LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN

- By Jacques Offenbach

- Opéra in a prologue, 3 acts, and an epilogue

- Libretto: Jules Barbier, after Barbier and Michel Carré’s play Les Contes d’Hoffmann (1851), based on Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann’s “Der Sandmann” (“The Sandman”), “Rath Krespel” (“Councillor Krespel” / “The Cremona Violin”), and “Das verlorene Spiegelbild” (“The Lost Reflection”).

- First performed (without the Venice act): Opéra-Comique (2e salle Favart), Paris, 10 February 1881. Director: Léon Carvalho. Sets: Antoine Lavastre. Costumes: Théophile Thomas. Condutor: Jules Danbé.

- First complete performance: Opéra-Comique (2e salle Favart), Paris, 13 November 1911

| HOFFMANN, poet | Tenor | Jean-Alexandre Talazac |

| OLYMPIA, mechanical doll ANTONIA, young woman GIULIETTA, courtesan STELLA, opera singer | Soprano | Adèle Isaac |

| CONSEILLER LINDORF COPPÉLIUS, optician DR. MIRACLE CAPTAIN DAPERTUTTO | Bass-baritone | Émile-Alexandre Taskin |

| NICKLAUSSE | Mezzo | Marguerite Ugalde |

| The MUSE | Mezzo | Mole-Truffier |

| ANDRÈS, Stella’s servant COCHENILLE, Spalanzini’s servant FRANTZ, Crespel’s servant PITTICHINACCIO, Giulietta’s fool | Buffo-tenor Tenor | Pierre Grivot |

| NATHANAËL, student | Tenor | Chenevières |

| HERMANN, student | Baritone | Teste |

| WILHELM, student | Bass-baritone | Colin |

| WOLFRAM, a student | Tenor | Piccaluga |

| LUTHER, innkeeper | Bass | Étienne Troy |

| SPALANZINI, inventor | Tenor | E. Gourdon |

| CRESPEL, Antonia’s father | Bass | Hippolyte Belhomme |

| Voice from the tomb, Antonia’s mother | Mezzo | Mme Dupuis |

| PETER SCHLÉMIL, Giulietta’s lover | Baritone | |

| Students, Guests | Chorus |

SETTING: Nuremberg; Paris; Munich; Venice.

Offenbach’s last opera. There is no fixed score, and various versions exist, as Offenbach died before he could complete the work. The Venice (Giulietta) act, for instance, wasn’t performed at the première, and the Antonia act was moved from Munich to Venice so they could use the famous Barcarolle. Two of the finest pieces in the score – the aria “Scintille, diamant” and the Septet – weren’t composed for the opera.

Offenbach’s last work is astonishing. It’s an opera of ideas rather than of feeling; it comments on the nature of opera and the creative artist’s imagination, while blending science fiction and fantasy with comedy.

And it features a drunken poet, a robot, mad scientists (one with a collection of eyeballs), a singing painting, a courtesan and a dwarf out of a Weimar cabaret, four devils, and the artist’s Muse.

Heady stuff for the 1880s.

Hoffmann is the protagonist of his own opera. The conceit is that he tells his drinking cronies the stories of three women he loved: Olympia (in Paris), really an automaton; Giulietta (in Venice), who stole his reflection; and Antonia (in Munich), who sang herself to death.

He reveals at the end that all three women – the wind-up doll who sings mechanical coloratura, the heartless courtesan who fakes emotion, and the consumptive soprano who surrenders her life to her desire for fame and glory – are the same woman: the opera singer Stella.

The three heroines are (as the Seattle Opera Blog suggests) embodiments of opera:

- Olympia, in the comic Paris act, is French coquetterie, a doll who’s trotted out to display her accomplishments for her wealthy admirers, just as many singers and ballerinas eked out their earnings by genteel prostitution;

- The decadent Venetian courtesan Giulietta is Italian vocal virtuosity and faked emotion. Significantly, she has no aria of her own, but only sings in duets. If an aria is an expression of interiority, she has no self to express; she counterfeits emotion, and can only do so in duets or ensembles.

- Antonia is the star singer’s ego. The villain appeals to her vanity, and makes her destroy herself by luring her into singing an Italianate cabaletta, a crowd-pleasing aria that shows off the soprano’s high notes.

