Rienzi, der letze der Tribunen

- Opera in 3 acts

- Composer: Richard Wagner

- Libretto: Wagner, based on Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel Rienzi, the last of the tribunes (1835)

- First performed: Königliches Hoftheater Dresden, Germany, 20th October 1842

Characters

| COLA RIENZI, Papal notary | Tenor | Josef Tichatschek |

| IRENE, his sister | Soprano | Henriette Wüst |

| STEFANO COLONNA, a Roman patrician | Bass | Georg Wilhelm Dettmer |

| ADRIANO, his son | Mezzo | Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient |

| PAOLO ORSINI, a Roman patrician | Bass | Johann Michael Wächter |

| RAIMONDO, a Papal legate | Bass | Gioacchino Vestri |

| BARONCELLI and CECCO DEL VECCHIO, Roman citizens | Tenor Bass | Friedrich Traugott Reinhold Karl Risse |

| A Messenger of Peace | Soprano | Anna Thiele |

| A Herald | Tenor | |

| Ambasadors from Lombardy, Naples, Bavaria, Bohemia, etc. Roman Nobles, Citizens, People, Messengers of Peace, Priests and Monks of all Orders, Roman Soldiers, Guards, Characters in Pantomime |

SETTING: Rome, towards the middle of the 14th century.

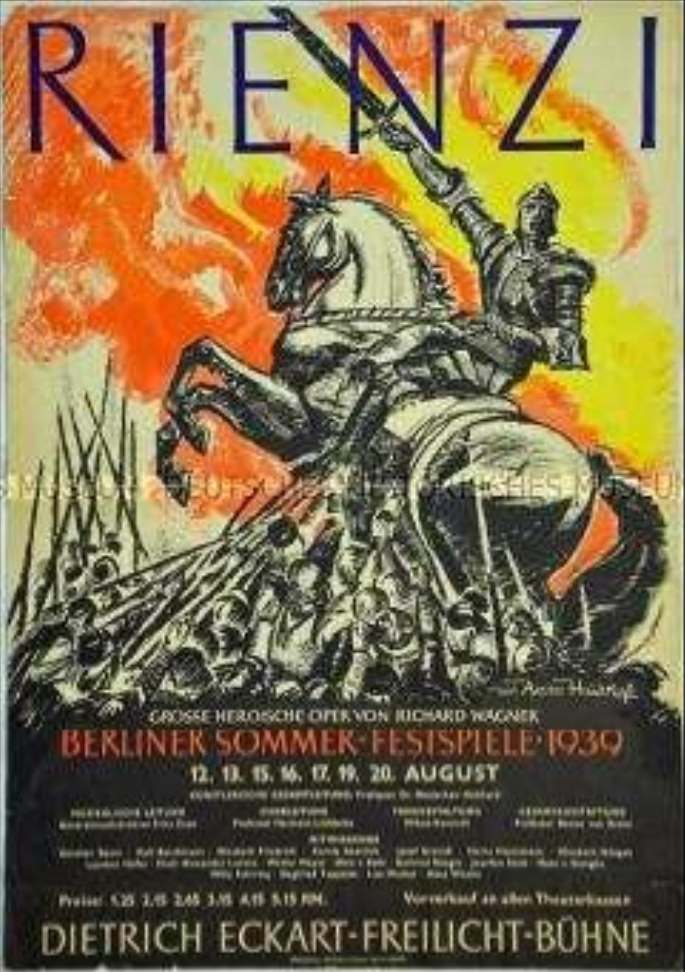

Rienzi was Hitler’s favourite opera – and of all Wagner’s works, it is the one most contaminated by association with the Führer. The idea for National Socialism came to the teenage Hitler at a 1906 performance. “In jener Stunde begann es,” Hitler declared: “In that hour, it began.”

Hitler was enthralled by the heroic depiction of a charismatic demagogue, the mystic embodiment of the will of the people.

“At the age of 24, this man, an innkeeper’s son, persuaded the Roman people to drive out the corrupt Senate by reminding them of the magnificent past of the Roman Empire,” the dictator recalled. “Listening to this blessed music as a young man in the theatre at Linz, I had the vision that I too must someday succeed in uniting the German Empire and making it great once more.”

