- Romantic Opera in 3 acts

- Composer: Sir Arthur Sullivan

- Libretto: Julian Sturgis, after Sir Walter Scott

- First performed: Royal English Opera House, London, 31st January 1891

| RICHARD CŒUR-DE-LION, King of England | Bass | Norman Salmond and Franklin Clive |

| PRINCE JOHN | Baritone | Richard Green and Wallace Brownlow |

| SIR BRIAN DE BOIS GUILBERT, Commander of the Knights Templar | Baritone | Eugène Oudin, François Noije, Richard Green |

| MAURICE DE BRACY | Tenor | Charles Kenningham |

| LUCAS DE BEAUMANOIR, Grand Master of the Templars | Bass-baritone | Adams Owen |

| CEDRIC THE SAXON, Thane of Rotherwood | Bass-baritone | David Ffrangcon-Davies and W. H. Burgon |

| WILFRED, KNIGHT OF IVANHOE, his son | Tenor | Ben Davies and Joseph O’Mara |

| FRIAR TUCK | Bass-baritone | Avon Saxon |

| ISAAC OF YORK | Bass | Charles Copland |

| LOCKSLEY | Tenor | W. H. Stephens |

| THE SQUIRE | Tenor | Frederick Bovill |

| WAMBA, Jester to Cedric | Non-singing | Mr. Cowis |

| The Lady ROWENA, Ward of Cedric | Soprano | Esther Palliser and Lucille Hill |

| ULRICA | Mezzo-soprano | Marie Groebl |

| REBECCA, daughter of Isaac of York | Soprano | Margaret Macintyre and Charlotte Thudichum |

SETTING: England, 1194

One might well call Ivanhoe a “respectful operatic perversion” of Scott. The magnificent, sprawling 1819 novel gave the 19th century many of its romantic notions of mediaeval England: good King Richard and bad Prince John; Norman tyranny and suffering Saxons; Robin Hood and Friar Tuck; damsels in distress and knights in shining armour.

Ivanhoe is the son of the Saxon thane, Cedric of Rotherwood; his father has disowned him because he fell in love with Cedric’s ward, Rowena, who is of royal blood, and whom her guardian wishes to marry Athelstane, claimant to the English throne. Ivanhoe returns incognito and helps to restore Richard the Lion-heart to the throne. But the true heroine is the Jewess Rebecca, whom Scott modelled on the American philanthropist and educator, Rebecca Gratz. In many ways, the Jews are wiser and more peaceful than the Christians, who spend their time persecuting Jews for their riches and trying to burn them for witchcraft. “Far less cruel are the cruelties of the Moors unto the race of Jacob than the cruelties of the Nazarenes [Christians] of England,” Rebecca reflects. Even a sympathetic Christian like Ivanhoe recoils when he discovers that the beautiful, gentle woman who has nursed his wounds is Jewish.

As a truly English work, Sir Arthur Sullivan considered Ivanhoe the ideal subject for his first and only grand opera. Since the mid-1880s, David Lyle notes, he had wanted to write a “historical work” with music that spoke “to the heart, and not to the head”, and a plot that “[gave] rise to human emotions and human passions”.

By 1891, Gilbert and Sullivan had written twelve Savoy Operas – including the more serious historical work, The Yeomen of the Guard (1891) – but their partnership had foundered on the rocks of the Carpet Quarrel. After Gilbert took his former partner and the impresario D’Oyly Carte to court, librettist and composer were on bad terms. That vein of comic opera seemed to have dried up for good; now was the time for Sullivan to prove his mettle with a serious work, as his admirers and his critics had wished him to do for years. When the monarch herself requested Sullivan compose an opera of Ivanhoe, he had no choice but to yield in Queen Victoria’s name.

