LE COMTE ORY

- By Gioachino Rossini

- Opera in 2 acts.

- Libretto : Eugène Scribe and C.G. Delestre-Poirson, after Scribe’s 1816 vaudeville.

- First performed: Théâtre de l’Opéra (salle Le Peletier), 20 August 1828.

The story is set in Touraine, outside the castle of the counts of Formoutiers, during the Crusades, around the year 1200. Comte Ory, a young libertine, wants to seduce the Comtesse Adèle, who has sequestered herself in a château while her brother is away at the Crusades. He disguises himself first as a holy man (in Act I) and then as a pilgrimess (in Act II) – but his page Isolier, who loves Adèle, thwarts his plans.

| LE COMTE ORY, a horny young nobleman | Tenor | Adolphe Nourrit |

| LA COMTESSE Adèle de Formoutiers | Soprano | Laure Cinti-Damoreau |

| ISOLIER, the Comte’s page | Mezzo | Constance Jawureck |

| RAGONDE, Adèle’s friend | Mezzo | Augusta Mori |

| RAIMBAUD, the Comte’s sidekick | Bass | Henri-Bernard Dabadie |

| LE GOUVERNEUR, the Comte’s tutor | Bass | Nicolas Levasseur |

SETTING: Touraine, circa 1200, during the Crusades

Le comte Ory, châtelain redouté,

Après la gloire, n’aime rien que la beauté,

Et la bombance, les combats et la gaieté.

mediaeval ballad

What better way to start our journey into the world of opera than with Rossini? Rossini and Mozart were the first opera composers I fell in love with, five years before opera became an all-consuming passion. His music is life enhancing; its infectious gaiety makes you want to stand up and cheer for the sheer joy of being alive.

Le comte Ory, one of Rossini’s late operas written for Paris, is a comic masterpiece – a mixture of risky situation and indelicate suggestion, mediaeval chivalry and musical elegance.

It’s Rossini’s only French comic opera, and was one of the mainstays of the Parisian stage in the nineteenth century, last performed, for the 433rd time, at the Palais Garnier in 1884 – decades after many of the early comic operas and serious Neapolitan works had vanished. It influenced Auber, Adam, and Offenbach, the masters of lighter French opera.

Rossini recycled some of the music from his Il viaggio a Reims (1825), a pièce d’occasion for the coronation of Charles X, which he took off after three performances. The canny Rossini then used six pieces from Il viaggio for Ory. The Gran pezzo concertato a 14 voci, a bel canto ensemble showpiece for four baritones, four basses, three soprani, two tenors and a contralto, became the Act I finale, one of Rossini’s most exhilarating. (Rossini was an inveterate self-borrower; he’d used the overture to the Barber of Seville twice before!)

Highlights include:

- The Act I introduction (16 minutes) comprises a chorus (“Jouvencelles, venez vite”), a suave cavatine for Ory (“Que les destins prospères”) and a quartet with chorus where the chattering peasants spill out their woes to the saint, which builds up to the patented Rossinian crescendo.

- “Cette aventure singulière”, the allegretto of his tutor’s aria

- The duet “Ah! quel respect, Madame” (another borrowing from Viaggio) – sung here by Sumi Jo and John Aler.

- The generally acknowledged jewel of the opera is the trio “A la faveur de cette nuit obscure” (sung here by Juan Oncina, Sari Barabas and Cora Canne-Meijer in the 1956 Gui production)

Among Rossini’s comic operas, it’s closest in spirit to Matilde di Shabran, which also combines sexual politics with the romance of the Middle Ages. The tenor is, unusually, the antagonist in both operas. In Matilde, he’s a misogynist who’s tamed by a wily woman; in Ory, he’s a satryriasist with designs on the soprano. Juan Diego Flórez, the Rossinian tenor of the day, has sung both male roles opposite Annick Massis.

