Tannhäuser und der Sängerkrieg auf Wartburg

- Romantische Oper in 3 acts

- Composer / libretto: Richard Wagner

- First performed: Königlches Hoftheater, Dresden, Germany, 19th October 1845

Characters

| HERMANN, Landgrave of Thuringia | Bass | Georg Wilhelm Dettmer |

| Knights and singers: | ||

| TANNHÄUSER | Tenor | Josef Tichatschek |

| WOLFRAM VON ESCHENBACH | Baritone | Anton Mitterwurzer |

| WALTHER VON DER VOGELWEIDE | Tenor | Max Schloss |

| BITEROLF | Bass | Johann Michael Wächter |

| HEINRICH DER SCHREIBER | Tenor | Anton Curty |

| REINMAR VON ZWETER | Bass | Karl Risse |

| ELISABETH, the Landgraf’s niece | Soprano | Johanna Wagner |

| VENUS | Soprano | Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient |

| A Young Shepherd | Soprano | Anna Thiele |

| Four Squires | Sopranos and Altos | |

| Thuringian knights, counts and noblemen, noblewomen, older and younger pilgrims | ||

Setting: The interior of the Höselberg near Eisenach; the Wartburg.

Time: At the beginning of the 13th century.

For a quarter of a century, Richard Wagner had dreamt of having his works performed in Paris, but when Tannhäuser was finally staged there in 1861, sixteen years after its German première, everything went wrong.

The Jockey Club, a horde of wealthy philistines, rioted, booing and hooting on whistles, so the music could scarcely be heard. Many in the audience were bored, and the critics complained that the opera was undramatic and antimusical. After three performances, Wagner pulled his work, and returned to Germany; none of his operas would be staged in Paris until the end of the century. It “must be the bitterest and cruellest disappointment that Richard Wagner has ever experienced in his artistic life”, La Causerie1 wrote sympathetically.

Lohengrin would have been a better choice for Paris, no doubt, but at this remove, the hostility to Tannhäuser is rather baffling. It is recognisably grand opéra, not yet music drama, and it has some of Wagner’s best melodies.

