- Opéra-comique in 2 acts

- Music and libretto by Hector Berlioz, after Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing

- First performed: Theater Baden-Baden, Germany, 9 August 1862

| BÉATRICE, Léonato’s niece | Mezzo | Anne Charton-Demeur |

| HÉRO, Léonato’s daughter | Soprano | Mlle Monrose |

| URSULE, Héro’s maid in waiting | Soprano | Mme Geoffroy |

| BÉNÉDICT, Sicilian officer, Claudio’s friend | Tenor | Achille-Félix Montaubry |

| CLAUDIO, Don Pedro’s aide de campe | Baritone | Jules Lefort |

| DON PÉDRO, Sicilian général | Bass | Mathieu-Émile Balanqué |

| SOMARONE, chapelmaster | Bass | Victor Prilleux |

| LÉONATO, governor of Messina | Spoken | Guerrin |

| A scribe | Spoken | |

| A messenger | Spoken | Phillipe Mutée |

| Two servants | ||

| People | Chorus |

SETTING: Messina, 16th century

Commentary

Shakespeare’s comedy about a merry war of wits mixes high comedy with pathos. Hero and Claudio, about to marry, plot to bring the sparring Beatrice and Benedick together, while the bastard Don John mutters darkly in the background and convinces Claudio that Hero has betrayed him the night before the wedding. Claudio accuses Hero at the altar, she collapses and seems to die, and Beatrice demands that Benedick kill Claudio.

Berlioz keeps only the Béatrice et Bénédict love story, dropping the Ado of Don John’s scheme against Hero. His opera is a light work, but not “nothing”. For melodic invention, beauty and warmth, this “caprice written with the point of a needle” is Mozartean.

There was a star danced, and under that was Béatrice born.

The idea for adapting Shakespeare’s comedy first came to Berlioz in the 1830s, thirty years before he was commissioned to write an opera for the opening of the Theater Baden-Baden.

Berlioz was old, sick and disappointed when he composed Béatrice; none of his operas had been successful, and the Paris Opéra refused to mount Les Troyens, his historical epic based on Virgil. With Béatrice, he could lose himself in his beloved Shakespeare, “the supreme creator, after the Almighty”.

“I’m really enjoying myself and composing the score con furia,” he told the German composer Peter Cornelius. “It’s gay, caustic, occasionally poetic; it brings a smile to the eye and to the lips.”

The opera may also be his artistic testament – and a rebuttal to the Wagnerian movement.

At a time when the musical avant-garde saw Wagner as the future, Berlioz’s last opera is almost deliberately old-fashioned in its emphasis on music over drama.

Critics of the time lumped Berlioz with Wagner as a musician of the future. Berlioz rejected the idea. “Wagner,” he thought, “is obviously mad.” The music of the future, with its “endless melody” and independence from form, went against his aesthetic principles; it was “the school of mayhem” (l’école du charivari).

“The hardest task,” he wrote while composing the Troyens, “is to find the musical form, this form without which music does not exist, or is only the craven servant of speech. That is Wagner’s crime; he would like to dethrone music and reduce it to ‘expressive accents’, exaggerating the system of Gluck, who, fortunately, did not succeed in carrying out his ungodly theory.

“I am in favour of the kind of music you call free. Yes, free and proud and sovereign and triumphant, I want it to grasp and assimilate everything, and have no Alps nor Pyrenees to block its way; but to make conquests music must fight in person, and not merely by its lieutenants; I should like music if possible to have free verses ranged in battle order, but it must itself lead the attack like Napoleon, it must march in the front rank of the phalanx like Alexander.”

He set out his views in an article in the Journal des Débats:

If the Futurists tell us: “One must do the opposite of what the rules prescribe; we are tired of melody, tired of melodic patterns, tired of arias, duets, trios and movements whose themes are developed regularly; we are surfeited with consonant harmonies, with simple dissonances prepared and resolved, with natural modulations skillfully contrived; one must take account only of the idea and forget about sensation; one must scorn the ear, strumpet that it is, one must brutalize it in order to master it; it is not the purpose of music to be pleasing to it; music must be made accustomed to anything and everything, to strings of ascending and descending diminished sevenths which resemble a knot of hissing serpents writhing and tearing each other, to triple dissonances which are neither prepared nor resolved, to inner parts forcibly combined without agreeing harmonically or rhythmically and rasping painfully against one another, to ugly modulations entering in one part of the orchestra before the previous key has made its exit; one should show no regard to the art of singing and give no thought to its nature or its requirements; in opera one must confine oneself to setting down the declamation, even if it means writing intervals that are outlandish, nasty and unsingable…

The witches in Macbeth are right: “Fair is foul and foul is fair.” If that is the new religion, I am very far from professing it; I have never been part of it, I am not now and I never shall be. I raise my hand and swear Non credo. On the contrary, I firmly believe that fair is not foul and foul is not fair. Certainly, it is not music’s sole purpose to be pleasing to the ear. But music’s purpose is a thousand times less to be unpleasing to it, to torture and destroy it.

