- Opera seria in 1 act after The Bacchae by Euripides

- Composer: Hans Werner Henze

- Libretto: W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman

- First performed: Salzburg, 6th August 1966, in a German translation as Die Bassariden, conducted by Christoph von Dohnányi.

- First performance in English: Sante Fe Opera, USA, 7th August 1968, conducted by Henze.

Characters

| DIONYSUS | Tenor | Loren Driscoll |

| PENTHEUS, king of Thebes | Baritone | Kostas Paskalis |

| CADMUS, founder and former king of Thebes | Bass | Peter Lagger |

| TIRESIAS, an old blind prophet | Tenor | Helmuth Mulchert |

| Captain of the Guard | Baritone | William Dooley |

| AGAVE, Cadmus’s daughter, mother of Pentheus | Mezzo | Kerstin Meyer |

| AUTONOE, daughter of Cadmus | Soprano | Ingeborg Hallstein |

| BEROE, an old slave, once nurse to Semele and Pentheus | Contralto | Vera Little |

| Bassarids, citizens of Thebes, guards, servants | Chorus |

SETTING: Ancient Thebes

A renegade modernist

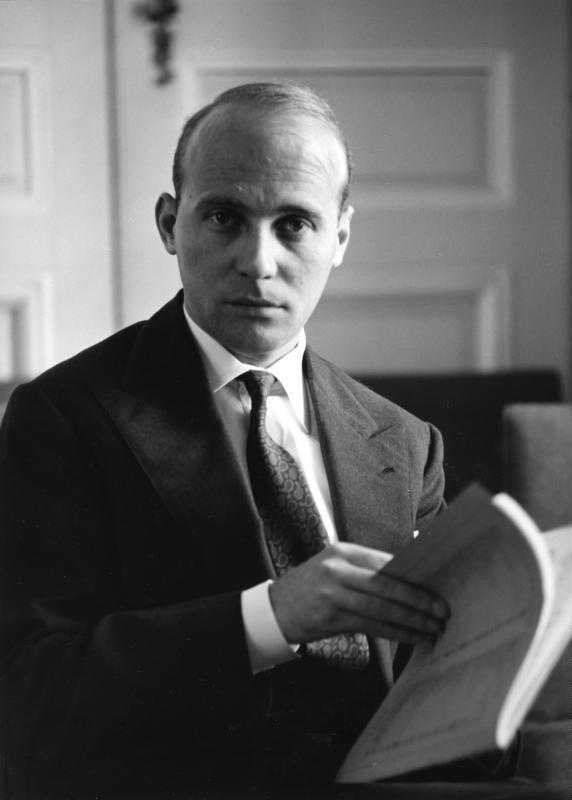

Hans Werner Henze. 7.6.1960 Köln Schloss Brühl Eröffnung der Internationalen Meisterkurse der Staatl. Hochschule für Musik. Source: Wikipedia.

Hans Werner Henze (1926–2012) — Communist and gay — was the most prolific and politically committed of late 20th-century opera composers. He was a renegade among late 20th century composers: in an age when the arts had become inward-looking, theoretical and dogmatic, he never forgot that music should speak to the public. Indeed, while Pierre Boulez called for opera houses to be blown up, Henze proclaimed that “Opera belongs to all”:

The notion that opera is ‘bourgeois’ and an obsolete art form is itself one of the most outdated, tedious and musty notions.1 […] This art form contains riches that are among the most beautiful inventions of the human spirit. They belong to all people; they were not written for the ruling class, but in a spirit of human brotherhood.

After World War II, there was a split between the music-loving public and the modern composers who treated the public with contempt, and wrote music for small, tight circles of the intelligentsia. Modern music was dominated — under “dictatorial control” — by the Darmstadt School, with its “technocratic conception of art, dodecaphony’s mechanistic heresy, which became official doctrine there”2; by the self-proclaimed genius Karlheinz Stockhausen; and by Boulez, who rejected all music that was not in the style of Anton Webern: “All art of the past must be destroyed.” Instead of engaging listeners, modernist composers deliberately destroyed classical music’s connection with its audience; enjoyment was a sign of failure. Henze saw it from within:

Everything had to be stylized and made abstract: music regarded as a glass-bead-game, a fossil of life.3 Discipline was the order of the day. Through discipline it was going to be possible to get music back on its feet again, though nobody asked what for. Discipline enabled form to come about; there were rules and parameters for everything. Expressionism and (left-wing) Surrealism were mystically remote; we were told that these movements were already obsolete before 1930, and had been surpassed. The new avantgarde would reaffirm this. The audience, at whom our music was supposed to be directed, would be made up of experts. The public would be excused from attending our concerts; in other words, our public would be the press and our protectors.

