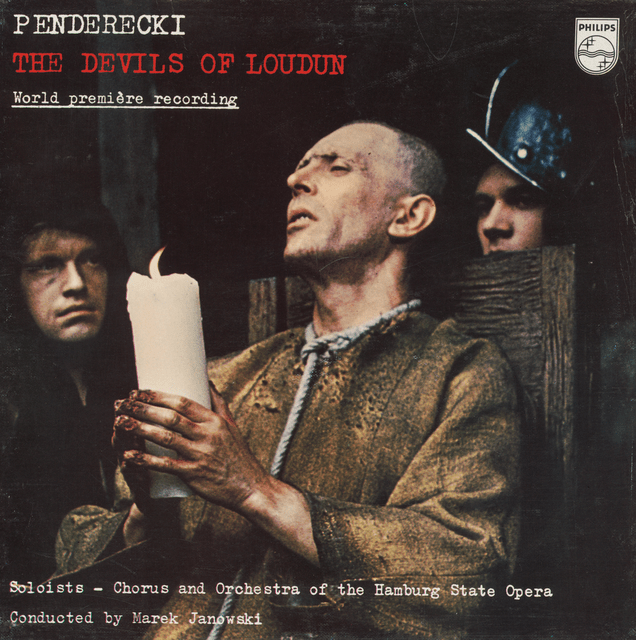

- Opera in 3 acts

- Composer: Krzysztof Penderecki

- Libretto: Based on John Whiting’s dramatisation of Aldous Huxley’s The Devils of Loudun (1952), in the German translation of Erich Fried

- First performed: Hamburgische Staasoper, Hamburg, Germany, 20th June 1969

Characters

| JEANNE, Prioress of the Ursuline Convent | Dramatic soprano | Tatiana Troyanos |

| CLAIRE LOUISE GABRIELLE, Ursuline sisters | Mezzo Mezzo Soprano | Cvetka Ahlin Ursula Boese Helga Thieme |

| PHILIPPE TRINCANT, a young girl | High lyric soprano | Ingeborg Krüger |

| NINON, a young widow | Contralto | Elisabeth Steiner |

| URBAIN GRANDIER, Priest of St. Peter’s | Baritone | Andrzej Hiolsky |

| VATER BARRÉ, Vicar of Chinon | Bass | Bernard Ładysz |

| VATER RANGIER | Basso profundo | Hans Sotin |

| VATER MIGNON, Father-confessor to the Ursulines | Tenor | Horst Wilhelm |

| VATER AMBROSE, an old priest | Bass | Ernst Wiemann |

| JEAN D’ARMAGNAC, Mayor | Speaking part | Joachim Hess |

| GUILLEAUME DE CERISAY, Town judge | Speaking part | Rolf Mamero |

| ADAM, apothecary | Tenor | Kurt Marschner |

| MANNOURY, surgeon | Baritone | Heinz Blankenburg |

| BARON DE LAUBARDEMONT, the King’s Commissioner | Tenor | Helmut Melchert |

| PRINZ HENRI DE CONDÉ, the King’s Ambassador | Baritone | William Workman |

| BONTEMPS, a gaoler | Bass-baritone | Carl Schulz |

| Clerk of the Court | Speaking part | Franz-Rudolf Eckhardt |

| ASMODEUS | Bass | Arnold van Mill |

| Ursuline nuns, Carmelites, people, children, guards, soldiers |

SETTING: Loudun, France, 1634

In seventeenth-century Loudun, as in the last war, and still at the present time, we encounter intolerance, cruelty, and the constant menace to the individual which comes from bigotry, fanaticism, and organised hatred. The Devils of Loudun expounds a highly charged, timeless theme, set in an historical framework. For Krzysztof Penderecki, a Pole and a sincere Catholic, who in his boyhood witnessed the show trials of Stalin, this material has great present-day application.

A. David Hogarth, 1969 Philips

In 1632, Ursuline nuns at the convent of Loudun claimed they were possessed by demons. Led by the prioress, Jeanne des Anges, they accused the local priest, the libertine Urbain Grandier, of ensorcelling them. Although Grandier was acquitted, he was later tried again, at the orders of Cardinal Richelieu, his enemy; he was found guilty, put to the Question, and then burnt at the stake.

In 1952, Aldous Huxley wrote up the matter as an intriguing case of sexual hysteria. In his reading, the prioress was sexually attracted to Grandier; she took his refusal to become the nuns’ spiritual director as an insult, and her love turned to hatred. His novel was later adapted as a play (1960), which in turn became the source of Penderecki’s opera, commissioned by the Hamburg Opera. But the most famous version is Ken Russell’s controversial film (1971), with Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave.