Synopsis

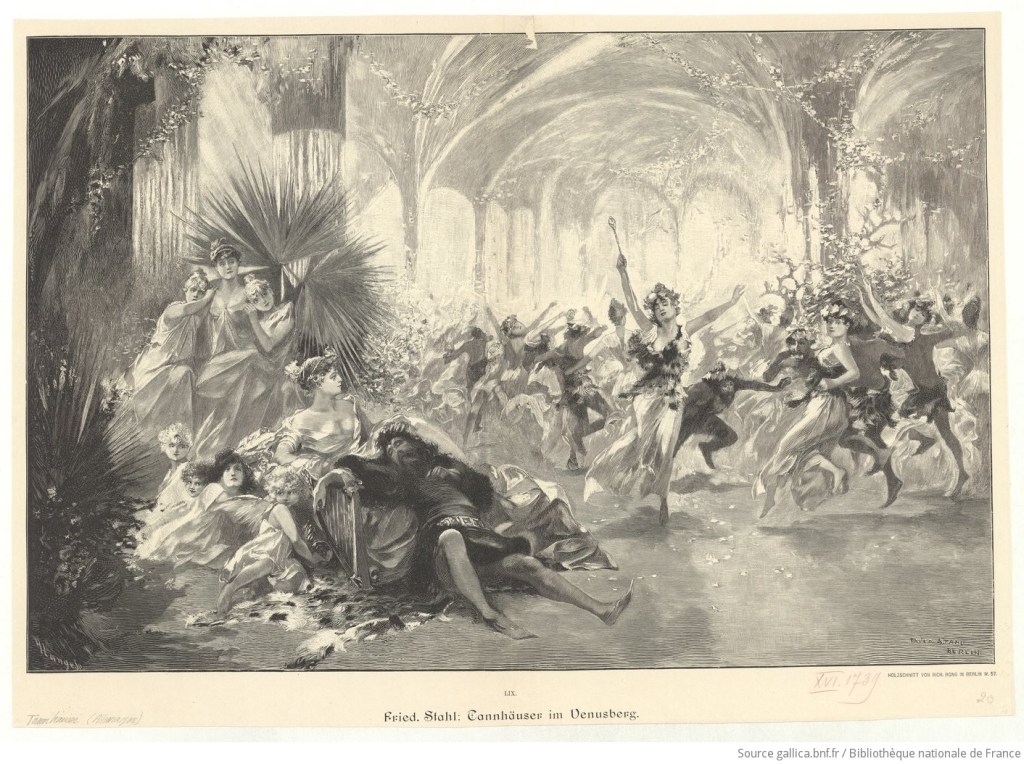

Its story unites two German legends: the Venusberg, where the goddess of carnal love (or the Norse fertility goddess Holda) was supposed to reside when Christianity chased the Classical deities away; and the Singers’ Tournament at the Wartburg Castle. Like The Flying Dutchman, a sinful man is redeemed by the love of a good woman. But its chief operatic forebear is clearly Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable (1831): the tenor vacillates between two opposing forces, one ‘evil’ and one ‘good’ (the agent of the Madonna); competes at a tournament for the favour of a princess; and is saved from damnation at the end by an act of grace. Some of the iconography recalls Meyerbeer’s opera, too: the heroine kneels at a shrine and prays, and the ballet of fornicating nymphs and satyrs was as provocative in its time as Robert’s undead nuns.

Tannhäuser, a Minnesinger (a minstrel-knight and writer of poems of courtly love), has quarreled with the other Minnesingers and spent a year with Venus, in her grotto in the Venusberg. He frees himself from her spell by invoking the Virgin Mary, and returns to the world of men. The minnesingers persuade him to return to the court of the Landgrave of Thuringia. There, a tournament of poetry is held, at which Elisabeth, the Landgraf’s niece and Tannhäuser’s lover, presides. Tannhäuser, irritated by the other minnesingers’ bland songs, sings a song in praise of Venus. All recoil as they realise that he has been to the Venusberg. The Landgraf and knights condemn Tannhäuser to death, but Elisabeth begs for mercy; surely, she asks, a sinner should seek atonement? The Landgrave exiles Tannhäuser and orders him to go on pilgrimage to Rome. When the pilgrims return, however, Tannhäuser is not among them. He appears at last, and tells his friend Wolfram von Eschenbach that, although he mortified his flesh and sought to atone his sins, the Pope would not forgive him. Only when the Pope’s staff brought forth green leaves would Tannhäuser be forgiven. Knowing this to be impossible, the weary minnesinger has resolved to return to Venus. As she appears, however, a funeral procession enters, carrying Elisabeth’s body on a bier. She has gone to heaven to pray for Tannhäuser’s soul. Pilgrims enter, carrying a priest’s staff bearing green leaves: Tannhäuser’s soul has been saved.

Wagner had intended to call his opera Der Venusberg – the German term for a certain part of the female anatomy. Medical students and professors, with “a predilection for that kind of obscene joke”, made fun of the title, and Wagner, disgusted, changed the name.2 Nevertheless, Tannhäuser remained a scandalous work, and for its 19th century admirers, the quintessence of decadence and sensuality. Baudelaire was intoxicated by it like a drug. Oscar Wilde’s vampiric aesthete Dorian Gray “listen[s] in rapt pleasure to Tannhäuser and seeing in the prelude to that great work of art a presentation of the tragedy of his own soul”.3 Swinburne and the Pre-Raphaelites, Aubrey Beardsley, and even Aleister Crowley, self-styled “wickedest man in the world”, created works inspired by it.4 Freud’s “On the Universal Tendency to Debasement in the Sphere of Love”, Alex Ross suggests, is “a gloss on Tannhäuser”.5 Paul Dawson-Bowling6, meanwhile, credits Wagner with the sexual revolution: “The answers and truths about erotic passion which Tannhäuser encouraged overturned the ‘denial of man’s primordial animal nature’ which had been a life-diminishing ordinance of Western civilisation for almost two millennia.”

Tannhäuser was first performed in Dresden in 1845; sources say that Wagner was called onto the stage after each act, and the musicians of the orchestra and more than 200 young people, torches in hand, accompanied him home, and serenaded him with pieces from his works and those of Meyerbeer. But Wagner considered the opening night a depressing failure. Tichatschek, the tenor who created the title rôle, could not act the part; he was “incapable of all dramatic seriousness, and [his] natural gifts only fitted him for joyous or declamatory accents, and [he] was totally incapable of expressing pain and suffering”.7 Schröder-Devrient was too matronly for the voluptuous Venus, and her portrayal “sketchy and clumsy”. The critics “with unconcealed joy, attacked it as ravens attack carrion thrown out to them”.8 Wagner himself was even called a Catholic reactionary – rather surprising, given the Pope is Tannhäuser’s antagonist; Venus is more forgiving than the earthly representative of the supposed religion of mercy. A much-curtailed version was performed a week later, to an almost empty but appreciative house; a third performance, to a full house. Nevertheless, Tannhäuser became a piece for connoisseurs and intellectuals, rather than for the general opera-going public.

