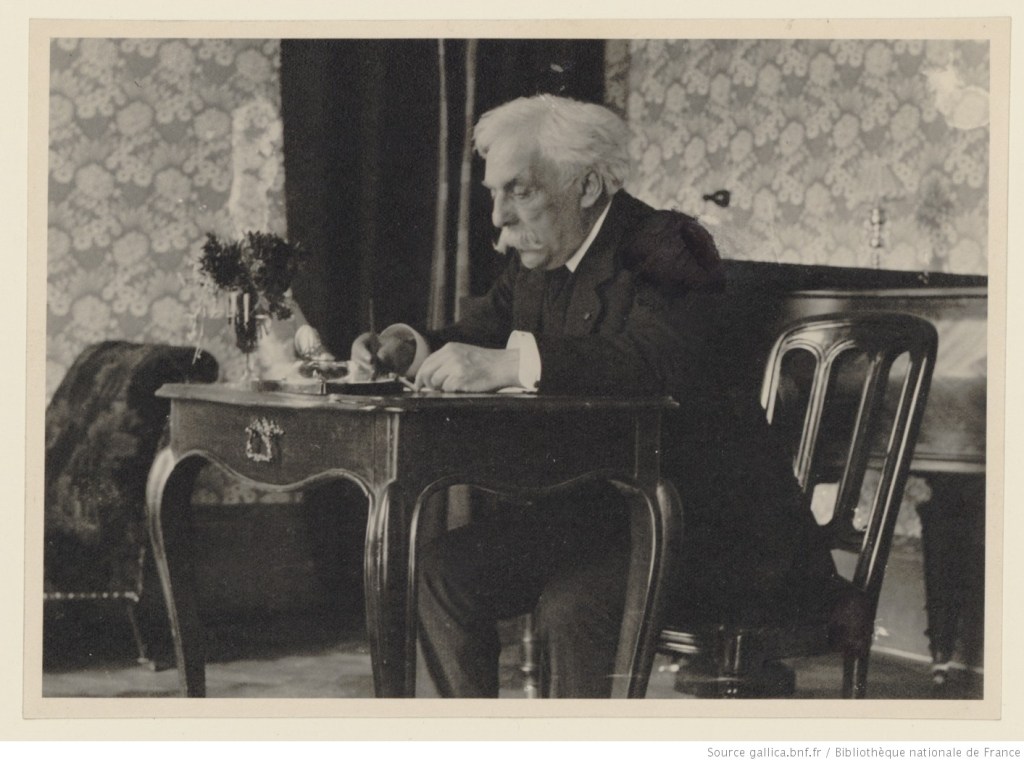

- Composer : Gabriel Fauré

- Libretto : René Fauchois

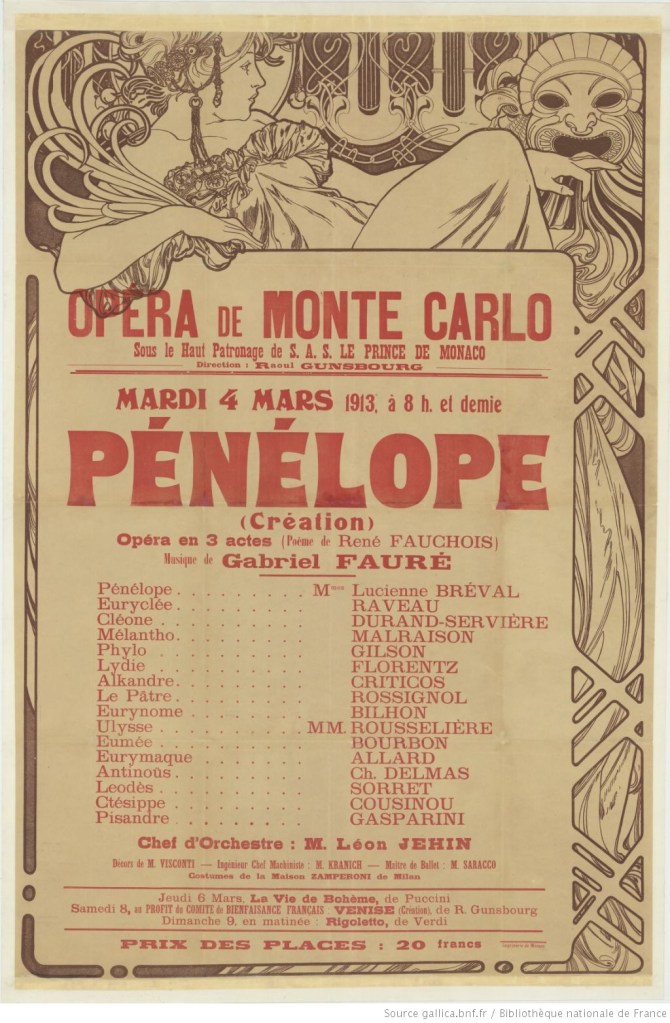

- First performed: Opéra de Monte-Carlo, 4 March 1913, conducted by Raoul Gunsbourg