Even Rienzi’s fate in this opera – dying, rejected by his people, amidst the burning Capitol – prefigured Hitler’s demise. (Hitler thought Rienzi’s mistake was that he did not have the SS to protect him.) When Hitler committed suicide in the Berlin bunker, the manuscript score (presented to her beloved ‘Wolf’ by Winifred Wagner) went up in flames with him.

I am loth to agree with Hitler; he wasn’t always right. In fact, given he was wrong about a few things, some of them rather fundamental, should we trust him (of all people) on this? As Alex Ross comments: “The danger inherent in the incessant linking of Wagner to Hitler is that it hands the Führer a belated cultural victory – exclusive possession of the composer he loved.” One could suggest that Hitler’s interpretation of Rienzi need not have been Wagner’s; the young composer was a left-wing revolutionary, and at the time, influenced by the progressive utopian doctrine of Saint-Simonianism1. Verdi, after all, considered composing an opera of Cola di Rienzo, seen as a hero of the Risorgimento – but then Mussolini modelled himself on Rienzi. Dictators are inextricable from Rienzi.

Unfortunately, this is indeed a fascist opera, indeed a proto-Nazi one. Its aesthetic is totalitarian: excessive visual display, communal expressions of nationalistic fervour, the worship of force, military processions, marches, heroic oaths, and a score that sounds like the Horst Wessel Lied.

It was also Wagner’s first successful opera, and, worryingly, one of his most popular operas in Germany.

After the failure of Die Feen and Das Liebesverbot, Wagner wanted to write a crowd-pleasing blockbuster. “The ‘grand opera’, with all its scenic and music display, its sensationalism and massive vehemence, loomed large before me; and not merely to copy it, but with reckless extravagance to outbid it in every detail, became the object of my artistic ambition.”2 It was inspired by the heroic operas of Spontini (especially Fernand Cortez) and the works of Auber, Meyerbeer, and Halévy. (Later, ashamed of these influences, Wager dismissed Rienzi as unimportant; it did not mark any essential phase in the development of his views on art.) It would be an enormous work “for whose production only the most exceptional means should suffice”. Perhaps Paris or Berlin would stage it; it would be impossible, Wagner3 hoped, for any lesser theatre to stage it. But Pillet, director of the Paris Opéra, to whom Wagner offered it, wanted no bar of it; the Théâtre de la Renaissance, that did, went bankrupt before rehearsals could begin. At last, thanks to Meyerbeer’s influence, it was staged in Dresden in 1842.

Rienzi impressed German-speaking audiences. Eduard Hanslick (later pilloried as Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger) considered it “the finest thing achieved in opera in the last 12 years, the most significant dramatic creation since Les Huguenots, and just as epoch-making for its own time as were Les Huguenots, Der Freischütz, and Don Giovanni, each for its respective period of musical history”. Meyerbeer himself had called it “rich in fantasy and of great dramatic effect”. It was performed 200 times in Dresden by 1908, and produced throughout Europe and America.

The French rightly hated it. It was staged by the Théâtre-Lyrique in April 1869, with an unprecedented luxury of sets and costumes – and lasted barely 20 performances. “The audience didn’t even bother getting angry at the mediocre music, which followed the accepted methods of all schools,” remarked Albert de Lassalle.4 “Despite the noise, it wasn’t Wagnerian enough to induce nausea. No-one was fooled into mistaking for high art what was nothing more than coarse art.” The venture, Félix Clément5 commented, proved more ruinous than profitable for Pasdeloup’s management; he was criticised for spending considerable sums on a piece that teenagers would find disjointed and absurd, with deafening music. Wagner had not been forgiven for the fiasco of Tannhäuser eight years before. Clément6 thought Rienzi, exhausting and “emptily and relentlessly noisy”, should be called Much Ado About Nothing. “A warlike tumult prevails throughout this piece. I don’t believe there is a single opera where tutti passages are so frequent, and brass instruments play such a predominant rôle. It’s a clamour and a jumble.”