The music

Tannhäuser has perhaps Wagner’s highest concentration of ‘hit tunes’. The overture is famous; it made Wagner celebrated in Paris long before the 1861 fiasco. According to the composer9, it depicts Tannhäuser, “Love’s Minstrel”, lured into Venus’s domain at night; he succumbs to her temptations; but, as dawn approaches and the Pilgrims’ Chant resounds, the spell of Venusberg is broken, and Tannhäuser is redeemed from its impious allure. “Both dissevered elements, both soul and senses, God and Nature, unite in the atoning kiss of hallowed love.” Queen Victoria, no less, called it “A wonderful composition, quite overpowering, so grand, & in parts wild, striking and descriptive”.

Act I opens in the Venusberg, where the goddess reclines on a couch; Tannhäuser, once her admirer, is sated with endless pleasure, and wants to return to the mortal world and to pain. For the Paris production, Wagner wrote a big ballet depicting a ‘Bacchanale’, verging on the pornographic: youths “pair and mingle” with naiads, Bacchantes “excite the lovers to increasing licence”, and “the revellers rush together with ardent love-embraces”, before Cupids shower them with arrows.

Act I moves swiftly, even if the scene with Venus (petulant and blowsy in the Dresden version, erotically Isoldean in the Paris revision) shows Wagner’s regrettable fondness for long, static dialogue scenes of limited melodic interest. Bored of this, Tannhäuser calls on the Virgin Mary, and he finds himself in a green valley. The two realms have different sound-worlds: the Venusberg is lush and overheated, chromatic and cloying, while the mortal world is clearer and simpler. A shepherd boy tootles on a pipe, and sings a gentle, unaccompanied song; and a band of pilgrims set out to Rome (the first iteration of the famous chorus). Tannhäuser prays at a shrine to the Virgin, and is recognised by the Landgrave and his minnesingers, amidst a hullaballoo of hunting horns and dogs, “latrant, mugient, reboatory”. Wolfram’s phrase “Gegrüsst sei uns, du kühner Sänger”, welcoming Tannhäuser, is lovely and warm, and the stretta is jolly.

Act II is set in the Hall of Song, and is, for the most part, appropriately enough, a series of conventional grand opera numbers: the prima donna’s aria di sortita (Elisabeth’s Greeting to the Hall, “Dich, teure Halle”, whose upward moving phrase expresses her joy); a duet for the soprano and tenor; and a grand march (the brilliant, pompous, and rather wonderful Entry of the Guests).

The Landgrave’s prosy address puts a dampener on things; nearly five minutes long, it overstays its welcome. So does the Singers’ Contest itself; the first time I heard Tannhäuser, it induced catatonic boredom. Several poets recite poems about what love means to them – unsullied by carnal desire, admiring from afar, but never consummated – while Tannhäuser, turned literary critic, dismisses their odes as adolescent hackwork, and their imagery as puerile. Wagner’s10 intention was to “force the listener, for the first time in the history of opera, to take an interest in a poetical idea, by making him follow all its necessary developments. For it was only by virtue of this interest that he could be made to understand the catastrophe, which in this instance was not to be brought about by any outside influence, but must be the outcome simply of the natural spiritual processes at work.” Wagner’s own wife thought the music made “a really feeble impression”, and even Wagner aficionados like Newman have found it drags. Listen to it enough times, though, and familiarity will make it more palatable.

Fed up with these insipid idylls, written by virgins who would never do anything quite so vulgar as have it off with a woman, Tannhäuser tells them to go to the Venusberg. Horrified by such ungentlemanly behaviour, the ladies swoon, and the gentlemen pull out their swords. The finale that follows, all 20-odd minutes of it, is magnificent, particularly the plaintive adagio section, which rises to a mighty climax, and the stretta. “Nach Rom!”

Act III takes place several months later, in the valley of Act I, in autumn. The superb prelude depicts Tannhäuser’s weary pilgrimage to Rome; one can hear the splendour of the Eternal City – and his misery.

Before Tannhäuser appears, however, there are three of the opera’s most beautiful, and two of all opera’s most famous, ‘numbers’: the majestic Pilgrims’ Chorus, one of the first Wagner pieces to hook me two decades ago; Elisabeth’s prayer “Allmächt’ge Jungfrau”, suffused with great calm; and Wolfram’s Song to the Evening Star (i.e., Venus!), “O du, mein holder Abendstern”, a beautiful romance showcasing the baritone voice.

