IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA, OVVERO LA PRECAUZIONE INUTILE

- Opera buffa in 2 acts

- Composer: Giovanni Paisiello

- Libretto: Giuseppe Petrosellini, after Pierre Beaumarchais

- First performed: Imperial Court, St Petersburg, 26 September 1782

| COUNT ALMAVIVA | Tenor | Guglielmo Jermolli |

| ROSINA | Soprano | Anna Davia de Bernucci |

| DON BARTOLO | Buffo | Baldassare Marchetti |

| FIGARO | Baritone | Giovanni Battista Brocchi |

| DON BASILIO | Bass | Luigi Pagnanelli |

| GIOVINETTO [Youth], Bartolo’s aged servant | Tenor | |

| SVEGLIATO [Vigilance], A sleepy servant | Bass | |

| NOTARY | Bass | |

| WARDEN | Tenor | |

| Quartets of Alguazili (constables) and servants | Chorus |

SETTING: Dr. Bartolo’s house, Seville

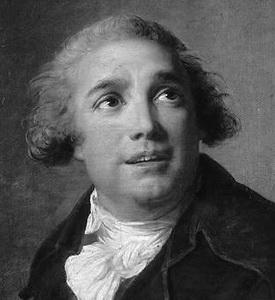

Paisiello ( (1740–1816) occupies a footnote in history as the composer of the first Barber of Seville. In his day, this Neapolitan composer was well regarded. Quickly making a name for himself with opera buffa in the 1760s (including Il marchese di Tulipano, a European hit), he dominated the Italian opera houses once Piccinni went to France.

The crowned heads of Europe him. He was court composer to Catherine the Great for nine years. He composed a Passion for Stanislas August of Poland, and two symphonies and an opera for Joseph II of Vienna. He was Napoleon’s favourite composer; he composed the mass for his coronation, served him as chapel master, and received the Légion d’honneur. He served Ferdinand IV of Naples and his successor, Joseph Bonaparte.

Few Italian composers wrote with as much charm for the human voice, Clément thought; Fétis considered he had less verve than Guglielmi, fewer ideas than Cimarosa, but more charm and expression. He had, though, the reputation of an intriguer – including plotting against the brilliant young Rossini. Perhaps he felt threatened by his Barbiere di Siviglia.

Il barbiere is the second Paisiello opera I’ve heard. (I reviewed Nina very early in this blog’s life.) Neither impressed me. Paisiello is conventional. He seems always to find the most obvious, least interesting notes or phrase. This might explain his popularity with Europe’s rulers; his music is undemanding, simple fare, that a monarch can listen to after a long day of strategy and warfare, without having to concentrate.

Paisiello composed his Barbiere for Catherine the Great’s court in 1782, Beaumarchais’s 1775 play had been performed there a couple of years before. The libretto is little more than a translation of the play; there are few recitatives (since the Russians didn’t understand Italian), but as much music as Paisiello wanted, in the Naples manner: “tormented, varied music with lively harmonic passages with accidentals in it”. It was not a hit when first performed in Italy on Paisiello’s return home; audiences complained that in it, and his other Russian operas, the cold of the north had entered. Paisiello revised it, and the Barbiere was widely performed throughout Europe from 1783, until – unsurprisingly – overshadowed by Rossini’s famous work. There were rare productions in Paris (1868 and 1889), Venice (1875), Berlin (1913), Monte Carlo (1918), and Milan (1939).

It is, frankly, something of a bore, even when one tries valiantly to forget Rossini. Compared to him, it’s stodgy and uninspired. For every piece here, Rossini’s equivalent is better: more imaginative, wittier, full of brio.

The overture is cheerful, sprightly, but not in Rossini’s class. The first act contains the Count’s cavatina “Saper bramate”, where, accompanying himself on a guitar, he tells Rosina he is Lindoro; it was the opera’s most famous number. A spirited allegro presto duet for the Count and Figaro finishes the scene. The second scene contains the yawning and sneezing trio; it’s a notable curiosity, but it’s overlong, and lacks the fizz Rossini or Offenbach would give it. Recommended to people who enjoy hearing noses blown in stereo. The Count, disguised as a soldier, slips his billet-doux to Rosina in an allegro trio; the act ends not with a stretta finale, but a cavatina for Rosina.

The second act has a quintet, with a brisk allegro presto section (“Meraviglia mi fate, signore”), and a lively finale.

SUGGESTED RECORDINGS

- Listen to: Pietro Spagnoli, Antonino Siragusa, Luciano di Pasquale, Angelo Nardinocch, Anna Maria Dell’Oste, Donato Di Gioia, and Stefano Consolini, with Giuliano Carella conducting the Trieste Teatro Verdi Orchestra and Chorus, 2000. Dynamic CDS417.

- Watch: M.G. Bonelli, A. Safina, L. Casarin, G. Spinelli, L. Regazzo, P. Ruberti, and C. D’Adamo, with Gregorio Goffredo conducting the Accademia lirica mantovana, Mantua, 1989. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8UQ_cy57VE

WORKS CONSULTED

- Félix Clément, Les musiciens célèbres depuis le 16ème siècle jusqu’à nos jours, Paris : Librairie Hachette & Cie, 1878

- F.-J. Fétis, Biographie universelle des musiciens (2ème édition), Paris : Librairie de Firmin Didot Frères, Fils et Cie., 1869

- Stefano Olcese, introduction to Dynamic’s Barbiere.

I’m not surprised by these criticisms against Paisiello’s Barbiere because it’s a masterwork coming from the opera buffa tradition which is barely played or recorded nowadays, unlike the German singspiels or the Italian romantic operas. The importance of the orchestra is limited and vocal virtuosity is most often avoided. Paisiello’s Barbiere is a delicate and refined piece full of invention, memorable arias and melodic beauty. It was widely admired in his time including by Wolfgang and Leopold Mozart and by Hadyn who represented it in Eszterhazà without any change unlike most Italian operas. Ears change but masterworks remain.

LikeLiked by 1 person