Indeed, Wagner’s idea of “outbidding” grand opera is to flatten the listener into submission for nearly five hours. (Four hours and 40 minutes, to be precise. The first performance, including intervals, lasted seven hours.) Rienzi is an elephantine, enormously bombastic monstrosity. The music is overwhelmingly forceful and strident; the director David Pountney7 described it as “unashamed, bullying, hectoring hysteria”. Because it is pitched at a constant level of high excitement, it seems overheated, then exhausting, then deeply boring. It’s monotonous. Processions, marches, oaths, battles, and crowd scenes galore. The BRASS! Trumpets! Brass! Drums! Brass! (Wagner certainly had some.)

Nevertheless, the opera itself feels small scale. There’s little in the way of action, and certainly not enough to justify this gargantuan expenditure of musical and scenic resources. In other words: effects without causes!

Briefly: Since the pope left Rome for Avignon, the eternal city has declined; the people are oppressed by warring factions of patricians, noble but ignoble. Rienzi, tribune of the people, ends their quarrel, is hailed as tribune of the people, and declares the liberty of the masses (Act I). Rienzi watches a ballet, and escapes an assassination attempt, thanks to his dagger-proof armour (Act II). Rienzi defeats the patricians’ army; his sister’s boyfriend’s father is killed (Act III). Rienzi is excommunicated (Act IV). The people turn on Rienzi; the tribune, his sister, and her boyfriend, are killed when the burning Capitol collapses on them.

The characters lack interiority. Throughout the opera, political identity triumphs over private feeling. Rienzi is entirely a political animal, given to grandstanding, rabble-rousing, and declamatory rhetoric. Nearly all his lines are propaganda, spoken with an eye to their effect on his audience. He has a sense of purpose and complete conviction, but no inner life; the only time he is alone on stage is his prayer at the start of Act V, and even that is a plea to continue his mission. His greatest love is Rome (“Roma heißt meine Braut!”).

His sister Irene (a fundamentally passive character) is given the choice between being a woman or a Roman (“Kein Rom gibt’s mehr, sei den ein Weib!”). Impossible to be both, according to Wagner. She unhesitatingly chooses her brother / Rome over her lover Adriano.

Adriano is the only character who is motivated by private feelings, torn between his love for Irene, his admiration and then hatred for Rienzi, and his duty to his father Colonna. Rienzi’s decision to spare the noblemen (Act II), at the pleading of Adriano and Irene, is privately motivated and politically disastrous.

True, there are moments of genuine beauty and effectiveness. The majestic overture – which opened Nazi party rallies in Nuremberg, natch – features the broad, noble theme of Rienzi’s Prayer, the hymn Santo spirito cavaliere, and energetic passages from the act finales; it ends with a series of exciting crescendos.

The Act I introduction has an impressive ensemble, as Rienzi quells a brawl, while the finale has tremendous oath-swearing scene, “Wir schwören dir so gross und frei soll Roma sien, wie Roma war”; overall, that finale is grand and inspiring. Nevertheless, the words are dubious:

RIENZI:

Der Staat verbleibe seinem Haupt.

Gesetze gebe ein Senat.

Doch wählet ihr zum Schützer mich

der Rechte, die dem Volke zuerkannt,

so blickt auf eure Ahnen

und nennt mich euren Volkstribun.

VOLK:

Rienzi, Heil dir, Volkstribun!

Dir huldigt freier Römer Schwur!

Wir schwören dir, so groß und frei

soll Roma sein, wie Roma war.

Vor Niedringkeit und Tyrannei

sie unser letztes Blut bewahr’!

Schmach und Verderben schwören wir

dem Frevler an der Römer Her’!

Ein neues Volk erstehe dir,

wie seine Ahnen groß und hehr!

(RIENZI: Let the state remain without a head, let a Senate make the laws. Yet you have chosen me your protector, the right man, recognised by the people, so look back to your ancestors, and call me your Tribune of the People.

PEOPLE: Heil Rienzi, Tribune of the People! The oath of free Romans is your homage. We swear to you, Rome shall be as great and free as Rome once was. May the last drop of our blood protect us from subjugation and tyranny! Death and destruction we pledge to the blasphemer, and honour to the Roman! A new people shall arise before you, as great and magnificent as its ancestors!)

