- Opéra in 4 acts

- Composer: Louise Bertin

- Libretto: Victor Hugo, after his novel Notre-Dame de Paris (1831)

- First performed: 14 November 1836

Characters

| LA ESMERALDA, a gypsy | Soprano | Cornélie Falcon |

| PHŒBUS de CHÂTEAUPERS | Tenor | Adolphe Nourrit |

| CLAUDE FROLLO | Bass | Nicolas Levasseur |

| QUASIMODO, bellringer of Notre-Dame | Tenor | Jean-Étienne-Auguste Massol |

| FLEUR-DE-LIS | Soprano | Constance Jawureck |

| MADAME ALOÏSE DE GONDELAURIER | Mezzo | Augusta Mori-Gosselin |

| Diane | Mezzo | Mme. Lorotte |

| Bérangère | Mezzo | Mme. Laurent |

| Le Vicomte de Gif | Ténor | Alexis Dupont |

| M. de Chevreuse | Bass | Ferdinand Prévôt |

| M. de Morlaix | Bass | Jean-Jacques-Émile Serda |

| CLOPIN TROUILLEFOU | Tenor | François Wartel |

| The Town Crier | Baritone | Hens |

| People, Truands (Hoodlums), Archers, etc. |

Setting: Paris, 1482

Victor Hugo’s preface to his only opera libretto, an adaptation of his great novel Notre-Dame de Paris (better known to Anglophones as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame), is rather apologetic:

If, by chance, someone recalls a novel while listening to an opera, the author feels compelled to inform the public that to bring something of the drama that serves as the foundation for the work entitled Notre-Dame de Paris into the distinctive perspective of the lyrical stage, various modifications were deemed essential, sometimes to the story, sometimes to the characters. The character of Phœbus de Châteaupers, for instance, is one of those that had to be altered; a different dénouement was required, and so forth. Moreover, although, even in writing this little work, the author has strayed as little as possible, only when the music demanded it, from certain conditions that he deems indispensable to any work, small or great, he intends to offer here to the readers, or more precisely to the listeners, nothing more than a libretto for an opera, more or less well arranged for the musical work to harmoniously overlay it – a pure and simple libretto… It is only a framework, which is eager to disappear under the rich and dazzling embroidery known as music.

Notre-Dame de Paris was a rather awkward choice for an opera adaptation. The story would indeed make a splendid libretto: it has obsession and passion, innocents suffer, and nearly all the characters die. But the story does not begin until halfway through. Written to advocate for the preservation of the great Paris cathedral, neglected at the time, character and plot are, for the most part, secondary to the architecture and the historical reconstruction of late 15th century Paris. But it is magnificent all the same – grim, yes, but rich in colour and incident. There are stirring and picturesque scenes (the Feast of Fools, the Cour des Miracles), scenes that wring the heart (the ordeal of Esmeralda, the recognition scene in the Sachette’s cell), and superb descriptions (Quasimodo and his bells). When I read it for the first time, some 17 years ago now, I thought it one of the finest things I had ever read. As Casimir Delavigne1 wrote: “M. Hugo has erected an immense literary edifice, beneath the gates of which the greatest among them will be able to pass without stooping; and posterity … will say Hugo, as they say Dante and Shakespeare, Corneille and Byron.”

Hugo jettisons scenes, characters, and themes like so much unnecessary baggage. Gone is the magisterial evocation of the age, encompassing an entire society from the king and courtiers at the top to the beggars and the Cour des Miracles at the bottom. Gone are many of the characters: the playwright Gringoire (Hugo’s stand-in); Frollo’s wastrel brother Jehan; the Sachette, and the subplot of the missing child; and the goat Djali. (It would finally trot the opera stage some 20 years later in the guise of Dinorah’s Bellah, in Meyerbeer’s Pardon de Ploërmel, 1859.) Those characters who remain are, as Hugo wrote, modified. Phœbus de Châteaupers, in the novel a handsome cad, a would-be rapist, and a thoroughgoing rotter who lets Esmeralda hang, becomes the opera’s romantic lead, gallant and sympathetic. Frollo (now an alderman; the censors demanded that he no longer be a priest) becomes a standard “heavy”; he is not the tormented archdeacon, austere, celibate, and humourless, who longs to be a good man, but whose sexual frustration makes him a monster, destroying Esmeralda to end his desire for her. Gone are scenes that would have made a fine impression: e.g., Esmeralda’s trial and torture; the recognition scene. (The siege of the cathedral and the battle in the parvis might have taxed even the Opéra’s resources, however!) Gone are the moral themes: the shallow handsomeness of Phœbus contrasted with the ugly devotion of Quasimodo, Esmeralda’s immature and ungrateful preference for the former, and the mob’s prejudice towards gypsies and Quasimodo. Gone is the intellectual theme: “This will kill that”, printing and the book replacing architecture.