Offenbach parodied grand opera – particularly Meyerbeer and Rossini – in his opéras bouffes. Here, in a full-blown opera, he condemns opera itself as empty spectacle catering to singers’ vanity.

Hoffmann, like Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini and Wagner’s Meistersinger, is also about the creative artist. Berlioz and Wagner show the revolutionary Romantic genius triumphing over his bourgeois critics / rivals in love and getting the girl. Hoffmann – dreamer, poet, and idealist – is unsuccessful in love; his art is his consolation.

His Muse, disguised as his friend Nicklausse, accompanies him on his adventures. She is ambiguous, even sinister; she blocks Hoffmann, and even helps the Enemy (the villain in each episode, all played by the same baritone) thwart his efforts to find true love. She needs Hoffmann to suffer to create stories.

(Is artistic inspiration a parasite?)

Hoffmann takes events, the raw material of truth, and turns them into literature. Those stories are fictionalized versions – not memories – of what happened. The bulk of the action – three whole acts – doesn’t take place. (I can only think of one near-contemporary opera with a similar idea: Saint-Saëns’s Timbre d’argent, also by Barbier and Carré.)

This is sophisticated stuff, and anticipates twentieth century literature: an unreliable narrator and a narrative that calls attention to its own fictionality and critiques its form.

It is only a small step from Hoffmann to the absurdist, Modernist operas of the twentieth-century – to Strauss, Korngold, Weill, and Hindemith.

Synopsis

Synopsis based on G. Schirmer, New York, c. 1911, and Piotr Kaminski, Mille et un opéras, Fayard, Paris, 2003

PROLOGUE

Hoffmann is a young poet who has been unfortunate in his love-affairs; and the stories of these affairs, which are acted in detail, form the body of the opera.

The Muse awaits her protégé, the poet Hoffmann, whose fate will be decided this evening. She has a rival, the opera singer Stella, appearing in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. The Muse takes on the form of Hoffmann’s loyal friend Nicklausse. The battle for Hoffmann’s soul also involves another: the rich and powerful councillor Lindorf, determined to snatch the singer from the lovestruck poet.

The first act of Don Giovanni has just finished, and Hoffmann and his friends hit the bar. In spite of the merry drinking-songs and the light-heartedness of his companions, Hoffmann is melancholy. He is accused of being in love and for a while succeeds in assuming a forced cheerfulness, answering the gibes of his friends with a jolly little song describing an amusing dwarf named Kleinzach. But he soon wanders into an incoherent recital of the charms of a mysterious lady, and on being further rallied and questioned by his comrades he agrees to tell them the tales of his three luckless love-affairs.

ACT I: Paris

The first act shows the magnificent home of the learned Dr. Spalanzani, who tells his pupil, Hoffmann, of the beauty of his “daughter” Olympia. Hoffmann is enchanted with the girl at his first distant view of her and does not realize that she is only a mechanical doll, the invention of Spalanzani and a certain Dr. Coppelius. The latter soon enters, and succeeds in selling Hoffmann a pair of magic eye-glasses which have the effect of making Olympia appear to the wearer as a real human being. Spalanzani, who is in financial straits, hopes to retrieve his fortunes through the wonderful automaton and accordingly buys from Coppelius the complete rights to the invention, paying him with a draft which he knows will not be honored. After the departure of Coppelius, Spalanzani entertains a large company of guests to whom he proudly exhibits the marvellous Olympia.

Hoffmann falls even more deeply in love with her after he has heard her sing. Left alone with her for a few moments he declares his passion and, meeting with no response, dances with her. She whirls him around until he is exhausted, running into the other dancers and causing general confusion and laughter. Spalanzani finally succeeds in stopping the mechanism which Hoffmann had unconsciously started, and has the doll removed from the room. Coppelius enters suddenly, in a fury at having been cheated by Spalanzani, and rushes into the corridor ; a crashing sound is heard and in a moment the guests realize that Coppelius has taken vengeance by smashing the automaton in pieces. Hoffmann is overcome with horror and chagrin, and as the guests make merry at his expense the curtain falls.