Tannhäuser’s Rome Narration is one of Wagner’s early ‘advanced’ passages, 15 minutes of quasi-recitative where the musical interest is in the orchestra. The end is rather hurried: Tannhäuser, knowing he is damned, resolves to return to Venus; the goddess appears (or not, depending on the version); a funeral procession enters, carrying Elisabeth’s body on a bier (or not, again); Tannhäuser dies; and pilgrims enter, carrying a priest’s staff bearing green leaves: Tannhäuser’s soul has been saved. The opera ends with a triumphant, moving, luminous and oceanic reprise of the Pilgrims’ Chorus, “Heil! Heil! Der Gnade Wunder Heil!”.

Shortly before he died, Wagner intended to revise the opera once more; he felt that he still owed the world a Tannhäuser. Unlike the later music dramas, it is a work where the parts are greater than the whole – but many of those parts are inspired.

How Paris saw Tannhäuser

In 1860, Napoleon III gave orders for the Paris Opéra to stage Tannhäuser. Princess Metternich had seen it in Dresden, and “spoke in such enthusiastic terms in favour of it that the Emperor at once promised to give orders for its production”.11 After 164 rehearsals – the conductor Dietsch could not grasp Wagner’s tempi – Tannhäuser was finally performed, on 13 March 1861: “a disastrous date in Wagner’s career”, La Causerie12 suggested.

“There was neither serious opposition nor passionate protest in the audience, but an even worse and more disappointing attitude, that is, a general irony,” La Causerie13 wrote. “He wasn’t even deemed worthy of being discussed as a musician, for once again, the unfortunate maestro received nothing but laughter and sarcasm.”

In a letter the day after the premiere,14 Hector Berlioz wrote: “God in heaven, what a performance! Everyone was laughing. The Parisians were revealed yesterday in a totally new light. They laughed at the bad musical style, they laughed at the depravities of the farcical orchestration, they laughed at the silliness of an oboe. They finally understood that there is such a thing as style in music. As for the horrors, they were hissed splendidly.”

Prosper Mérimée15, who was there, called the opera “a colossal bore. It seems to me that tomorrow I could write something similar by drawing inspiration from my cat walking on the keys of a piano. The performance was very curious… Eevryone was yawning; but at first, everyone wanted to appear as if they understood this wordless puzzle. Princess Metternich made a tremendous effort to pretend to understand, and to start the applause – which didn’t come. She even broke her fan in the attempt. It was rumoured in her box that the Austrians were taking revenge for Solferino [the French victory over the Austrians in 1859]… The fiasco is enormous!”

La Causerie16 condemned the persecution of innovation: “You start barking like a pack of dogs in the service of blind Prejudice, and with prearranged laughter, with shushes rehearsed the day before, with systematic conversations, coughs and sneezes noted on the cabal’s score, you deliberately muffle this new voice that wants to be heard!”

Both the Opéra’s subscribers and the musical press had made up their mind beforehand. Wagner had proclaimed that Tannhäuser would be followed by Lohengrin and his other works, including Tristan und Isolde. “The Parisian public considered a somewhat unsettling threat,” Alphonse Royer17, director of the Opéra, recalled. “One of the subscribers asked Wagner if the parade would last long; he replied: ‘Forever!’ He couldn’t have been less diplomatic. Consequently, the death sentence of Tannhäuser was pronounced before the curtain rose.” Critics like Paul Bernard18 (Le Ménestrel) objected to the imposition of “the music of the future”, which called for “the overthrow of consecrated ideas, for contempt of form; that wants to establish a neo-musical system, and that would gladly break yesterday’s idols to say: I am the truth!” In the same publication, a week previously, J.-L. Heugel19 stated that Wagner’s system would lead to the complete negation of true music.

Auber, asked his opinion, said: “It’s like reading a book without full stops or periods, without taking a breath.”20 Or (according to Mérimée21) that it was like Berlioz without melody: “How bad it would be if it were actually music!” Gounod said it “interested him very much from a grammatical point of view”.22 Nevertheless, according to Wagner, Gounod “energetically championed my cause in society”, and even remarked: “May God grant me such a failure!”23 The grateful German presented Gounod with the score of Tristan und Isolde.

Barring a few pieces – Tannhäuser’s strophes praising Venus, the Pilgrims’ chorus, the knights’ march in Act I, the duet, the septet and the first part of the finale in Act II, Wolfram’s romance to the star – rightly considered grand and beautiful, French musicologists found Tannhäuser boring and formless, conceived, Chouquet24 wrote, according to a retrograde and anti-dramatic system.