La Esmeralda is, frankly, an opera about not very much in particular. As L’Indépendant2 commented, “the libretto offers only a pale, faded copy” of the original. Like so many Italian operas, it is a standard love triangle: the bass thwarts the love of the soprano and tenor, and they die at the end. Much of it feels like picturesque scenes from the novel, set to music. While there is incident, there is little drama – astonishingly for Hugo, the greatest dramatist of his age. (Anyone who doubts that should read or watch the final scene of Marie Tudor.) A magnificent opera could have been made of Notre-Dame de Paris; disappointingly, this isn’t it. And yet Scribe’s libretti for Meyerbeer and Halévy (Les Huguenots and La Juive in particular) had shown that grand opéra could do justice to sublime themes.

The saving grace of the opera is that “rich and dazzling embroidery known as music”. The composer was Louise Bertin (1805–77), invalid daughter of the founding director and sister of the editor-in-chief of the pro-royalist Journal des Débats.

“The extraordinary success of Notre-Dame,” Hugo’s widow Adèle wrote3, “had attracted to M. Victor Hugo numerous demands from composers, among others from the illustrious M. Meyerbeer, who desired him to make an opera of his romance. He had always refused them. But M. Bertin asked him to do it for his daughter, and he did out of friendship that which he had not done out of interest.”

Bertin seems to have been a talented amateur musician. Hector Berlioz4 (Mémoires) admired her as “one of the strongest female intellects” of his day. Elsewhere, reviewing the opera in the Journal des Débats5, her family paper, he wrote: “Mlle Bertin has read a lot, written a lot, and reflected even more in order to acquire complete knowledge of everything related to the theory of her art. Thus, she has made great progress on the thorny path leading to strong and lasting compositions. Highly skilled in harmonic combinations, even the most difficult ones, endowed with a true sense of expression and dramatic propriety, naturally inclined towards purity and elevation in melodic style, she has also gained, through the contemplation of the works of certain masters, what a long practice barely provides to others: skill and ease in handling masses, in the conduct of long pieces, and in the use of instrumentation. The fear of being accused of weakness in this last regard may have sometimes led her to fall into the exaggeration of strength.”