- First Parisian performance: Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, 10 May 1913, conducted by Gabriel Astruc

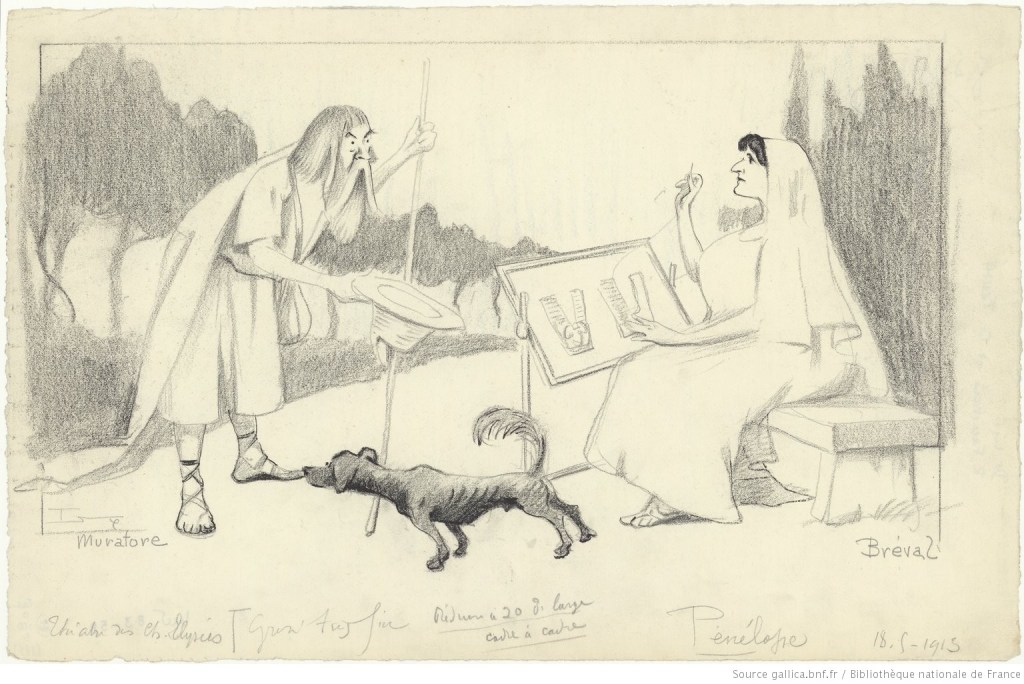

| ULYSSE, king of Ithaca | Tenor | Charles Rousselière |

| EUMÉE, an old shepherd | Baritone | Jean Bourbon |

| ANTINOÜS, suitor | Tenor | Charles Delmas |

| EURYMAQUE, suitor | Baritone | André Allard |

| LÉODÈS, suitor | Tenor | Sardet |

| CTÉSIPPE, suitor | Baritone | Robert Couzinou |

| PISANDRE, suitor | Sorret | |

| A Shepherd | Rossignol | |

| PÉNÉLOPE, queen of Ithaca | Soprano | Lucienne Bréval |

| EURYCLÉE, nurse | Mezzo | Alice Raveau |

| CLÉONE, servant | Soprano | Durand-Servièré |

| MÉLANTHO, servant | Mezzo | Cécile Malraison |

| ALKANDRE, servant | Soprano | Criticos |

| PHYLO, servant | Soprano | Gabrielle Gilson |

| LYDIE, servant | Soprano | Florentz |

| EURYNOME, housekeeper | Rozier | |

| Shepherds, Servants, Dancers and Flute-players |

SETTING: Ithaca, 10 years after the Fall of Troy.

Heureux celui qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage…

Joachim du Bellay, 1558

Gabriel Fauré’s only opera [FN 1], Pénélope tells the same Homeric story as Monteverdi’s Ritorno di Ulisse in patria (1640).

Faithful Pénélope has waited 20 years for her husband, Ulysse (Odysseus), to return from the Trojan Wars, while keeping suitors at bay. She claims that she cannot marry any of them until she has made the shroud for her father-in-law; she sews by day, and unpicks the shroud at night. But the suitors have seen through that ruse, and demand that she marry one of them the next day. Pénélope protests that she will only marry the man who can draw Ulysse’s mighty bow – a task none of the suitors can achieve. But Ulysse, disguised as a vagabond, has returned to Ithaca; he seizes the bow, and shoots the suitors dead.