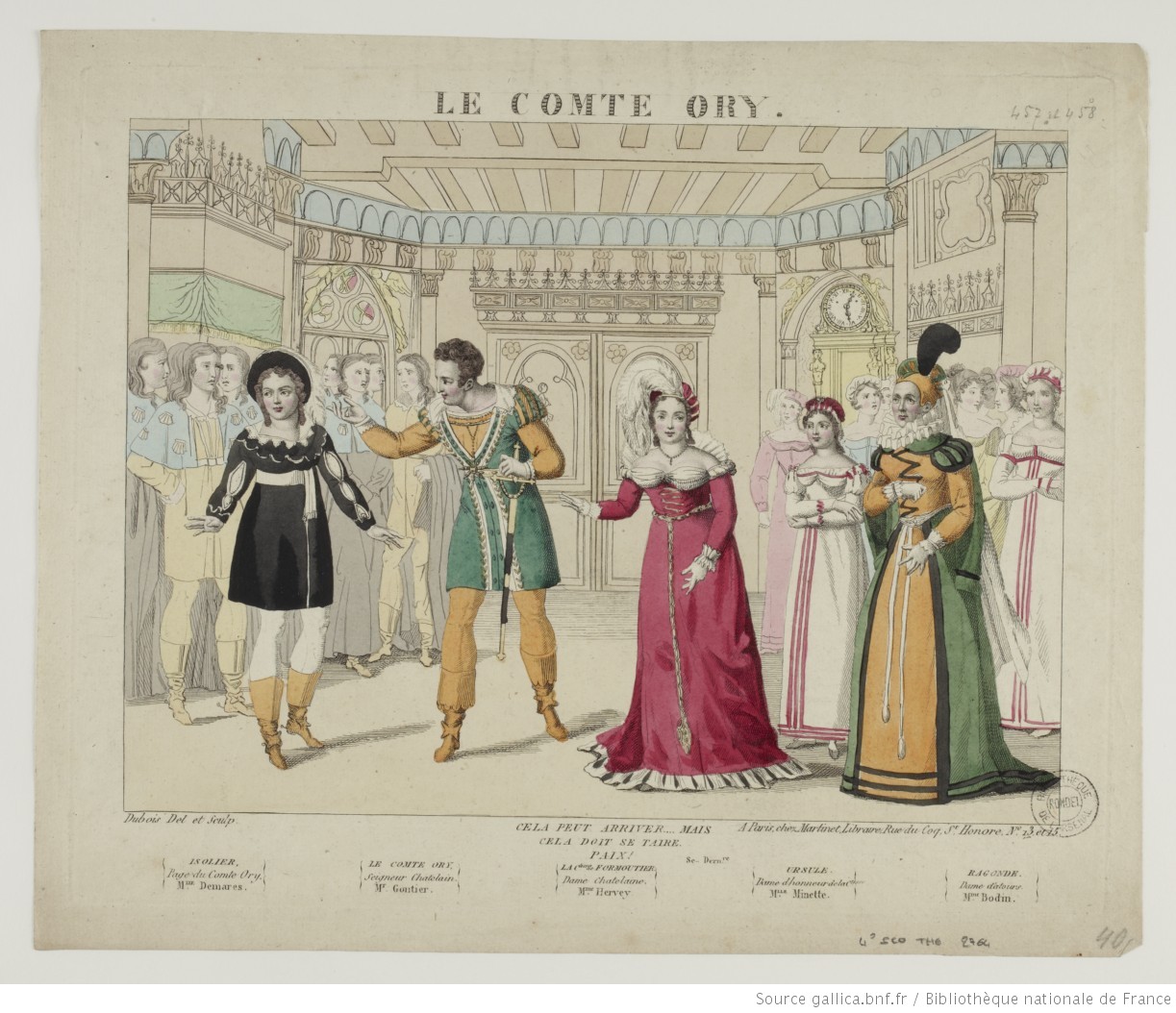

![8. [Costume];](https://operascribe.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/8-costume.jpeg?w=586)

Ory is, like Don Giovanni, a creature of pure animal appetite and impulse. He wants to seduce as many women as he can, and get drunk.

“Eating, loving, singing, and digesting,” Rossini once remarked, “are, in truth, the four acts of the comic opera known as life, and they pass like bubbles of a bottle of champagne. Whoever lets them break without having enjoyed them is a complete fool.”