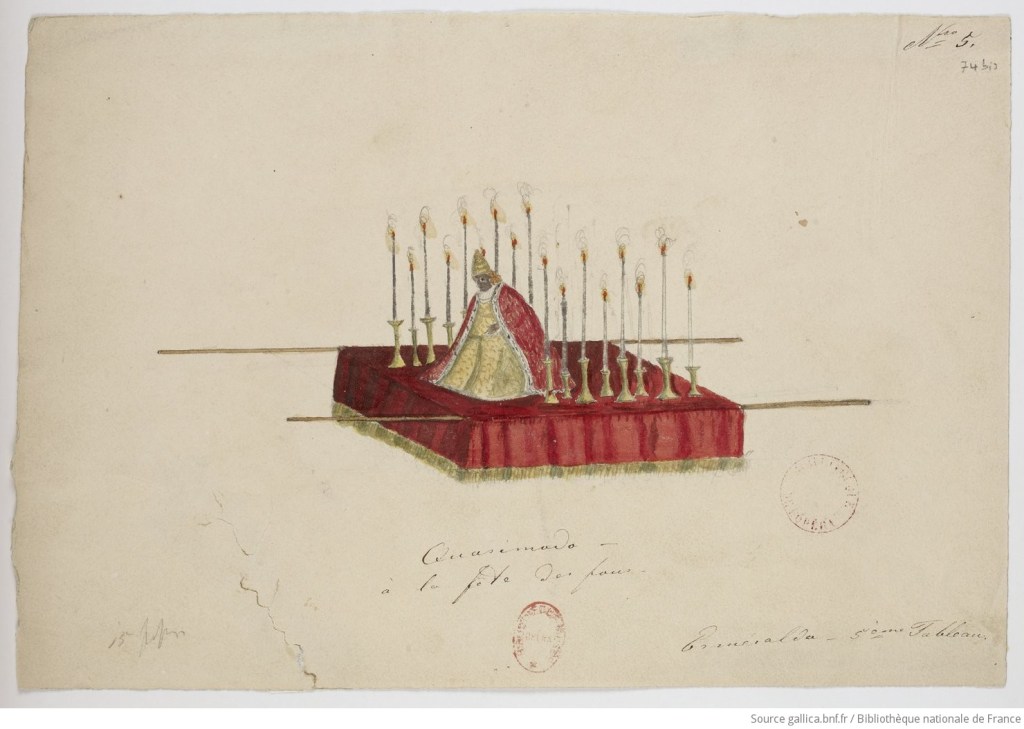

Through her family connections, her opera, her fourth, was staged; and because of them, it failed. Her music, however, is not at fault. It is splendidly tuneful; like the gypsy Esmeralda, it dances. “It was indefinable and charming; something pure, resonant, airy, almost winged. There were constant blossoms, melodies, unexpected cadences…”6 Bertin handles the grand opéra standards – crowd scenes, processions, drinking songs, choruses of priests or watchmen – splendidly; the music moves from melody to melody swiftly; and her instrumentation is often ingenious. At its best, as in the Act III trio or the magnificent final scene (Esmeralda at the scaffold, comprising an allegro chorus, a mass for the dead, and a trio rising to an ecstatic climax), it soars. A list of highlights would be boring, and would comprise most of the pieces in the opera. What first come to mind are the procession du pape and the watchmen’s chorus in Act I; in the first scene of Act II, Quasimodo in the pillory, with a Rossinian patter chorus and ensemble; and in the second scene, the arrival of the guests and the finale in ¾ time; the chanson at the start of Act III; and the most ‘famous’ piece in the opera, Quasimodo’s air des cloches. Overall, the ensembles and choruses make more impression than the solo arias, whose melody can be hard to grasp. There is, however, the occasional trivial or overly Italianate gesture, and what sound like quotes from Les Huguenots (the duet in Act I) or Auber’s Gustave III (Act II). The only recording (2008 Forster) is abridged, however; many of the orchestral passages and some of the choruses or repeats are cut.

“This work by a woman who had never penned a line of criticism on anything, who had never attacked or spoken ill of anyone, and whose only fault was being part of the family of directors of a powerful newspaper, the political leanings of which a certain public detested at the time, this work, much superior to many productions that we see succeed or at least be accepted daily, fell with a deafening crash,” Berlioz7 recalled in his Mémoires.

Berlioz saw it unfold at first-hand; the Bertins had commissioned him to supervise rehearsals for the opera, as the wheelchair-bound Mlle Bertin was “unable to personally oversee or direct the rehearsals of her score at the theatre”. The leading rôles, Berlioz remarked, were performed by the best singers and actors at the Opéra at that time: the tenor Adolphe Nourrit as Phœbus, the bass Nicolas Levasseur as Frollo, the soprano Cornélie Falcon as Esmeralda, and the tenor Massol as Quasimodo. But, Cairns8 writes in his biography of Berlioz: “It was disillusioning even beyond what he already knew of the Opéra to witness the casualness and want of zeal.” The singers were unenthusiastic; so were the musicians; and rumours flew around that Berlioz had written the music. (On the first performance, Alexandre Dumas yelled that Berlioz had composed the air des cloches – which that musician stoutly denied.)

Some of the criticism was aimed at Mlle Bertin’s style. It was, L’Indépendant9 observed, severe, Germanic in form, and very elaborate, but sometimes lacked inspiration, while the composer was not accustomed to writing for voices.