The existing audience of music-lovers, music-consumers, was to be ignored. Their demand for ‘plain-language’ music was to be dismissed as improper. (A wise man does not answer an impertinent questioner.) On top of this we had to visualise the public as illiterate, and perhaps even hostile. If it was our fate that we, the élite, were exposed to these philistines, we were to arm ourselves with contempt and the smug feelings of martyrs. Any encounter with the listeners that was not catastrophic and scandalous would defile the artist, and would mobilise mistrust against us. At best one could approach the public with enigmas, without providing solutions. As [philosopher Theodor] Adorno decreed, the job of a composer was to write music that would repel, shock, and be the vehicle for ‘unmitigated cruelty’. At the same time the composer had to allow himself to be guided in his idiosyncrasy by taste, the truest seismograph of historical experience. Thus spake Adorno; this was supposed to be the point of departure for the new international generation of composers.

Adorno also thought that popular music (jazz, folk songs, the Beatles) led to fascism.

The problem with modern music, Henze believed, was that it was depoliticised, “totally mechanised and incapable of expressiveness”4, and that it “never reached the majority of listeners — for whom a composer should after all be writing”. As a Communist, Henze believed that music had a political purpose, not merely an aesthetic one: “through music it would be possible to bring about intellectual and moral change, and democratic musical thinking”.5 Music that failed to reach the public was music that failed to communicate, and to speak to the times. Henze suspected that the Darmstadt School’s “attempt to make music non-communicative”, formalist and apolitical, “had something to do with the ruling class’s belief that art is a thing apart from life, better kept that way, and without any social dimension”; Darmstadt’s ‘non-communicative’ tendency was “vigorously promoted … to prevent people from seeing music as simple, concrete and comprehensible communication between human beings”.6

Henze sensibly rejected the total serialism and the cold rationalism of the Darmstadt School, and sought to write music that was expressive and dramatic. His solution was eclecticism, combining modern techniques with the best of what the past offered. He turned his back on both the dogmas of Darmstadt, where Boulez presided over the scholastic sterility of serialism, and on conservative West Germany, where his landlady informed on him to the police for bringing home a lover. And, as German composers, Handel and Meyerbeer among them, had done since the seventeenth century, he went to Italy.

“I felt I had the chance to do something real, to forget what I had suffered, and to listen to what was around me, to study people’s interests in a revolutionary country with a classical culture.”7

There, he discovered Neapolitan folksong8, and embraced tonality, Stravinskyan neoclassicism, and Romantic textures9.

“Subsequently I have attempted in almost every new work to make a synthesis between popular musical traditions and the fully evolved style of our own age.”10

Thus, the operas of this period — notably Der Prinz von Homburg (1960), Elegy for Young Lovers (1961), and Der junge Lord (1965) — are modernist engagements with 19th-century Italian opera:

“the angelic melancholy of Bellini, the sparkling brio of Rossini, the passionate intensity of Donizetti, combined and drawn together by Verdi’s robust rhythms, his hard orchestral colours and unforgettable melodic lines.”11

Henze’s commitment to ‘reactionary’ musical elements angered the avant-garde. The Darmstadt School accused Henze of selling out to public taste.12 Theodor Adorno believed Henze’s music was “not chaotic enough”13; the intolerant Luigi Nono smashed Meissen porcelain in disgust when the composer’s name was mentioned; the conductor Hermann Scherchen objected to the presence of arias in one early opera (“But, my dear, we don’t write arias today”); and Boulez walked out of a concert, offended by the triads in a vocal suite14. But, The Gramophone observed:

“At a time when the musical world was either preoccupied with the libertarianism of, say, Stockhausen and Cage, or the order and totalitarianism of the serialists, Henze’s balanced approach to tradition and modernity makes a lot of sense.”15

The Bassarids

The Bassarids is an adaptation of Euripides’ last and perhaps greatest tragedy, The Bacchae (405 BCE) — in which the god is not in the machine, restoring order at the end of the play, but its antagonist, punishing and destroying those who do not recognise his godhood. The young Dionysus has come to Thebes, but the king, his cousin Pentheus, denies his divinity, and forbids his cult. The god retaliates by driving the royal family mad: his aunts become frenzied Bacchantes, and tear Pentheus to pieces.