Act II – which goes for more than an hour and a half – is both dull and bombastic. The chorus of the Messengers of Peace is quite pretty, but outstays its welcome. After that scene, commented Le Ménestrel8, the spectator’s pleasure is over. Much of the act is occupied by a gargantuan ballet. O God, the ballet. Do you think of ballet as graceful and elegant? Or do you think of it as 40 minutes of ffff that makes the walls of the house shake and your eardrums bleed? What sort of dancers was Wagner imagining? They certainly weren’t human. The adagio section of the finale, “O last der Gnade Himmelslicht”, however, is beautiful.

Act III is the nadir of the opera, and appalling from start to finish. Here the fascism reaches its apogee, amidst eight-and-a-half minute marches, belligerent speeches, and war hymns.

RIENZI:

Der Tag ist ja, die Stunde naht

zur Sühne tausendjähr’ger Schmach!

Er schaue der Barbaren Fall

und freier Römer hohen Sieg!

So stimmt denn an den Schlachtgesang,

er soll der Feinde Schrecken sein!

Santo Spirito cavaliere!

SCHLACHTHYMNE:

Auf, Römer, auf, für Herd’ und für Altäre!

Fluch dem Verräter an der Römer Ehre!

Nie sei auf Erden ihm die Schmach verziehn,

Tod seiner Seel’, es lebt kein Gott für ihn!

Trompeten schmettert, Trommeln wirbeit drein,

es soll der Sieg der Römer Anteil sein!

Ihr Rosse stampfet, Schwerter klirret laut,

heut ist der Tag, der eure Siege schaut!

Paniere weht, blinkt hell, ihr Speere!

(RIENZI: The day has dawned, the hour is approaching to expiate a thousand years of shame! May it see the downfall of the barbarians and the great victory of free Romans! So all join in the battle hymn, that it may strike fear into the enemy’s heart! Santo Spirito cavaliere!

BATTLE HYMN: Arise, Romans, arise, for your homes and your altars! Cursed be he that betrayed the honour of Rome! May the shame never be forgiven him on earth, death to his soul, there is no God living for him! Let the trumpets sound and the drums roll to take part in the Roman’s victory! Horses stamp, swords loudly clatter, this is the day which will see your victory! Standards wave, brightly glint, spears!)

It is music to goosestep to.

“The third act is bad,” declared Le Ménestrel. “I could, out of an excess of conscientiousness, point out certain phrases here and there, but they are drowned, submerged in the almost continuous uproar of a circus-like music: nothing but marches, fanfares, drum rolls, war songs on foot and on horseback, departure and return songs, victory choruses, several of which seemed to me to push the boundaries of triviality. The poverty of the motifs is only imperfectly concealed by the dense harmonies that almost everywhere underlie them, and by the orgiastic abuse of vocal and instrumental sonorities.”

The only other notable part of the score is Rienzi’s beautiful prayer (Act V), “Allmächt’ger Vater, blick herab!”. Praised by Berlioz, it is a well-known tenor recital piece.

To call Rienzi, this heavy, bloated, bloviated, monstrous, metallic thing, “Meyerbeer’s best opera” (Hans von Bülow, famously cuckolded by Wagner) is an insult to that composer. Rienzi glorifies strength, power, force, and fanaticism – everything the cosmopolitan, liberal Meyerbeer detested. (William Pencak9, in fact, suggests that Le Prophète was intended as a “riposte” to Rienzi and a critique of its fiercely militant nationalism.) True, Wagner surely had the Huguenots Act III finale in mind when he wrote the big choruses in Acts I & V, just as the Adriano/Irene love duet in Act III is modelled on the Raoul/Valentine duet, and Rienzi’s death scene is an imitation of the massacre of the Huguenots. But it’s hard to imagine anything less Meyerbeerian than this score. Meyerbeer’s operas are well paced, ironic, full of inventive and often delicate instrumental colour, subtlety, charm and warmth; Rienzi is not.

As Thomas Grey10 and Paul Lawrence Rose11 suggest, Hitler acted on what was in the text: “resentful hatred” and “messianic political revolutionism”, “mass politics, propaganda, the Führer-principle”. (It would be fascinating to stage it with Coriolanus as a study in demagoguery.) The fact remains that there’s something deeply and unattractively proto-Fascist about Rienzi. Or, as Wagner himself later came to think of it: “Repugnant.”