Other critics were harsher. “A beautiful duet, a charming romance sung by Mlle Falcon, the distinctive air of the bells, and the finale of the fourth act are the only elements that recommend the work to the applause of the crowd,” Le Ménestrel10 summed up. “Otherwise, there is little melody, a lot of brass, and a tiresome monotony. Let’s admit that the poet has a rôle in the magnificent boredom that hovers over this vast conception. M. Victor Hugo took his novel, the most admirable of his novels, and without pity for his sublime creation, amused himself by mutilating, dismembering, shredding, dismantling, and mincing it into pieces to suit the tastes of the Rue Lepelletier. No more cohesion, no more interest! Nothing! Except for a few energetic verses that Mlle Bertin drowned out with the clamour of her instruments.”

Le Journal des Beaux-arts11 expressed a similar view: “M. Hugo, by cutting himself up, has turned a good novel into a poor opera. He took some scenes from the novel without bothering to co-ordinate or link them, to create a dramatic action, and to infuse interest into the drama. Consequently, if you had the misfortune not to know or to have forgotten his novel, your understanding of the drama would be constantly lacking… As for Mlle Bertin, she gave the orchestra a lot of work, which, despite its intelligence, unfortunately did not always understand her. Besides, in the score, the instrumentation is often troubled, tangled, full of noisy tutti; the melodies are almost always pale and sometimes bizarre.”

Even Berlioz12 himself (Revue et gazette musicale de Paris) thought that Mlle Bertin’s orchestration was “generally too heavy, too harsh for the voices”; and there were too many trumpets, trombones, and ophicleides. But the score was “quite remarkable in many respects, with faults that experience can eliminate and beauties that generally reveal in the author a rare sense of style and strongmindedness”.