[1] He had written stage music for plays by Dumas, Shakespeare, and even Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande, while a grand cantata, Prométhée, was performed, like Saint-Saëns’s Déjanire and Séverac’s Héliogabale, at the Arènes de Béziers, in 1900. Prométhée was later revised and performed at the Paris Opéra in 1917.

Pénélope, a striking work of post-Wagnerian Classicism, is both conservative and innovative – traditional enough to please Arthur Pougin, who welcomed the return to the fundamental principles of music after the aberrations of the modern school (presumably Schoenberg and co.), and modern enough for Nadia Boulanger, 50 years his junior, to admire the novelty of the writing and the unusual harmonies.

Like most French operas of its time, Pénélope is through-composed, divided into scenes, and uses leitmotifs. (Various arias were, however, sold separately as piano / vocal pieces.)

But it feels more like Saint-Saëns, its dedicatee, than Wagner. In some ways, it is a superior version of Hélène (1904); the two works bookend the Trojan Wars, and focus on the tribulations of a couple.

Fauré’s score is restrained, reserved. It is a beautiful work, but not one with much action, or vocal display and Big Tunes.

“Little noise, few outbursts … disdainful of all commonplaces, it is with emotion and sincerity alone that M. Fauré hopes to move us,” Boulanger wrote. Likewise, Pougin described the libretto as “serious without austerity, simple, sober, well-conceived, without superfluous incidents, and above all deriving its value from the colour and character which the author gave it without ever falling into overemphasis and grandiloquence”.

Perhaps that is why it is seldom performed. Aaron Copland, for one, complained that it was “distinctly non-theatrical” – and that reputation has dogged it, rather. But on audio, it works marvellously; one can appreciate the delineation of character, the setting of the text, and the quiet intensity of the score.

The opera begins with a rather pensive prelude, featuring many of the motifs of the opera.

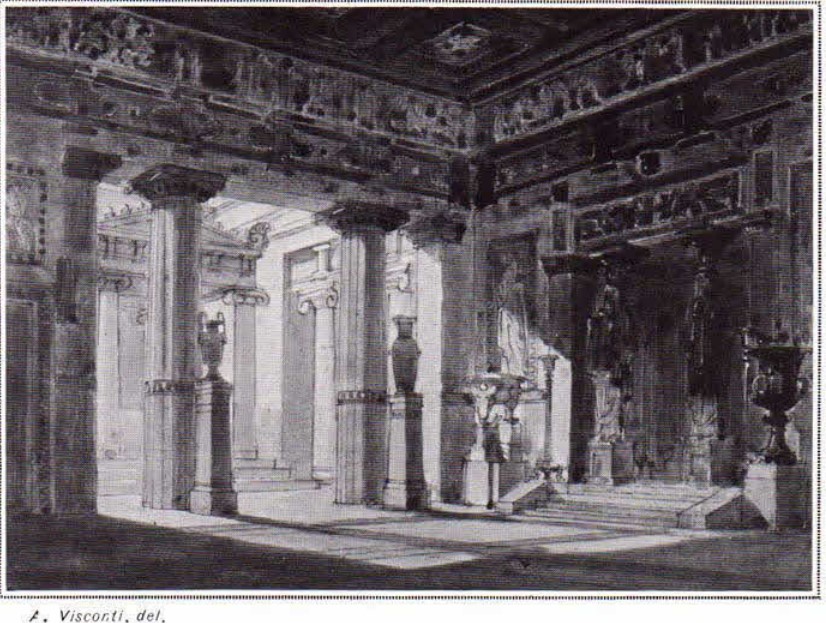

Act I takes place inside the palace at Ithaca, and depicts Ulysse’s return (as yet unrecognised by his wife). There is a serene, rather antique dance of flute players, accompanied also by harps, triangles, and tambourines. Louis Schneider called it “a musical jewel that creates the pagan ambience of the work”. Pénélope expresses her desire for her absent husband in the aria « Vous n’avez fait qu’éveiller dans mon sein » (L’Appel de Pénélope), tinted with regret and delicate eroticism. In a phrase full of mystery, “Les Dieux ouraniens”, she suggests that vagabonds could be gods in disguise. Nadia Boulanger was struck by the “strange and novel sonority” – an almost Impressionist descending phrase on flute and harps – when Pénélope unpicks the shroud, watched by the suitors. The one forceful utterance in the act is Ulysse’s exclamation at the end: “Épouse chérie!”

Act II takes place on a hillside overlooking the sea; here Pénélope comes every evening to watch for her husband. In the Souvenirs de Pénélope (« C’est sur ce banc, devant cette colonne »), she remembers being with her husband. The act ends with Ulysse revealing himself to the shepherds.