Béatrice celebrates musical form, “free and proud and sovereign and triumphant”. All the traditional numbers of a French opéra comique are there, but Berlioz shows what they can become in the hands of a genius. There are multi-section arias (complete with coloratura runs), duets and trios, with regularly developed themes. There are “improvised” drinking choruses accompanied by guitars and trumpets, choruses sung from the wings, and an almost eighteenth century Marche nuptiale.

Berlioz emphasises the the art of singing, particularly in the exquisite Nocturne, a duet for soprano and contralto that is one of Berlioz’s loveliest pieces. The melody slowly unfurls, and the women’s voices wrap around each other in “harmonies infinies”.

Berlioz also pokes fun at bêtises in French music, through the character of the music master Somarone (“ass”), his own addition to Shakespeare’s play. He takes to task trite rhyming (“gloire et victoire, guerriers et lauriers”) and academic fugues (also parodied in La damnation de Faust).

Little fear of Berlioz writing something trite or academic. “I think it is one of the most spirited and original [works] I ever wrote,” he wrote. It may not be as rich as Cellini, as colourful and kaleidoscopic as Faust, as epic as Les Troyens, but this little work can hold its own among those masterpieces.

Synopsis

Based on Piotr Kaminski, Mille et un opéras, Fayard, Paris, 2003

ACT I: In Léonato’s park

After their victory over the Moors, the Sicilian army returns to Messina. Léonato’s household celebrates the arrival of Don Pédro and his young friends Claudio and Bénédict, the first in love with and loved by Héro, Léonato’s daughter, and the other waging a merry war of wits with his niece Béatrice. Héro sings of her joy at seeing Claudio again.

Béatrice and Bénédict start duelling immediately. Don Pédro having obtained Léonato’s agreement for Héro and CLaudio’s marriage, Bénédict rails against the institution of marriage, swearing never to succumb, which amuses his friends.

Somarone, conductor of Léonato’s choirs, has prepared a vocal masterpiece for the party. Convinced that Béatrice and Bénédict are madly in love, Don Pédro, Léonato, and Claudio hatch a plot to unite them. Knowing themselves overheard by Bénédict, they talk loudly of Béatrice’s passion for him. That’s enough for Bénédict. Héro and her friend Ursula, already plotting against Béatrice, admire the charms of the night.

ACT II: A large room in the governor’s mansion

Somarone and the servants celebrate the treasures of Léonato’s wine cellar. Béatrice, victim of the plot, thinks Bénédict mad with love, and realises she is attracted too.

Héro and Ursule find her in a state of extreme agitation, which they turn to their profit by speaking of the happiness of love.

The marriage approaches. In the garden, Béatrice and Bénédict meet awkwardly, but don’t yet declare their love. Héro and Claudio sign the marriage contract, but the clerk announces there is a second contract prepared – and Béatrice and Bénédict sign it.

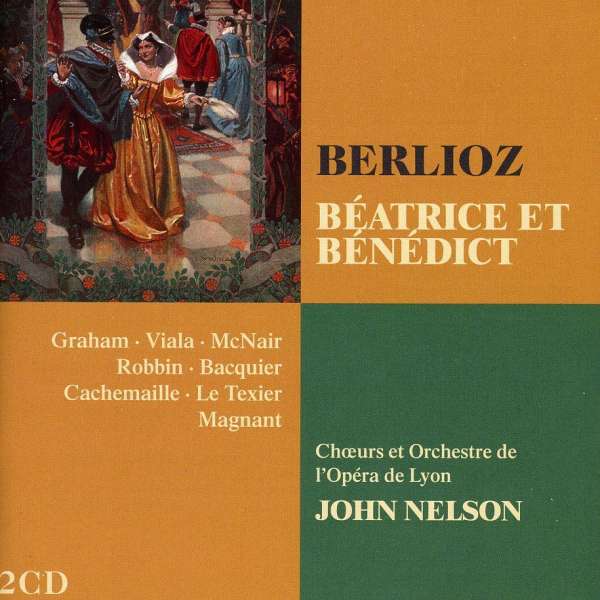

Recordings

2 thoughts on “24. Béatrice et Bénédict (Hector Berlioz)”