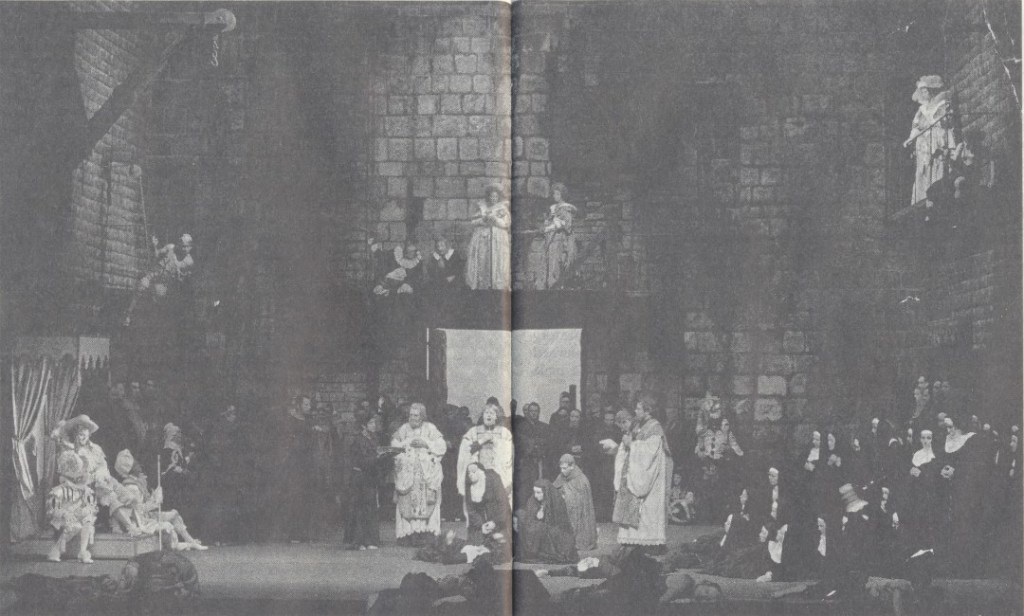

Die Teufel von Loudun is not an enjoyable opera, but it is a powerful one. This is late 20th century opera, atonal and expressionist, the work of an avant-garde composer; it goes almost without saying that that there are no ‘tunes’. Instead, the music serves the drama. The opera’s 30 scenes incorporate recitative, speech, Gregorian chants, and ensembles. The music comprises, in Bernard Jacobson’s words, “dense tone clusters, eerie glissandos, slow, wide vibratos, cluckings and brayings of woodwind and brass”, and a large orchestra, including contemporary instruments like the electric guitar.

But it is not for the squeamish; it is grotesque and often violent. Nuns masturbate, or writhe in orgies; Breughelian beggars and cripples hobble about the stage; enemas are forcibly administered; and condemned men have their fingernails torn out and their bones shattered. It is an indictment of the barbarity and superstition of the early modern period, when people believed in demons, and tortured people to death to save their souls.

It also depicts the individual resisting the oppressive power of the state – as noble in 17th century France as in Penderecki’s homeland of Poland, then under Communist occupation. On his procession to the funeral pyre, the maimed Grandier attains Christ-like dimensions: while he is a womaniser, and has broken his priestly vows, he is innocent of the crime of which he has been accused. Grandier dies, but he dies with integrity, refusing to make a false confession, to ease his torment at the cost of the truth. The composer himself compared the opera (or, as he saw it, quasi-oratorio) to his earlier St. Luke Passion. “Both are about a trial, in the broadest sense of the word – a via crucis.”

That final act (the trial and execution) is by far the strongest of the three. It works as theatre, at the very least. Nevertheless, Teufel has never been popular. Many critics complained the music was boring and lacked originality; they even called it an ‘anti-opera’, or pelted the stage with fruit. Warrack and West, for instance, thought “the effects are not always backed with sufficient musical substance and continuity”; and The Gramophone found it “dispiriting”, “the occasional accumulations of dense choral and orchestral textures … seem like more sound effects grafted on for the sake of a little variety”. But it also has its fervent admirers. Frank Zappa, however, listed it as one of his 10 favourite scores (he particularly enjoyed the enema scene), and the music later ended up in The Exorcist.

The 1969 telefilm makes a strong case for the work. But be prepared for adult themes, and approach it more as sung theatre than as opera.

Recordings

Listen to: Original cast recording, conducted by Marek Janowski, Hamburg, 1969. Philips.

Watch: Original cast, directed by Marek Janowski, Supraphon, 1969.

Works consulted

- A. David Hogarth, notes to world premiere recording, Philips 1969

- Jack Hiemenz, “A Composer Praises God as One Who Lives in Darkness”, New York Times, 27th February 1977

- Bernard Jacobson, “Dramatic Work with Religious Theme”, Philips 1995

- Arnold Whittall, “Penderecki Die Teufel von Loudun“, The Gramophone, June 1996

- John Warrack & Ewan West, The Oxford Dictionary of Opera, 1997

- Piotr Kaminski, Mille et un opéras, Paris : Fayard, 2003

- “The Devils of Loudun (opera)”, Wikipedia

When you said that this opera is not for the squeamish, you couldn’t be more right about that! I’m very squeamish. I get upset by violence. And scared by the demonic stuff (The movie The Exorcist scares the living daylights out of me. But I still love to watch it. I just can’t watch it alone and can’t be alone for the rest of day and night afterwards! Yeah, I’m a )pu$$y.

This opera, I did skip through the Youtube video of it and every thing that I saw was too disturbing for me. Particularly the scene of the feet hanging down from the upper frame. I thought maybe I’d just listen to it without watching it but even the music scares me!

So I’m going to move on to one of your other obscure operas that won’t scare me.

LikeLike