The Bacchae, Vellacott16 argues, concerns “the danger to society arising from the cult of mass-emotion”, “the growth of mass hysteria, the cult of violence, the spread of credulity, the ‘flight from reason’”. Vellacott’s translation appeared in the 1950s; he would have had Nazi Germany in mind. But destructive Dionysian urges threaten the modern world, too: not only in populism and the mistrust of experts, but in social media, which Max Fisher (The Chaos Machine, 2022) describes as “a machine engineered to distort reality through the lens of tribal conflict and pull users toward extremes” — such as the mob mentality of pile-ons and cancel culture.

The Bassarids — a commission for the Salzburg Festival — marked Henze’s return to the German tradition:

The road from Wagner’s Tristan to Mahler and Schoenberg is far from finished, and with The Bassarids, I have tried to go further along it.17 I am not prepared to relinquish what the centuries have passed on to us. On the contrary, ‘One must also know how to inherit; inheriting, that, ultimately, is culture.’ That was Thomas Mann’s view, and I willingly subscribe to it.

The librettists, the poets Auden and Kallman, had insisted that Henze “make his peace” with Wagner, and see Götterdämmerung in Vienna (which Henze said brought him no joy).18 Instead, Henze modelled the work on Mahler. The “through-composed large-scale form of opera” followed the rules of the four-movement symphony:

A sonata movement is followed by a scherzo — a series of bacchanalian dances with a calm vocal ensemble as trio.19 The third movement is an adagio with fugue, interrupted by an intermezzo — the satyr play, an opera within the opera; the fourth, with its Ash Wednesday mood, is a passacaglia.

Like other late twentieth century operas (for example, Ginastera’s Bomarzo or Penderecki’s Teufel von Loudun), The Bassarids is thought-provoking and powerful, but it is not tuneful. (When I searched for “Henze Bassarids”, Google suggested that I hum it, which would be difficult.) But as Henze explains:

This work is a tragedy, a funeral symphony, a requiem (ending with a gloria).20 Its goal is truth, and truth is serious, difficult and cruel — not culinary.

It is an expressionist work in which an enormous orchestra — sometimes overwhelmingly loud, discordant and strident, elsewhere almost chamber music, with passages of shimmering beauty — depicts hysteria and terror. The most effective passages include Movement III, part II, where Dionysus takes the deluded Pentheus out of Thebes at twilight, and the hunt of the Maenads, with ferocious Xenakis-like percussion.

At its première, Die Bassariden (sung in German) was “less than warmly received” — the libretto “seemed quirkish and obscure; the first-night audience clearly did not relish a two-and-a-half-hour opera without an interval”; and the chairman of Covent Garden “leapt from his seat like a scalded cat”, The New York Times reported.21 For its part, the NYT considered it “one of the finest new operas to arrive since the war”.

The Bassarids was performed at the Deutsche Oper in Berlin, in 1966; at La Scala in 1967; at Santa Fe, USA, in 1967; and in the UK in 1974, where it was the most enthusiastically received new opera since Peter Grimes.22 It was recently staged at Salzburg in 2018 and at Berlin’s Komische Oper in 2019.

Gods and goat singing

The Bacchae tells a primal myth: according to the psychologist Erich Neumann, Dionysus belongs to the orgiastic realm of the Great-Mother and her son-lover Osiris / Adonis / Tamuz; Pentheus becomes the reluctant son-lover of his own mother, transformed into the Great-Mother.23 (Henze quotes Bach’s St. Matthew’s Passion to highlight parallels between the mythical martyrdoms of these gods and of Jesus.24)

The Bassarids, Henze believes, takes a Freudian/Jungian approach to the myth, reinterpreting the “archaic” Euripides through the lenses of Christianity and psychoanalysis25:

The basic conflict in The Bassarids is between social repression and sexual liberation: the liberation of the individual. It shows people as individuals breaking out of a social context, as a road to freedom, as the intoxicating liberation of people who suddenly discover themselves, who release the Dionysus within themselves.

Pentheus (ego) embodies the dark side of the Apollonian temperament (reason, order, structure): he is both repressive and sexually repressed, a rigid moralist who lacks self-knowledge, who thinks in categories, definitions, absolutes, and who becomes a tyrant to stamp out a new cult, killing its adherents. “The King of Thebes, a well-meaning young man, brought up by the modern philosophers of Greece, becomes the victim of his repressed sexuality” and “supresses this freedom movement, officially and within himself”.26

Dionysus (id) — god of wine, dance and pleasure, liberty and libertinism, chaos and disorder, madness, theatre — is a liberating force, but also wild, chaotic, vengeful and vindictive. He is cruel and capricious: “man-smasher, tearer, devourer of raw flesh”. He is completely amoral: “What is his goodness to me?” he says, rejecting Beroe’s plea to spare Pentheus. Indeed, “The strong gods are not good.”