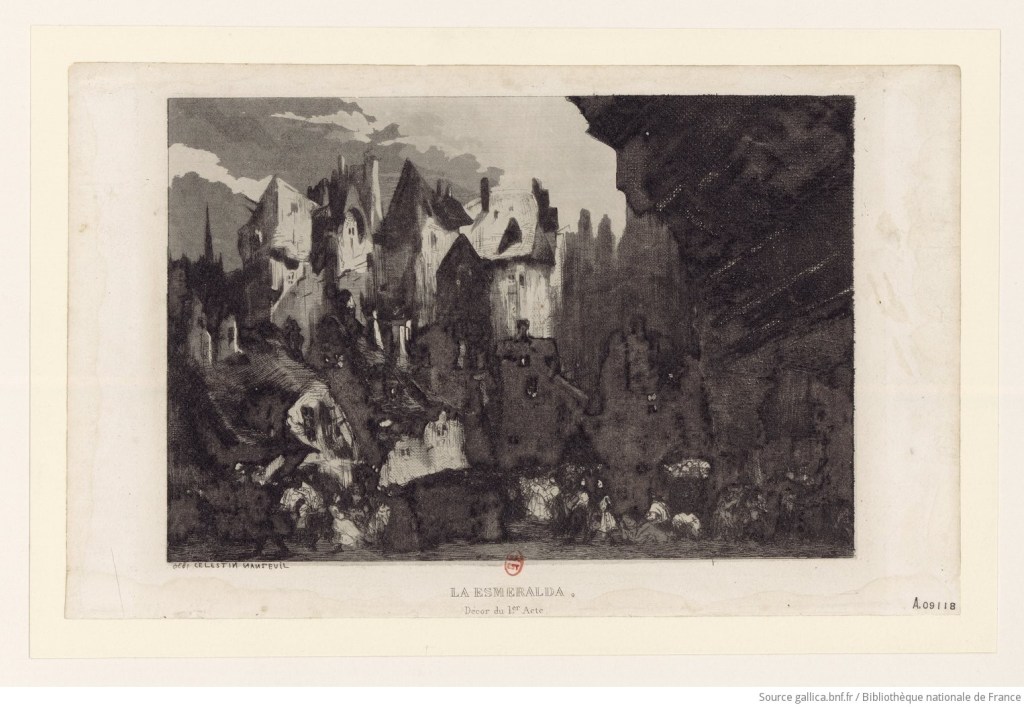

Victor Hugo himself had some complaints about the production, his wife13 remembered. “He was struck by the meanness of the scenic representation. Old Paris gave way to decorations and costumes. Nothing rich nor picturesque; the tatters of the Cour des Miracles, which might have been characteristic and a novelty at the Opéra, were of new cloth; so that the lords had the appearance of poor people and the vagrants of bourgeois. M. Victor Hugo had given an idea of a mechanical effect which would have been very successful: the ascension of Quasimodo carrying Esmeralda from storey to storey; to allow Quasimodo to rise it was only necessary to lower the cathedral. In his absence the thing had been declared impossible. This mechanical effect, impossible at the Opéra, was afterwards produced at L’Ambigu.”

What really killed the opera, however, was a campaign mounted against it – or against the Bertin family and the Journal des Débats. “The journals exhibited extreme violence against the music,” Adèle Hugo14 wrote. “Party spirit mingled in this, and avenged itself upon the journal of the father through the daughter.”

“Some individuals who do not share the opinions of that newspaper,” wrote L’Indépendant15, “were determined to forcefully revive, in connection with the performance of this young lady’s work, those ridiculous conflicts that marked the final years of the Restoration, when liberals mercilessly booed, whether it was good or bad, any production that did not belong to a writer of their political persuasion. Two or three newspapers had even positioned themselves as the mouthpiece of this brutal opposition, whose hatred extended even to works of art.

“Although the offices were not open last Monday, this Machiavellian tactic began. Some hecklers infiltrated the friendly ranks of the crowd, and these gentlemen put on a bold front. However, they could not boast say, with the great satirist Boileau, ‘It’s a right one buys at the door upon entering’. For no tickets had been legally sold, and these troublemakers could only obtain them in the vicinity of the theatre, where, it is said, there is a scandalous trade taking place every night that the management is reportedly working to suppress.”

The hit of the evening was Quasimodo’s bell aria. “As it could neither be annihilated nor contested in its effect,” Berlioz16 (Mémoires) wrote, “some audience members who were particularly fervent against the Bertin family shamelessly exclaimed, ‘It’s not hers! It’s not Mlle Bertin’s! It’s by Berlioz!’, and the rumour that I had written this piece of music imitating the Esmeralda score was actively spread by these people. However, as with the rest of the score, I was completely uninvolved with this piece of music, and I swear upon my honour that I did not write a single note of it. Yet, the cabal was too determined to unleash their fury against the author not to make the most of the pretext offered by my involvement in the studies and staging of the work; the air of the bells was decidedly attributed to me.”

At the time, Berlioz likewise told the readers of the Revue et gazette musicale17 that he considered the aria a little masterpiece: “The modulations, the linking of phrases, the melodies, the rhythm, the progression of effects – everything is chosen with astonishing artistry. It is tastefully picturesque, captivates the imagination, and seizes it completely from the first measures.” In a footnote, Berlioz noted that, although he was credited with the composition or at least orchestration of the piece, “such an honour, which he would consider himself fortunate to deserve, he wholeheartedly returns to Mlle Bertin, while protesting in the most formal manner that she alone conceived, wrote, and orchestrated this beautiful aria, as with everything else”.

“Hisses, shouts, and jeers, unprecedented until then, greeted [Esmeralda] at the Opéra,” Berlioz18 continued in his Mémoires. On a later performance19, during the last act, the groundlings rioted. “Down with the Bertins! Down with the Journal des Débats! Bring down the curtain!” they shouted.20 And the curtain fell.

La Esmeralda was performed six times by the end of 1836, five in 1837, and six in 1838; thenceforward, Act I alone was performed as a curtain-raiser (three times in 1838 and five in 1839). Barring a piano-accompanied performance for Hugo’s bicentenary in 2002, It was not revived until 2008.