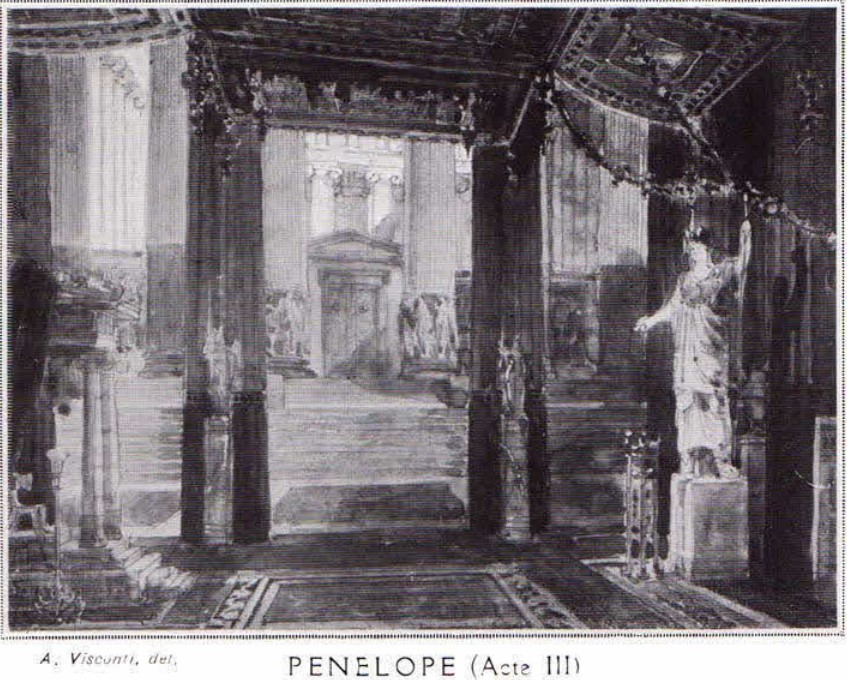

Act III takes place in the banqueting hall, where Pénélope is supposed to choose which suitor she will wed. One of the suitors, Antinous, woos her in the honeyed « Reine, dissipe le chagrin qui pâlit ton beau front » (the Rêverie). Pénélope’s prophetic vision of the suitors’ impending deaths (le Présage: « Ah! Malheureux ! ») is striking. So, too, are the Wagnerian orchestral flourishes when Ulysse bends the bow. The opera ends with a triumphant C major finale, husband and wife reunited, and general rejoicing that the king has returned.

Pénélope was first performed in Monte Carlo, in March 1912, then in Paris two months later. On both occasions, it was a critical success.

Boulanger (Le Ménestrel) called it “one of the most noble, worthiest, and most moving” scores there was, while Paul Milliet (Le Monde artiste) declared it was one of the strongest and most beautiful works he had ever heard. “The nobility of the ideas, the distinction of the harmonies, the richness of the modulations, the splendour of the orchestration made it a masterpiece of pure music.” Likewise, Louis Schneider (Annales politiques et littéraires) wrote: “I believe that the score of Pénélope, with its compact writing, its brilliantly written counterpoint, and its eloquent and distinguished solemnity, will remain a model. It is the most refined art. It will be a treat for all those with fine taste.”

Critics felt Fauré’s approach was truly Classical. Schneider compared his exquisite purity and sense of proportion to the harmonious architecture of Attica, or to Ernest Renan’s Prière sur l’Acropole. Similarly, Pougin felt that “an Attic breeze” had passed over the score; it was sometimes harsh, sometimes calm, sometimes graceful, but there was always an exquisite feeling of serenity.

Three weeks later, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring revolutionised music. The next year, World War I broke out, and the Belle Époque ended.

Recordings

Listen to: Jessye Norman (Hélène), Alain Vanzo (Ulysse), José van Dam (Eumée), and Michèle Command (Euryclée), with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte Carlo, conducted by Charles Dutoit. Erato, 1982.

Works consulted

- Louis Schneider, Les Annales politiques et littéraires, 9 March 1913

- Nadia Boulanger, Le Ménestrel, 15 March 1913

- Arthur Pougin, Le Ménestrel, 17 May 1913

- Paul Milliet, Le Monde artiste, 17 May 1913

- Read also Phil’s Opera World

I tried to give this a listen mainly because I’m a huge Jessye Norman fan but I found it to be another snoozer. I was baking while listening to it and nearly fell asleep in my muffin batter.

LikeLike

Well, French operas of the early 20th century (Massenet aside) do tend to be ultra-refined.

LikeLike