See also Phil’s Opera World.

Recordings

Listen to: John Mitchinson, Lorna Haywood, Michael Langdon, and Raimund Herinckx, with the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Edward Downes, BBC, 1976. (Complete and uncut recording of Wagner’s “original” 1842 version.

René Kollo, Siv Wennberg, Janis Martin, Theo Adam, Peter Schreier, and Nikolaus Hillebrand, with the Staatskapelle Dresden, conducted by Heinrich Hollreiser, EMI, 1976. Complete recording of Wagner’s shortened 1843 version. (Slightly more palatable.)

- Laura Stanfield Pritchard, “Wagner and the Grand Operatic Tradition”, Odyssey Opera, 2013. ↩︎

- Richard Wagner, A Communication to My Friends (1851). ↩︎

- Richard Wagner, “Autobiographical Sketch”, pp. 246–47 ; My Life, p. 185. ↩︎

- Albert de Lassalle, Mémorial de Théâtre-Lyrique (1877) : « Cependant Rienzi disparut après une vingtaine de représentations pénibles. Le public n’eut pas même de colère contre une musique médiocre mais conçue d’après les procédés acceptés par toutes les écoles, et qui, malgré son vacarme, n’était pas assez wagnérienne pour provoquer des haut-le-cœur. Personne ne s’y trompa et ne voulut prendre pour du grand art ce qui n’était que du gros art. » ↩︎

- Félix Clément, Dictionnaire des opéras (1872) : « M. Pasdeloup a beaucoup fait pour installer chez nous M. Wagner ; en faisant exécuter pendant plusieurs années, par son orchestre dans les Concerts populaires, les quatre meilleurs morceaux de son compositeur favori, il est parvenu à lui donner une grande notoriété ; il lui a recruté des partisans ; mais on peut affirmer qu’il n’a pas été récompensé de ses labeurs. Il a monté l’opéra de Rienzi avec un luxe de décors et de costumes qu’on n’avait jamais vu au Théâtre-Lyrique, et cette entreprise a été plutôt ruineuse que profitable à sa direction et à l’art ; on l’a blâmé d’avoir fait des frais aussi considérables pour une pièce telle que beaucoup de collégiens de treize à quatorze ans n’en imagineraient pas une plus décousue et plus absurde, et pour une partition dont la musique a été jugée assourdissante. » ↩︎

- Clément, op. cit.: « Tout le reste est d’une sonorité creuse et impitoyable. La fréquence des tutti, les tremolo et l’emploi constant des instruments de cuivre rendent l’audition de cet opéra très fatigante, et son véritable titre devrait être : Much ado about nothing… Le chœur des messagers de la paix et les couplets de soprano qui y sont intercalés se détachent gracieusement sur ce fond lourd et chargé de sonorités excessives. De même, la prière de Rienzi, à la fin de l’ouvrage, a paru délicieuse à entendre, en raison du contraste qu’elle forme avec le tumulte belliqueux qui règne dans l’ensemble de l’œuvre. Je ne crois pas qu’il existe un seul opéra où les tutti soient si fréquents et où les cuivres jouent un rôle aussi prépondérant. C’est du fracas et du fatras. » ↩︎

- David Pountney, “Directing grand opera: Rienzi and Guillaume Tell at the Vienna State Opera”, in David Charlton (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Grand Opera, Cambridge University Press, 2003. ↩︎

- Gustave Bertrand, Le Ménestrel, 11 April 1869. ↩︎

- William Pencak, “Why we must listen to Meyerbeer” (1999), in Robert Ignatius Letellier (ed.), Giacomo Meyerbeer: A Reader, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007. ↩︎

- Thomas Grey, “Richard Wagner and the legacy of French grand opera”, in David Charlton (ed.), Cambridge Companion to Grand Opera, 2003, pp. 327-28. ↩︎

- Paul Lawrence Rose, Wagner: Race & Revolution, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1992, pp. 25-26. ↩︎

7 thoughts on “279. Rienzi (Wagner)”