Mme Hugo21 implies that the work was cursed. “The romance is founded upon the word Ἀνάγκη, the opera ends by the word fatalité. A first fatality was this suppression of a work the singers of which were M. Nourrit and Mademoiselle Falcon, the composer a woman of great talent, the librettist M. Victor Hugo, and the subject Notre-Dame de Paris. The fatality followed the actors. Mademoiselle Falcon lost her voice; M. Nourrit soon after committed suicide in Italy. A ship called Esmeralda, crossing from England to Ireland, was lost, vessel and cargo. The Duke of Orléans named a mare of great value Esmeralda; in a steeple-chase she ran against a horse at a gallop and got her head broken.”

Berlioz’s22 judgement, however, remained positive. “[Mlle Bertin’s] musical talent, in my opinion, is more rational than emotional, but it is real nonetheless,” he wrote in his Mémoires. “Despite a certain indecision that is generally noticed in the style of her opera Esmeralda and the occasionally childlike forms of her melody, this work … certainly contains some very beautiful and highly interesting parts.”

This is an opera that could interest and please audiences today. It is based on a famous and still popular novel, and, while the story veers dramatically from its original, that has not prevented the success of various film or Disney adaptations. Besides, it is a rare opera by a woman composer, and one, moreover, that is consistently tuneful and entertaining.

Costume sketches

Recording

Listen to: Listen to: Maya Boog (Esmeralda) Manuel Nuñez Camelino (Phœbus), Francesco Ellero d’Artegna (Frollo), Frédéric Antoun (Quasimodo), and Yves Saelens (Clopin), with the Orchestre National de Montpellier Languedoc-Rousillon, conducted by Lawrence Foster, 2008.

Works consulted

- L’Indépendant, 18th November 1836

- Le Ménestrel, 20th November 1836

- Hector Berlioz, Revue et gazette musicale, 20 November 1836

- Journal des Beaux-arts, 20th November 1836

- Hector Berlioz, Journal des Débats, 15 July 1838

- Hector Berlioz, Mémoires, 1870

- Adèle Hugo, Victor Hugo by a witness of his life, trans. Charles Edwin Wilbour, New York: Carleton, 1863.

- David Cairns, Berlioz, vol. II: Servitude and Greatness 1832–1869, Allen Lane / the Penguin Press, 1999.

- Levi Nigel Xenon Walls, “Composing-out Notre-Dame: How Louise Bertin Expresses the Hugolian Themes of Fate and Decay in La Esmeralda”, University of North Texas, 2018

- Phil’s Opera World

- Casimir Delavigne, Revue des Deux Mondes, no. 1, 1831. ↩︎

- L’Indépendant, 18 November 1836. ↩︎

- Adèle Hugo, Victor Hugo by a witness of his life, trans. Charles Edwin Wilbour, New York: Carleton, 1863, p. 169. ↩︎

- Hector Berlioz, Mémoires, Ch. 48. ↩︎

- Hector Berlioz, Journal des Débats, 15 July 1838. ↩︎

- Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, livre II, chapitre 3. ↩︎

- Hector Berlioz, Mémoires, op. cit. ↩︎

- David Cairns, Berlioz, vol. II: Servitude and Greatness 1832–1869, Allen Lane / the Penguin Press, 1999, p. 121. ↩︎

- L’Indépendant, 18 November 1836. ↩︎

- Le Ménestrel, 20 November 1836. ↩︎

- Journal des Beaux-arts, 20 November 1836. ↩︎

- Hector Berlioz, Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, 20 November 1836. ↩︎

- Adèle Hugo, op. cit., p. 170. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- L’Indépendant, op. cit. ↩︎

- Berlioz, Mémoires, op. cit. ↩︎

- Berlioz, Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, op. cit. ↩︎

- Berlioz, Mémoires, op. cit. ↩︎

- The second, according to Berlioz (Mémoires); the fifth, according to Cairns; the eighth, according to Adèle Hugo. ↩︎

- Cairns, op. cit., p. 123. ↩︎

- Adèle Hugo, op. cit., p. 170. ↩︎

- Berlioz, Mémoires, op. cit. ↩︎

I like this opera and often listen to it just because the music itself is so good. It is flat dramatically, and certainly doesn’t pack the punch that the novel does.

LikeLike

You can blame Hugo for that; his approach to adapting his own material was rather odd!

Bru Zane has recorded another Bertin opera, Fausto (in Italian).

LikeLike