Benoît Jouvin (Le Figaro)25 thought Tannhäuser lacked clearly defined musical ideas: “A dragging and vague melody floats on a sea of boundless harmonies. It’s the great Ocean of monotony; it’s a despairing and greyish infinity, where one hears the dull lapping of the seven notes of the score falling until the end of the score. It is neither song, nor recitative, nor rhythm, nor sustained note.” Heugel26 (Le Ménestrel) summed up the score as “a loud and brash orchestration, craving effects and dissonances … an instrumentation so complex that it bordered on excessive and overpowering … the paroxysm of the violin, and above all … an excess of recitatives that induced the most prolonged torpor in the most dangerous way for the health of the listeners”. The orchestration was “the negation of temperance, charm, harmony”, “a desolate avalanche of notes that mercilessly descends upon this musical desert that M. Richard Wagner has made his grand backdrop”.27

Nor was the libretto to French taste. “For any French reader or spectator, what Richard Wagner’s poems lack the most is the art that brings characters to life with a real vitality, animating them with human emotions capable of evoking similar ones in us, be it tenderness or terror, joy or pity,” wrote Paul Smith (Revue et gazette musicale de Paris)28. “Tannhäuser is no exception: it leaves us perfectly indifferent, and we are unsure how it contributes to the system, where dramatic action should be the main goal.” Even La Causerie29, indignant at the cabal against Wagner, doubted whether the libretto contained sufficient dramatic elements to sustain interest over three acts. “Perhaps yes, for a German audience that willingly feeds on vagueness and abstractions.” But it did not “contain in any way the elements of action constituting the essence of lyrical drama as we understand it in France”.

Wagner knew who to blame: “The press … was entirely in the hands of Meyerbeer”.30 It was a furphy, but it contributed to his smear campaign against the great composer. The otherwise superb Richard Burton miniseries even shows Meyerbeer (Vernon Dobtcheff) in the audience, gloating over Wagner’s failure. Meyerbeer was in Prussia at the time, and his diary (15 March)31 shows he sympathised with Wagner: “Such an unusual demonstration of dissatisfaction with a work which, in any case, is so admirable and talented, would appear to be the result of a cabal and not a genuine popular verdict, and in my opinion will only stand the work in good stead at later performances.”

Wagner32 comforted himself with the reflection “that in the end a favourable view of my opera prevailed, inasmuch as the intention of my opponents had been to break up this performance completely, and this they had found it impossible to do”.

But worse was to come. The Jockey Club sabotaged the second and third performances (18 and 24 March). It was their habit to dine during Act I, and to arrive at the Opéra only in the middle, to ogle the ballerinas. Wagner, however, had placed the ballet at the start of Act I. He thought the ‘Bacchanale’ “would give the staff of the ballet a choreographic task of so magnificent a character that there would no longer be any occasion to grumble at me for my obstinacy in this matter”.33 (Wagner was too stubborn; it would have been easy to write another ballet in Act II, between the entrance of the guests and the singers’ tournament.) The Jockeys, angry that they were deprived of their entertainment, retaliated by blowing flageolets and whistles. There were brawls in the audience, too; the third night’s performance was twice interrupted by fights lasting a quarter of an hour each.34

“The second performance of Tannhäuser was noisier than the first,” Berlioz35 told his son. “There was less laughter – it was fury. They brought the house down hissing and booing, this in spite of the presence of the Emperor and Empress, who were in their box. The Emperor is having a good time. On the way out, on the staircase, people were openly calling the unfortunate Wagner a scoundrel, an impertinent, a lunatic. At this rate, one of these days the performance will be brought to a halt and that will be that. The press is unanimous in wiping him out. As for me, I am cruelly avenged.” He was piqued that the Opéra had staged Wagner’s work before his Troyens.36

Refusing to have his artists subjected to such indignities, Wagner withdrew his work, and returned to Germany. He claimed, however, that “this by no means exquisite performance of my work met with louder and more unanimous applause than ever I experienced personally in Germany”.37

The received view, as set out in Félix Clément’s Dictionnaire des opéras38, the standard reference work, was that several scenes were coarse in a way that revolted French audiences, and the ending was shameful; bar a handful of numbers, and despite a powerful sense of harmonic and instrumental effect, the rest of the score was either murky or childish, but certainly very boring.

But the French, in fact, were intrigued by Wagner’s music. The Théâtre-Lyrique and the Opéra-Comique both intended to produce Tannhäuser; Muscard and Pasdeloup included Tannhäuser in their concerts; and Pauline Viardot and Roger (the stars, incidentally, of Meyerbeer’s Prophète a dozen years before) performed pieces from Tannhäuser.39

The battle was by no means lost; Wagner’s music would influence French composers, including Massenet, Saint-Saëns, and Reyer. But his operas would not be performed in Paris for 30 years, and Tannhäuser not until 1895.