Ory’s single-minded pursuit of pleasure, though, makes a fool of him. He thinks he’s cleverer than he is, the other characters call him a demon and are appalled by his wickedness – but his tutor easily rumbles his disguises and his page outwits him.

![4. [Costume];](https://operascribe.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/4-costume.jpeg?w=694)

Adèle is a restrained moralist, the super-ego to Ory’s id. She lives in a castle as tightly secured as a chastity belt, and has repressed her feelings to the point of neurosis. She is, she says towards the end of Act I, a victim of melancholy (“en proie à la tristesse”), and wants the holy man’s advice. The Comte’s remedy is simple: fall in love. Yes, she agrees, in a burst of coloratura – and declares her feelings for Isolier.

Adèle wants true love, the sincere lover who knows how to conceal his tender ardour. The Comte is never sincere; he spends nearly all the play disguised, and the only time he is himself is when he is unmasked. (Is he sincere? wonders his Tutor, when he suspects the holy man is the Comte in disguise.) Ironically, Isolier – who, as the Comte’s page, has the potential to become like his master – is both sincere and insincere. The character is sincere, a clever, high-spirited, affectionate youth, but the singer playing him is only her sex when the character is disguised.

The prolific Eugène Scribe based the libretto on a vaudeville he wrote in 1816, an “anecdote of the 11th century” based on a mediaeval ballad about the libidinous Comte Ory. (You can find the vaudeville here.)

In the original ballad, the Count and his companions assail a convent, disguised as nuns – and seduce the abbess and her sisters.

Neuf mois ensuite, vers le mois de janvier,

L’histoire ajoute comme un fait très singulier,

Que chaque nonne eut un petit chevalier.

A little knight for a night’s work! Obviously a play in which an entire convent is deflowered would never do as family entertainment.

(Three years later, though, under the July Monarchy, Scribe would create a convent of damned undead nuns for Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable, and six years after that, for Auber’s Domino noir, he would send a novice nun on one last spree before she takes her final vows and became abbess. Honour is saved; she’s released from her vows so she can marry.)

This is still a risqué opera, reveling in the sort of sophisticated naughtiness that pleased the sophisticated Parisians. Its theme is a man making an assault on a woman’s virtue, but virtue triumphs. It flirts with immorality without consummating it. The Comte wants to seduce the Comtesse, but the Comtesse resists his blandishments; the audience wants to see both the seduction (at least the attempt), and her resistance.

It riffs off the ballad’s religious mockery; the abbess becomes a mere countess, but the Comte disguises himself as a holy man to seduce the village girls; later, he and his cronies infiltrate the château disguised as pilgrims (not nuns). They raid the cellars and carouse, breaking off to sing hymns whenever their hosts go by.

There’s also a whiff of taboo sexuality. The Comte’s page Isolier is a trousers role, a male part sung by a mezzo; at the end, Isolier dresses up as Adèle – and the Comte makes love to him, believing he is she. After making love to his twice-transvestite page, he creeps out through a back passage, in disgrace and his libido dampened, while Isolier claims the girl. It’s as if Don Giovanni’s servant were Cherubino, not Leporello, and Cherubino waltzed off with Donna Elvira, with nary a statue in sight. Pants roles (principal boys) were, of course, a long tradition of opera; many of Rossini’s serious operas had armour-bearing mezzos playing men, but in an opera as risqué as this, one does wonder. Besides, a woman playing a boy disguised as a woman, made love to by a man who mistakes her for a woman, and who pairs off with another woman? We’re not so far here from Strauss’s Rosenkavalier.

SYNOPSIS

Based on Piotr Kaminski, Mille et un opéras, Paris, Fayard, 2003

- Conductor: François Antoine Habeneck

- Director: Adolphe Nourrit

- Set designs: Charles Ciceri

- Costumes: Hippolyte Lecomte.