ACT II: Munich

Hoffmann is in love with Antonia, the daughter of Crespel, a musician. She suffers from a malignant fever which will prove fatal if she over-exerts herself with singing. Her father has forbidden her to use her voice, but she still permits herself an occasional song in the company of Hoffman, who is unaware of her danger. The malignant Dr. Miracle,

who pretends to be a physician but is in reality a fiend with hypnotic powers, is supposedly restoring Antonia to health. In reality he intends to kill her as he killed her mother. When Hoffmann learns the truth he also forbids Antonia to sing, but Dr. Miracle now has her in his power and uses all his wiles to accomplish his villainous purpose. Finding Antonia alone he persuades her that her dead mother desires her to sing. He even conjures up a voice which Antonia believes to be that of her mother, and then tempts her further with the magic strains of his violin. Antonia’s defense is finally broken down ; she yields to the temptation and sings herself to death. Crespel and Hoffmann enter just in time to hear her last words. The frenzied father accuses the young man of the murder of his child, while Dr. Miracle gloats over the success of his plot.

ACT III: Venice

Giulietta, a famous beauty, is holding court on the banks of the Grand Canal, and Hoffmann is introduced to her by his friend Nickiausse, who, however, warns him against her charms.

After two romantic failures, Hoffmann is resigned to a debauched love affair with the courtesan. He meets some of his predecessors, including Schlemil, whom Giulietta treats with a mocking contempt. Hoffmann is deaf to Nickalusse’s good advice, and underestimates the power of Giulietta’s protector, the mysterious conjurer, Dapertutto. Through Giulietta, he has obtained Schlemil’s shadow, and now asks her for Hoffmann’s reflection.

Schlemil, who has discovered his condition, challenges Hoffmann at a casino.

In a passionate love-scene he begs her to fly with him and leave Schlemil forever. Giulietta is piqued at his former coldness and determines to play a trick on him. She tells him that he must procure the key of her room from Schlemil, after which she will join him in flight. Hoffmann obtains the key by killing Schlemil in a duel, and she manipulates him into offering her his reflection. Giulietta departs in a gondola with another lover, a misshapen and dwarf-like creature known as Pittichinaccio. The police come to arrest Hoffmann. Dappertutto offers him a mirror; he has no reflection. Unable to bear Giulietta’s mocking laugh, he tries to stab her, but it’s Piticchinaccio who receives the blow. Giulietta falls on his body, distraught.

EPILOGUE: Luther’s inn

Back to the inn, where Hoffmann has just finished telling the third history. Lindorf is delighted to see the drunken and depressed state into which Hoffmann has fallen; the poet won’t be able to claim Stella. Nicklausse tells the moral of the story: Olympia, Antonia, and Giulietta were all three facets of the same woman, the singer Stella. The Muse celebrates the death of the lover and the birth of the poet.

Recordings

Oeser edition: Neil Shicoff (Hoffmann), Luciana Serra (Olympia), Jessye Norman (Giulietta), Rosalind Plowright (Antonia), José van Dam (Villains), Ann Murray (Nicklausse/the Muse), conducted by Sylvain Cambreling, Brussels Opéra National du Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, EMI 1988

Kaye-Keck edition: Roberto Alagna (Hoffmann), Natalie Dessay (Olympia), Sumi Jo (Giulietta), Leontina Vaduva (Antonia), José van Dam (Villains), Catherine Dubosc (Nicklausse), conducted by Kent Nagano, Opéra National de Lyon, Erato 1996

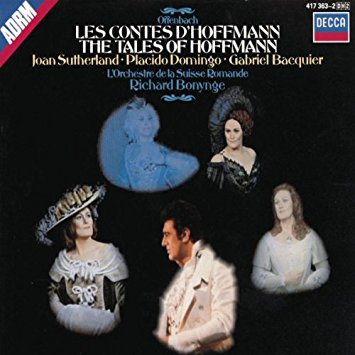

Inauthentic, but well sung: Plácido Domingo (Hoffmann), Joan Sutherland (Heroines), Gabriel Bacquier (Villains), Huguette Tourangeau (Nicklausse), conducted by Richard Bonynge, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Decca 1971

DVD: Neil Shicoff (Hoffmann), Gwendolyn Bradley (Olympia), Tatiana Troyanos (Giulietta), Roberta Alexander (Antonia), James Morris (Villains), conducted by Charles Dutoit, Metropolitan Opera of New York 1988.

Imaginative performance, using a traditional score. Watch it online at the Met’s website.

3 thoughts on “17. Les contes d’Hoffmann (Jacques Offenbach)”