Suggested recordings

Listen to: Birgit Nilsson (Elisabeth), Wolfgang Windgassen (Tannhäuser), Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (Wolfram), and Theo Adam (Hermann), with the Deutscher Oper Berlin orchestra and chorus, conducted by Otto Gerdes; Berlin, 1968; Deutsche Gramophon. (Dresden version)

Watch: Eva Marton (Elisabeth), Richard Cassilly (Tannhäuser), Bernd Weikl (Wolfram), Tatiana Troyanos (Venus), and John Macurdy (Hermann), with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra conducted by James Levine; New York, 1982.

- Victor Cochinat, ‘La cabale contre Richard Wagner’, La Causerie, 17 March 1861: « La soirée du 13 mars 1861 marquera comme une date néfaste dans la carrière du compositeur Richard Wagner… Bref, le Tannhäuser est tombé lourdement et presque sans défense, dans cette soirée de mercredi dernier, qui doit être pour Richard Wagner la plus amère, la plus cruelle déception qu’il ait jamais éprouvée dans sa vie d’artiste. » ↩︎

- Richard Wagner, My Life, authorised translation, London: Constable, 1963, pp. 363-64. ↩︎

- Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1890, ch. XI. ↩︎

- Alex Ross, Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music, London: 4th Estate, 2020, pp. 122-24, 187, 305-06. ↩︎

- Ross, op. cit., p. 318. ↩︎

- Paul Dawson-Bowling, The Wagner Experience: And Its Meaning to Us, Old Street Publishing, 2013. ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, p. 375. ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, p. 378. ↩︎

- Richard Wagner, “Overture to Tannhäuser”, 1852, in On Music and Drama, trans. H. Ashton Ellis, New York: Dutton, 1964. ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, p. 369. ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, p. 736. ↩︎

- Cochinat, op. cit.: « La soirée du 13 mars 1861 marquera comme une date néfaste dans la carrière du compositeur Richard Wagner. » ↩︎

- Cochinat, op. cit.: « Il n’y a eu ni opposition ni sérieuse ni protestations passionnées dans l’auditoire, mais une attitude pire encore entre les plus décevantes, c’est-à-dire une ironie générale… On n’a pas daigné seulement le traiter comme un musicien digne d’être discuté, car, encore une fois, il n’a recueilli, l’infortuné maître, que le rire et le sarcasme. » ↩︎

- David Cairns, Berlioz, Vol. II: Servitude and Greatness 1832–1869, Allen Lane / the Penguin Press, 1999, p. 662. ↩︎

- Prosper Mérimée, Lettre à une inconnue, March 1861, operas (artlyriquefr.fr) : « Un dernier ennui — mais colossal — a été Tannhäuser… Il me semble que je pourrais écrire demain quelque chose de semblable en m’inspirant de mon chat marchant sur le clavier d’un piano. La représentation était très curieuse… Tout le monde bâillait ; mais d’abord, tout le monde voulait avoir l’air de comprendre cette énigme sans mot. La princesse de Metternich se donnait un mouvement terrible pour faire semblant de comprendre, et pour faire commencer les applaudissements — qui n’arrivaient pas. Elle y brisa son éventail. On disait sous sa loge que les Autrichiens prenaient la revanche de Solférino… Le fiasco est énorme ! » ↩︎

- Cochinat, op. cit. : « C’est pour nous un besoin d’exhaler notre indignation contre ces injustices, ces violences matérielles et ces persécutions barbares qui assaillent toute œuvre nouvelle coupable du péché d’innovation et d’irrévérence envers la routine…

« Quoi ! vous vous dites les propagateurs des pensées nouvelles, vous vous donnez comme des gens affamés d’idées neuves et soupirant après le nouveau, et lorsqu’un artiste a cette audace insigne de sortir un instant du cercle convenu, du cadre banal et usé dans lesquels se meuvent vos vieilles machines, vous n’avez pas assez de haros pour refouler cet homme dans l’obscurité !

« Vous vous mettez à aboyer comme une meute au service du Préjugé aveugle, et avec des rires concertés à l’avance, des chut ! réglés la veille, des conversations systématiques, une toux et des éternuements notés sur la partition de la cabale, vous couvrez avec préméditation cette voix nouvelle qui veut se faire entendre ! » ↩︎ - operas (artlyriquefr.fr) ↩︎

- Paul Bernard, Le Ménestrel, 24 March 1861 : « Comment espérer que des organisations nerveuses et délicates puissent pardonner trois heures d’ennui à l’auteur qui vient d’Allemagne , imposé par des circonstances plus ou moins véridiques, et qui arrive enfin à l’épreuve décisive, après avoir fait suer sang et eau au premier théâtre musical du monde, pendant trois ou quatre mois de répétitions consécutives, pour prouver quoi? — que tout ce qui s’est écrit en musique, jusqu’à ce jour, tout ce qui est signé Mozart, Rossini, Weber, Meyerbeer, Halévy, Verdi, — je ne parle que du genre dramatique, — est l’enfance de l’art, et que si l’on marche longtemps sur cette voie, c’est tout au plus si les nourrices de nos petits-fils daigneront bercer leurs nourrissons avec le serment de Guillaume Tell ou la bénédiction des poignards des Huguenots!