ACT I: The courtyard before the castle of Formoutiers

No. 1 – Introduction : « Jouvencelles venez vite » (Raimbaud, Alice, Ragonde, chorus)

Cavatine : « Que les destins prospères » (Comte Ory)

Récitatif et chœur : « Je viens à vous, parlez, Dame trop respectable » (Comte Ory, Ragonde, Alice, Robert)

Quatuor et chœur : « Moi je réclame » (Comte Ory, Raimbaud, Ragonde, Alice)

Récitatif et chœur : « De grâce, encore un mot »

No. 2 – Air et chœur : « Veiller sans cesse, craindre toujours » (Gouverneur)

Récitatif : « Cet Ermite, ma belle enfant »

No. 3 – Duo : « Une dame de haut parage » (Comte Ory, Isolier)

Marche et récitatif : « Isoler dans ces lieux »

No. 4 – Air et chœur : « En proie à la tristesse » (Comtesse)

Récitatif et chœur : « C’est bien, ,je suis content »

No. 5 – Finale : « Ciel ! ô terreur ! ô peine extrême ! » (All)

The men of the county of Formoutiers, led by their castellan, brother of the Countess Adèle, have left for the crusade. The young and dissolute Comte Ory, accompanied by his faithful Raimbaud, has disguised himself as a hermit to console the lonely maidens. The scoundrel’s main objective is the young and beautiful Countess Adèle, sequestered in the château of Formoutiers with several of the most beautiful women in the neighbourhood. Her duenna, Dame Ragonde, announces her imminent visit to the Comte. The Comte appears and blesses his flock, then listens to their desires. Up pop the Gouverneur, the Comte’s tutor, and his page Isolier, whom the Comte’s father sent in search of his son. The Gouverneur has had enough of his tiresome office. Seeing an unusual gathering of pretty girls, he suspects, not without reason, that the Count isn’t far away. Isolier is all a tremble to learn that the Countess is coming, because he has a crush on her. He decides to consult the hermit. The Comte is furious to discover he has a rival, but is taken by Isolier’s plan: to insinuate himself into the castle, disguised as a pilgrimess. The Comtess arrives, hardly indifferent to the young page’s charms, yet tortured by sorrow. The hermit releases the Comtesse from her vows of eternal solitude, which she welcomes with delight. The old sage also warns Adèle against the plots of the young page, who’s only acting for his master. Suddenly, the Gouverneur recognises Raimbaud, and reveals to all the world the hermit’s true identity. In the confusion, Ragonde gives the Comtesse a message from her brother: the crusade is over, and the crusaders are only two days away from the château. Furious, the Comte decides to mount his attack the next night.

ACT II: A large room in the castle

No. 6 – Introduction : « Dans ce séjour calme et tranquille » (Comtesse, Ragonde, chorus)

Quatuor : « Noble châtelaine » (Comte Ory, Comtesse, Raimbaud, Gouverneur)

Récitatif : « Quand tomberont sur lui les vengeances divines »

No. 7 – Duo : « Ah ! quel respect Madame » (Comte Ory, Comtesse)

Récitatif : « Voici vos campagnes fidèles »

No. 8 – Chœur : « Ah ! la bonne folie »

Récitatif : « L’aventure est jolie »

No. 9 – Air et chœur : « Dans ce lieu solitaire » (Raimbaud)

No. 10 – Chœur : « Buvons, bouvons, soudain »

Récitatif et chœur ; « Elle revient, silence »

No. 11 – Trio : « A la faveur de cette nuit obscure » (Comte Ory, Comtesse, Isolier)

Récitatif : « Oh ciel ! quel est ce bruit ? »

12 – Finale : « Écoutez ces chants de victoire »

The Comtesse and her friends believe themselves secure in their château. A storm breaks, and someone knocks at the door: it’s a group of unhappy pilgrimesses, 14 of them, fleeing the outrages of both the tempest and Comte Ory. One of them comes to present her homages to the Comtesse.

Her ardent hand-kissing slightly worries the beautiful Adèle who nonetheless doesn’t suspect another trick by the Comte. The pilgrimesses are, in reality, his disguised companions. Raimbaud discovers the castle’s wine cellar, occasion for a jolly song. Isolier announces to the Comtesse and her friends that the crusaders will soon arrive. Learning of the pilgrimesses’ presence, the page immediately guesses their true identities. He must prevent at all costs the husbands from learning they were there. Under cover of darkness, the Comte tries to seduce Adèle. Disguised as a woman, Isolier responds to his advances, all the while seizing the opportunity to declare his love to the Comtesse.