Their opposition is conveyed musically: Pentheus is a baritone, he declaims rather than sings, he is associated with brassy fanfares; Dionysus is a tenor, often beguilingly lyrical, associated with strings and wind instruments. Henze’s own sympathies did not lie exclusively with one or the other: “In each person there is a Pentheus and a Dionysus.”27

The two forces come into conflict: Dionysus disrupts Pentheus’s ordered world, collapses the binary oppositions through which Pentheus sees the world — and Pentheus breaks and falls apart. It is as if the conservatives of the 1950s were confronted with the hippy movement of the 1960s: flower children dancing on hillsides, strumming guitars, and adoring their charismatic guru — and the conservatives went on a wild and mind-expanding acid-fuelled trip that turned lethal and bloody.

The opera ends with devastation: the palace of Thebes destroyed, its sole remnant a blackened wall covered in vines; the royal family shattered, son killed by mother. The curtain falls on Maenads worshipping enormous fertility idols (oldest and most primitive of religions): “Incomprehensible Mysteries, not for mortals to know. We see not, we hear not. We kneel and adore.” Unquestioning blind faith have triumphed. Dionysus has brought the rule of the élite crashing down, but he has also destroyed society.

Does such a god deserve reverence? Euripides — suspected in his time of being an atheist — demands that the audience question whether the gods are just or moral; after the scenes of horror, the final chorus seems spectacularly glib:

Gods manifest themselves in many forms,

Bring many matters to surprising ends;

The things we thought would happen do not happen;

The unexpected God makes possible:

And that is what has happened here to-day.

Euripides’s Dionysus, Vellacott suggests, is less a god than a dæmon, bestial and cruel, “hostile to the highest human values which the slow progress of man has won to distinguish him from beasts”; his demand that his “lawless and pitiless cruelty” be worshipped is an “affront […] to human dignity and sensibility”28. Agave curses the Olympian gods, and prophesies that like Uranus and Chronos, they shall be destroyed: “Sport with us while you can: one Tartarus waits for you all!” A mortal has passed judgement on the unjust gods. Or, as Auden told a press conference: “Dionysus ist ein Schwein.”29

And yet both the Apollonian and Dionysian forces are parts of the human psyche that must be reconciled, without rejecting one or taking either to extremes; that way lie destruction and madness, the dark side of Dionysus. As a modern-day worshipper of the deity explains: “What Dionysus wants is balance, a lightening of rigid and ordered souls that allows the richness of life to exist in their personal domains.” Pentheus singularly fails to do so; so too did the Darmstadt School. Henze’s own approach was to reconcile two seemingly opposed forces: tradition and innovation, lyricism and modernism, structure and freedom, the Apollonian and the Dionysian.

Recordings

Listen to:

Première (in German): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfXQUqepyAo

Kenneth Riegel (Dionysus), Andreas Schmidt (Pentheus) and Karan Armstrong (Agave), with the Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin conducted by Gerd Albrecht, Berlin, 1986. Koch Schwann Musica Mundi 314006. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uavtwpyBQmU

Sean Panikkar (Dionysus), Günter Papendell (Pentheus) and Tanja Ariane Baumgartner (Ariane), Kömische Oper Berlin, 2019, conducted by Vladimir Jurowski.

- Hans Werner Henze, Music and Politics: Collected Writings 1953–81, trans. Peter Labanyi, New York: Cornell University Press, 1982, p. 216. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 38. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, pp. 40–41. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 44. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 45. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, pp. 49–50. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 52. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 53. ↩︎

- Alex Ross, The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, Fourth Estate: 2007, p. 427. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 53. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 101. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 46. ↩︎

- Tom Service, “A guide to Hans Werner Henze’s music”, The Guardian, 30 October 2012. ↩︎

- Ross, The Rest is Noise, p. 427. ↩︎

- Gramophone Opera Good CD Guide, UK: Gramophone Publications, 1998, p. 172. ↩︎

- Philip Vellacott, trans. The Bacchae and Other Plays, Penguin Books, 1954, pp. 26 and 27. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 145. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 143. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 145. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 149. ↩︎

- Peter Heyworth, The New York Times, 24 November 1974. ↩︎

- Heyworth, New York Times. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, pp. 147–48. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, pp. 150–51. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 156. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Henze, Music and Politics, p. 147. ↩︎

- Vellacott, Bacchae, p. 28. ↩︎

- Heyworth, New York Times. ↩︎