« Étonnez-vous donc, après cela, de l’espèce de révolte occasionnée dans la pléiade artistique et critique de Paris, à l’audition d’une œuvre qui pose pour le renversement des idées consacrées, pour le mépris de la forme ; qui veut établir un système néo-musical, et qui briserait volontiers les idoles de la veille, pour dire : la vérité, c’est moi ! Étonnez-vous donc surtout de l’espèce de colère ironique attachée à cette manifestation contraire, quand on voit l’extension que prend cette tendance de l’autre côté du Rhin, et qu’on se sent envahir par un brouillard froid qui vous pénètre de torpeur.

…

« Serrons les rangs chez nous, nous autres vrais croyants de la vieille foi, et fermons notre porte, après l’avoir entr’ouverte un instant; oui, fermons-la à ces rénovateurs, à ces iconoclastes, à ces utopistes insensés qui cherchent l’Icarie musicale, mais qui ne la trouveront pas à Paris, Dieu merci ! » ↩︎ - J.-L. Heugel, Le Ménestrel, 17 March 1861 : « Hé bien, c’est contre cette énorme prétention que Paris proteste et doit protester. Nous avons compris ce qui était compréhensible dans l’œuvre du Tannhauser; ce que nous avons condamné sans pitié, dans le présent et l’avenir, c’est le détestable système intronisé dans l’ensemble de la partition, au double point de vue du chant et de l’orchestre, système qui n’abourait à rien moins qu’à la négation complète de la vraie musique. » ↩︎

- Figaro, 21 March 1861: « C’est comme si on lisait, sans reprendre haleine, un livre sans points ni virgules. » ↩︎

- Mérimée, op. cit.: « Auber, interrogé, prétend que c’est du Berlioz sans mélodie : « Comme ce serait mauvais si c’était de la musique ! » » ↩︎

- Figaro, op. cit. ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, pp. 770–71. ↩︎

- Gustave Chouquet, Histoire de la musique dramatique en France, 1873: « La marche des pèlerins, l’introduction au tournoi des chanteurs, les strophes du chevalier au 1er acte, le duo du chevalier et d’Élisabeth au 2e acte et la mélodie de Wolfram, au 3e acte, sont les seuls morceaux qui aient une forme arrêtée ; les autres parties de l’ouvrage sont conçues d’après un système rétrograde et antidramatique. » ↩︎

- B. Jouvin, Le Figaro, 21 March 1861: « Ce qu’on cherche vainement dans la partition de Tannhäuser, indépendamment de la mélodie, telle que la conçoit l’oreille façonnée aux chefs-d’œuvre du passé, c’est un dessin musical nettement arrêté, une ligne suivie, un contour saillant ; quelque chose, en un mot, où l’esprit se suspende, où l’imagination se repose. Rien ! Une mélopée traînante et vague flotte sur une mer d’harmonies sans rivages. C’est le grand Océan de la monotonie ; c’est un infini désespérant et grisâtre, où l’on entend le morne clapotement des sept notes de la gamme qui tombent jusqu’à la consommation de la partition. Ce n’est ni du chant, ni du récitatif, ni du rhythme, ni du point d’orgue. Gluck est aussi étranger à ce style-là que Rossini lui-même. La phrase de M. Wagner, diffuse jusqu’au galimatias ou ténue jusqu’à l’invisible, est un fil sans fin, que le musicien enchevêtre dans la trame toujours très savante de ses modulations sans issue. Figurez-vous une bobine qu’on déviderait durant toute une soirée, une bobine inépuisable destinée à faire pendant à la bouteille inépuisable d’un autre grand homme, le prestidigitateur Robert-Houdin, un voisin heureux de notre grand Opéra, les soirs où l’on y donnera le Tannhäuser.