No longer able to contain himself, the Comte drops his disguise and showers the page with tender kisses. We hear the bugle; it’s the crusaders, among them the Comtesse’s brother and the Comte’s father. The Comte and his companions flee through a secret passage.

PERFORMANCES

To watch: The 1997 Glyndebourne recording (on YouTube). It has an excellent, largely Francophone cast (Marc Laho, Annick Massis, Ludovic Tézier), while Diana Montague is a very sympathetic Isolier. It’s staged straight (no bizarre or alienating “concepts”) but imaginatively, and is very funny.

The 2011 Met broadcast has a starrier cast – Flórez, Diana Damrau and Joyce DiDonato – but I’m not fond of Bartlett Sher’s “stage within a stage” concept.

To listen to: Vittorio Gui’s 1956 recording, starring Juan Oncina, Sari Barabas and Cora Canne-Meijer; some cuts, but full of Gallic wit. Gramophone said, “like champagne and the works of P.G. Wodehouse, one of life’s few infallible tonics”.

Next time: Matricide and human sacrifice.

CRITICISM

Félix Clément, Dictionnaire des opéras, 1869

Source: http://artlyriquefr.fr/dicos/operas%20-%20C.html

« Le livret était un nouvel arrangement d’une pièce que Scribe et Poirson avaient donnée au théâtre du Vaudeville en 1816. La musique avait été en grande partie composée pour un opéra de circonstance en l’honneur du sacre de Charles X, et intitulé Il Viaggio a Reims. Cet ouvrage, représenté à l’Opéra italien pendant l’été de 1825, avait eu pour interprètes Mmes Pasta, Cinti-Damoreau et MM. Bordogni, Pellegrini et Levasseur. Quoi qu’il en soit, et malgré les remaniements auxquels le livret et la partition durent être soumis, le Comte Ory passe, avec raison, pour un des meilleurs opéras de Rossini. Parmi les morceaux composés expressément pour l’opéra français, nous mentionnerons le bel air de basse Veiller sans cesse, dont l’accompagnement est rythmé d’une manière neuve et piquante ; le chœur des chevaliers, Ah ! la bonne folie ; le chœur des buveurs, qui est un chef-d’œuvre, Qu’il avait de bon vin, le seigneur châtelain, et le trio : A la faveur de cette nuit obscure. Tout le reste de l’ouvrage offre de ravissantes mélodies. La cavatine du premier acte, Que les destins prospères, est d’une facture tout italienne de la première manière du compositeur. La prière, Noble châtelaine, est d’une harmonie et d’un rythme délicieux. Nulle part, peut-être, le compositeur n’a fait preuve de plus d’esprit, ni obtenu des effets plus variés que dans l’instrumentation du Comte Ory. Adolphe Nourrit, Mme Damoreau et Levasseur ont été les interprètes les plus applaudis de cette riche partition. »

Translation

The libretto was a new arrangement of a piece that Scribe and Poirson gave at the théâtre du Vadueville in 1816. The music was in large part composed for an occasional opera in honour of Charles X’s coronation, entitled Il Viaggio a Reims. That work, performed at the Opéra italien in the summer of 1825, featured Mmes Pasta, Cinti-Damoreau and MM. Bordogni, Pellegrini and Levasseur. Be that as it may, and in spite of the necessary rearrangements to the libretto and the score, le Comte Ory rightly passes for one of Rossini’s best operas. Among the pieces expressly composed for the French opera, we will mention the beautiful bass aria Veiller sans cesse, whose accompaniment is rhythmic in a new and pungent way; the knights’ chorus, Ah! la bonne folie; the drinkers’ chorus, Qu’il avait de bon vin, le seigneur châtelain, which is a masterpiece; and the trio: A la faveur de cette nuit obscure. All the rest of this work offers delightful melodies. The cavatina in the first act, Que les destins prospères, is entirely Italian, in the composer’s first manner. The prayer, Noble châtelaine, is of a delicious harmony and rhythm. Nowhere, perhaps, has the composer shown more wit, or varied his efforts more than in the instrumentation of the Comte Ory. Adolphe Nourrit, Mme Damoreau and Levasseur were the most applauded interpreters of this rich score.

