- Chamber opera in 1 act

- Composer & librettist: Gustav Holst

- First performed: Wellington Hall, London, 5 December 1916 (amateur performance)

- First professional performance: Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, London, 23 June 1921, conducted by Arthur Bliss

| SĀVITRI | Soprano | Dorothy Silk |

| SATYAVĀN, her husband | Tenor | Steuart Wilson |

| DEATH | Bass | Clive Carey |

SETTING: Ancient India

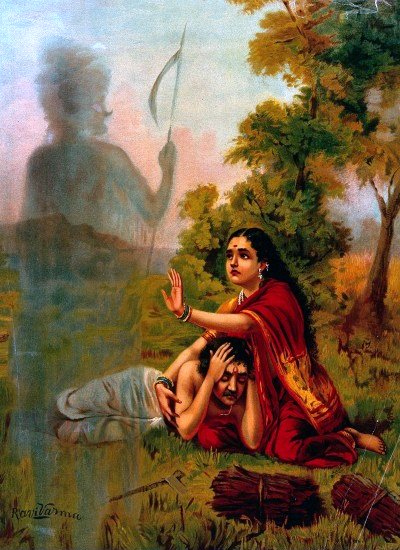

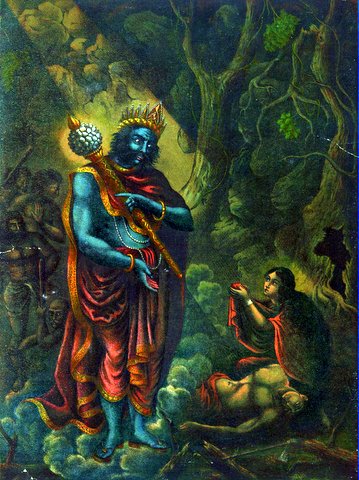

Sāvitri is the story of the loyal wife who tricks death to save her husband’s life. [1]

The story is based on an episode from the Mahabharata, the Sanskrit equivalent of the Iliad.

[1] See also Euripides’ Alcestis (the model for Gluck’s opera), and – with an unhappier ending – Orpheus and Eurydice.

Every year, at the festival of Savitri Brata (Vat Purnima in the west), Indian wives fast to pray for long life and health for their husbands.

I first came across the legend in Madhur Jaffrey’s Seasons of Splendour, Indian folktales and myths retold for children.

Yama (Death) comes to claim the soul of the woodman Satyāvan. Sāvitri charms Death into granting any boon – except sparing her husband.

“Give me life,” Sāvitri answers. “Life is all I ask of thee. ‘Tis a song I fain would be singing. Thy song, O Death, is a murmur of rest, Mine should be of the joy of striving. Where disease hath spread her mantle, Where defeat and despair are reigning, There shall my song , like a trumpet in battle resound and triumph.

“Life is a path I would travel Wherein flowers should spring up around me, Stalwart sons whom I would send where fighting is fiercest. Bright-eyed daughters following my path, Carrying life on thro’ the ages.”

Death grants her this boon.

“He giveth me life,” Sāvitri rejoices, “The life of woman, of wife, of mother, So hath he granted that which alone fulfils his word. If Satyāvan die, my voice is mute, my feet may never travel the path. Then I were but a dream, an image, floating on the waters of memory. Satyāvan only can teach me the song, can open the gate to my path of flowers – The path of a woman’s life.”

Satyāvan is restored to life. “Without thee,” Sāvitri tells him, “I am as the dead, A word without meaning, Fire without warmth, a starless night. Thou makest me real. Thou givest me life.”

Indian religion and literature fascinated Gustav Holst. Finding Victorian translations inadequate, he studied Sanskrit at University College, London, from 1909, and translated portions of the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and the poems of Kālidāsa.

Many of these became the basis for music: the three-act opera Sita (1899-1906); the symphonic poem Indra (1903); hymns from the Rig Veda, the Hindu scriptures (1908-14); and Two Eastern Pictures (1909-10) and The Cloud Messenger (1914).

Sāvitri is a more engaging opera than At the Boar’s Head, an anecdote that ingeniously sets parts of Henry IV to folktunes, or the disagreeable Wandering Scholar.

The score is Wagnerian, a through-composed myth drama in miniature, with text and music by the same hand.

Sita, Holst’s earlier Indian opera, was derivative Wagnerism, imitating the orchestral bombast of the Ring.

Sāvitri is the Wagner of Parsifal: austere yet beautiful. It is a chamber opera: only half-an-hour long; calls for three singers, a female chorus, and an orchestra of twelve; and has no orchestral accompaniment until page three of the score.

The finest passages include Sāvitri’s premonition of Death coming for her husband; Satyāvan’s description of the world as Māyā; and Sāvitri’s greeting to Death.

The opera works on two levels, as a simple story of wifely devotion and cleverness, and a mystical tale of a woman unfettered by Māyā (illusion).

“Unto his kingdom Death wendeth alone. One hath conquered him, One knowing life, One free from Māyā. Māyā who reigns where men dream they are living, Whose pow’r extends to that other world where men dream that they are dead. For even death is Māyā.”

You must have been waiting for me to do Padmavati, it was up for less than five minutes and already I have a view and a like! Thanks!

I actually heard Savitri first and then remembered that I had Padmavati on the list so I completed it all in about 2 hours. I like the story of Savitri more than the music (maybe a little too minimalist for me, although there were three sections where I really liked the orchestral/choral effect.

LikeLike

Well, you’re one of half a dozen I visit… But the only opera blog!

Oh, for your beaux yeux bleus!

As for ﹰLakme, maybe around #80? Next on the list is Verdi’s Ballo (no points for guessing the sequel), and I need to familiarize myself with Butterfly for work. Watched a video 12 years ago, when I was getting seriously into opera.

LikeLike

Oh great I love Ballo! Can’t wait.

LikeLike

Yeah, it’s brilliant, isn’t it? Inventive, eclectic score, full of comedy and tragedy – and very French!

Speaking of French… The Paris HUGUENOTS will be broadcast in cinemas. First time, as far as I know, Meyerbeer has been. I’m hoping it’s a great production.

LikeLike

This might interest you: https://operascribe.com/2018/08/05/76-a-masked-ball/

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this opera, which crams so much into its short length. I even saw it staged once, when I was very young. I remember very little about it other than that the set design was dominated by a huge moon which the stage director and designer (John Morton) ingeniously managed to change to a sun during the course of the opera without our noticing, so involved and rapt was our attention on the action.

I have the Janet Baker recording you detail above, which could hardly be bettered.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When and where did you see it?

I’d love to see it myself; it’s an imaginative little opera.

LikeLike

It would probably have been around 1970, given by the semi-professional Durham Opera Company. Though many of the singers were amateur, the orchestra, conductor and producer were all professionals, and many of the singers went on to have professional careers. IIRC, the other opera on the bill was Menotti’s The Old Maid and the Thief, but it didn’t make anything like as much impression on me as Savitri, which still haunts my memory.

LikeLike

I have the lingering memory that you’re based in Sydney. This may or may not be true; but in any case, I thought it might interest you to note that this will be done in Sydney in February (www.thecooperativeopera.org).

The CoOPERAtive are also doing Iphigénie en Tauride in April!

LikeLike