« A force de brasser des notes et de remuer des harmonies jusqu’en leurs profondeurs les plus reculées, –et cela avec un incontestable savoir et une grande sûreté de main, – il arrive à M. Wagner de trouver des effets d’instrumentation entièrement neufs, des oppositions de couleurs, des résolutions inattendues, des agrégations de sons qui produisent un choc original. Mais il n’en faut rien conclure en faveur d’un système qui semble s’être proposé l’absurde pour fin et la barbarie pour idéal. Un jour peut-être, il naîtra un homme de génie qui, appliquant à des œuvres logiques et rayonnantes du feu de l’inspiration quelques-uns des effets entassés dans le Tannhäuser sans discrétion et sans goût, leur accordera le droit de bourgeoisie dans l’art et prononcera sur ce chaos la grande parole : Fiat lux ! A ce point de vue, mais au profit d’un autre, M. Richard Wagner aura apporté sa pierre à la musique de l’avenir. Il sera le manœuvre chargé de voiturer le moellon avec lequel un architecte sublime doit bâtir une Notre-Dame de Paris. » ↩︎ - Heugel, Ménestrel, op. cit.: « Or, interrogeons le public de mercredi dernier, à l’Opéra. S’est-il ému une seule fois durant toute la soirée? A défaut de cette émotion profonde qui enlève une salle entière, a-t-il été charmé par des mélodies limpides, des harmonies suaves, onctueuses, des effets piquants, des rhythmes nouveaux? Non, rien de tout cela.

« Disons-le hautement : il a été énervé, surexcité par une orchestration stridente, insatiable d’effets et de dissonances, par une instrumentation complexe jusqu’à l’abus des détails et de la force permanente, par le paroxisme de la chanterelle, et surtout par une intempérance de récitatifs qui porte à la torpeur la plus prolongée et de la façon la plus dangereuse pour la santé des auditeurs. » ↩︎ - Ibid: « Quant à l’orchestration, nous l’avons dit et le public tout entier le répétait de loge en loge, de stalle en stalle, c’est la négation de la tempérance, du charme, de l’harmonieux ; mais, en revanche, une désolante avalanche de notes qui s’abat sans pitié sur ce désert musical dont M. Richard Wagner a fait sa grande toile de fond. » ↩︎

- Paul Smith, Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, 17 March 1861: « Pour tout lecteur ou spectateur français, ce qui manque le plus aux poëmes de Richard Wagner, c’est l’art qui fait vivre les personnages d’une vie réelle, qui les anime de sentiments humains susceptibles d’en éveiller en nous d’analogues, tendresse ou terreur, joie ou pitié. Tannhäuser ne déroge pas à la règle : il nous laisse parfaitement insensibles, et nous ne savons en quoi il profite au système, dont l’action dramatique doit être le but principal. » ↩︎

- Léon Leroy, La Causerie, 17 March 1861 : « Voilà le canevas sur lequel Richard Wagner a écrit les trois actes de son opéra. Ce sujet renferme-t-il maintenant les éléments dramatiques suffisants pour soutenir l’intérêt trois actes durant ? Vis-à-vis d’un public allemand qui se nourrit volontiers de vague et d’abstractions, peut-être oui ; mais, pour nous, c’est tout autre chose, et, si habilement que l’auteur ait disposé ses épisodes, quelque tact qu’il ait pu déployer dans la conduite de son drame, – encore est là une question à débattre, – il n’a pas réussi à tirer un parti avantageux, pour le musicien, de ce sujet légendaire qui, d’ailleurs, ne nous semble pas, nous le répétons, renfermer en quoi que ce soit les éléments d’action constituant l’essence du drame lyrique tel que nous le comprenons en France. » ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, p. 757. ↩︎

- Robert Ignatius Letellier, Giacomo Meyerbeer: A Critical Life and Iconography, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2018, p. 379. ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, p. 764. ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, p. 753. ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, p. 767. ↩︎

- Cairns, op. cit., p. 662. ↩︎

- Cairns, op. cit., p. 651. ↩︎

- Richard Wagner, “Tannhäuser in Paris”, in Wagner on Music and Drama, p. 48. ↩︎

- Félix Clément, Dictionnaire des opéras, 1869: « La pensée de la légende est une pensée de moralité. L’auteur du poème n’a pas semblé le comprendre. Plusieurs scènes sont d’une grossièreté qui devait révolter un public français, et le dénouement est honteux. La musique, conçue dans un système plus littéraire que musical, n’a pas tenu les promesses que des prôneurs exaltés et presque fanatiques avaient fait espérer. A l’exception de l’ouverture, de la marche des pèlerins, des strophes du chevalier au premier acte, du duo avec Elisabeth, de la romance de Wolfram au troisième acte, de quelques autres passages qui accusent une forte organisation musicale, un sentiment puissant de l’effet harmonique et instrumental, tout le reste de la partition est ou ténébreux, ou puéril, mais assurément fort ennuyeux. » ↩︎

- Wagner, My Life, p. 771. ↩︎

19 thoughts on “281. Tannhäuser (Wagner)”