Hector Berlioz, Feuilleton du Journal des Débats (28 May 1839)

Source: http://www.hberlioz.com/feuilletons/debats390528.htm

Le Comte Ory est bien certainement l’une des meilleures partitions de Rossini ; jamais peut-être, dans aucune autre, le Barbier seul excepté, il n’a donné carrière aussi librement à sa verve brillante et à son esprit railleur. Le nombre des passages faibles, ou tout au moins criticables sous certian rapports, que contient cet opéra, est réellement très petit, surtout en comparaison de la multitude de morceaux charmans qu’on y peut compter. L’introduction instrumentale qui sert d’ouverture est en général d’un style singulier, ou pour mieux dire, grotesque, qui pourrait la faire considérer toute entière comme une espèce de farce musicale, sans le thème du vaudeville du Comte Ory que l’auteur y a intercalé et ramené plusieurs fois avec autant d’adresse que d’éclat. On ne voit guère en effet à quoi se rapportent ces gémissemens, ces miaulemens de violoncelle, se ralentissant et s’affaiblissant peu à peu comme un râle de mourant. Ce ne peut être qu’une boutade de l’auteur disposé, le jour où il l’écrivit, à rire un peu de son art et du public. A part ce caprice d’un instant, le reste de l’ouvrage a été évidemment composé avec amour ; on remarque partout un luxe de mélodies heureuses, de dessins nouveaux, d’accompagnemens, d’harmonies recherchées, de piquans effets d’orchestre, et d’intentions dramatiques aussi pleines de raison que d’esprit. On pourrait dire seulement à propos de la vérité d’expression, qu’elle manque dans la premier air : Que les destins prospères. Cette cavatine gracieuse, semée de traits rapides, de vocalisations légères, contraste évidemment avec le costume monacal revêtu par le comte Ory. Puisque le jeune étourdi a couvert sa tète d’un noir capuchon et son menton d’une longue barbe grise, puisqu’il a pris les allures pesantes, la démarche cassée d’un vieil ermite, il devait aussi, ce me semble, déguiser sa voix et le caractère de son chant. On découvre bien aussi par-ci par-là des fautes de prosodie et des interruptions choquantes dans des paroles qui ne peuvent en aucun cas être scindées de la sorte, comme celles du final du premier acte, par exemple, où le comte arrête le premier membre de sa phrase sur les mots : Et du destin, se tait pendant trois ou quatre mesures, et reprend, pour finir sa période par ceux-ci : Braver les coups. La faute n’en est pas sans doute au compositeur ; on sait que ce morceau et beaucoup d’autres du même ouvrage furent écrits sur un livret italien, Il Viaggio a Reims ; c’est donc au traducteur qu’il faut s’en prendre. En tout cas, le musicien aurait dû surveiller son travail, et ne pas lui permettre de prendre d’aussi grandes libertés. Mais que de compensations à ces taches légères ! que de richesses musicales dans ces deux actes ! Le duo entre le page Isolier et l’ermite, l’air du gouverneur, le morceau d’ensemble sans accompagnement, magnifique andante d’une symphonie vocale, la stretta du final, Venez, amis, et au second acte, le chœur des femmes, Dans ce séjour ; la prière, Noble châtelaine si habilement mêlée au bruit de l’orage, l’orgie, le duo, J’entends d’ici le bruit des armes, dont le motif principal a tant d’ampleur et d’élan ; et enfin ce trio merveilleux, A la faveur de cette nuit obscure, le chef-d’œuvre de Rossini, à mon sens, forment une réunion de beautés diverses qui, adroitement réparties, suffiraient au succès de deux ou trois opéras. Cependant, et je n’ai probablement pas besoin de le dire, la fameuse cadence finale italienne qui se trouve trente ou quarante fois reproduite dans les deux actes du Comte Ory, n’en est pas moins plus que jamais une des choses les plus faites pour impatienter un auditeur attentif. O la sotte, ô l’insipide formule ! quand donc en serons-nous délivrés ? Beaucoup de gens en rient ; cela m’arrive aussi quelquefois ; mais il faut, en ce cas, que je sois de bien bonne humeur.

Translation

Le Comte Ory is certainly one of Rossini’s best scores. Never, perhaps, in any other opera except the Barber, has he given so free a rein to his brilliant verve and his mocking wit. This opera contains very few feeble, or at least criticable, passages, especially compared to the multitude of charming pieces. The instrumental introduction, which serves as an opening, is generally singular, or rather grotesque; if it were not that the author introduced and brought back several times the theme of Comte Ory with as much skill and brilliance, one would think of it as a sort of musical farce. One hardly sees what these shudderings and mewings from the violincello, slowing and weakening like a dying man’s last breaths, mean. It can only be a joke on the part of the author who, on the day that he wrote it, laughed a little at his art and his public. Apart from this momentary caprice, the rest of the work was obviously composed with love. Everywhere there is a luxury of happy melodies, new designs, accompaniments, sought-after harmonies, piquant orchestral effects, and dramatic intentions as full of reason as wit. All one can say about truthful expression is that it’s missing from the first aria: “Que les destins prospères”. This graceful cavatina, swiftly moving and lightly vocalised, obviously contrasts with the monk’s costume worn by Count Ory. Since the harum-scarum young man has covered his head with a black hood and his chin with a long grey beard, because he pretends to walk heavily, in the broken gait of an old hermit, he should also, it seems to me, disguise his voice and his style of singing. Here and there, too, we find prosodic errors and shocking interruptions in words which cannot be split up, as in the finale of the first act, where the Count stops the first part of his phrase on the words: “Et du destin”, is silent for three or four measures, and then continues, to finish his phrase with the words “Braver les coups”. The fault is certainly not the composer’s. We know that this number and others in the work were written on an Italian libretto, Il Viaggio a Reims; the translator is to blame. In any case, the musician should have watched his work, and not allowed him to take such liberties. But what compensations for these blotches! What musical riches in these two acts! The duet between the page Isolier and the hermit, the tutor’s aria, the unaccompanied ensemble, magnificent andante from a vocal symphony, the finale’s stretta Venez, amis, and in the second act, the women’s chorus, Dans ce séjour; the prayer, Noble châtelaine so skillfully mingled with the noise of the storm, the orgy, the duet, J’entends d’ici le bruit des armes, with its big, energetic principal theme; and finally that marvelous trio, A la faveur de cette nuit obscure, in my opinion, Rossini’s masterpiece. These form a collection of diverse beauties which, adroitly distributed, would suffice for the success of two or three operas. Nevertheless, and I probably don’t need to say it, the famous Italian final cadence, which is reproduced thirty or forty times in the two acts of Comte Ory, is more than ever one of the most accomplished things to madden an attentive listener. O the stupid, insipid formula! When shall we be delivered from it? Many people laugh at it; I do too, sometimes; but in that case I must be in a good mood.

One of my favorite operas!

That trio… 💖

What are your thoughts on the 2003 Rossini Festival recording with JDF? 😍

LikeLike

That was my very first review! I haven’t heard the 2003 recording, actually. I saw Florez in the Met production (the one with the onstage wind? machine and rolling around in the bed at the end). My recording is the 1957 Gui, with Juan Oncina. Probably long since superseded!

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I started to look at what Opera is both you and Phil were reviewing, I was both overwhelmed and extremely excited at the same time. I didn’t know where to start, so I just was jumping around looking at different ones, than I thought, I wonder what his first review was. So when I saw it was this one, it put a big smile on my face. But I’m alsolooking forward to reading both of your reviews on uppers that either I’ve heard of but have never listened to as well as the rare ones that I have never heard of.

I lived in New York City for 15 years, so I was able to see many operas. There were some productions that I wanted to see but I was not able to, including the Ory you mentioned. I have seen the video though.

Even though I love the recording with Florez, as you know it always comes down to one’s personal taste.

Many operas with multiple recordings often have as the “considered to be the best” recording with singers whose voices I struggle to enjoy such as a… uh… Particular singer who, although I admire very much, I simply can’t listen to on account of it causing my skull to begin cracking and separating at the cranial sutures much like a fault line during an earthquake. 😉

LikeLike

*first sentence “opera is” s/b “operas”

LikeLike