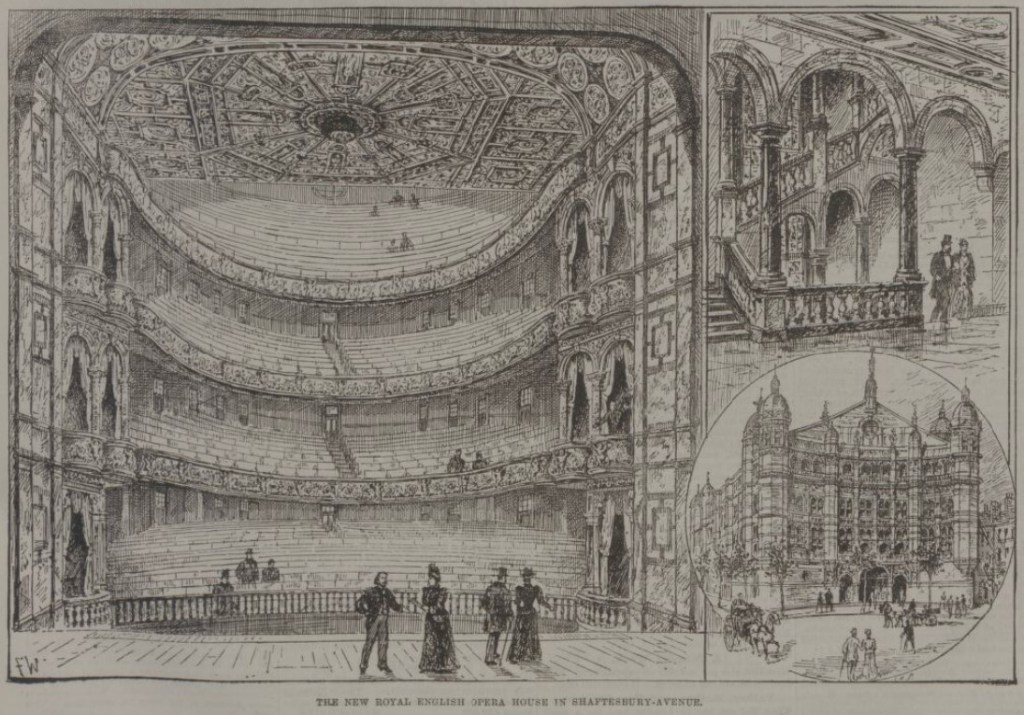

D’Oyly Carte built a new home for English grand opera, the Royal English Opera House, which Sullivan’s work inaugurated. Ivanhoe ran for 155 performances – the longest unbroken run of a serious opera – but it lost money, and the theatre closed almost a year later. (Today, it is the Palace Theatre, a popular London venue for musicals.) Sullivan patched up his quarrel with Gilbert, and the pair produced two more works, neither of which recaptured their old popularity.

Ivanhoe was critically acclaimed at the time, except by George Bernard Shaw, who objected that “a good novel [had been] turned into the very silliest sort of sham ‘grand opera’”. Attempts to revive it since, however, have been largely unsuccessful. Reviewing a 1910 production, The Times called the work “curiously loose-limbed and wanting in force and concentration”.

Today, it has some admirers. Lyle staged it in Edinburgh in 1999 (Act I, scene 3 and Act II, scene 1 on YouTube); he considers it “unjustifiably neglected”, “powerful and uplifting”, and “an important landmark in the history of British opera”. David Lloyd-Jones conducted it in 2009, with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales; Chandos’s recording was then named the BBC Music Magazine’s ‘Opera Choice’ for April 2010.

But for most listeners, Ivanhoe is a footnote to the Savoy Operas, a curiosity that would be entirely forgotten were it not by the composer of The Mikado.

Certainly, the libretto leaves much to be desired. Julian Sturgis condensed Scott’s 500-page novel into a three-act opera, omitting many major characters (Athelstane, Wamba the Witless, Gurth the swineherd, Reginald Front-de-Bœuf, and Prior Aymer), incidents (Prince John’s plot to usurp the throne), and themes (Christian anti-Semitism).

The result: highlights from Ivanhoe, rather than a coherent music drama. Shaw, for one, was scathing: in his view, the libretto was “fustian”; the book had been “gutted of every poetic and humorous speech it contains”.

But Sturgis’s liberties with the libretto were not a concern, as the Evening News pointed out. “The story, and its characters, are familiar as household words to nineteen Englishmen out of twenty, and … therefore, the great drawback of lyric drama, the constant interruption of the movement of the plot, and the consequent suspension of interest by intervals of purely decorative music, was very little noticeable.”

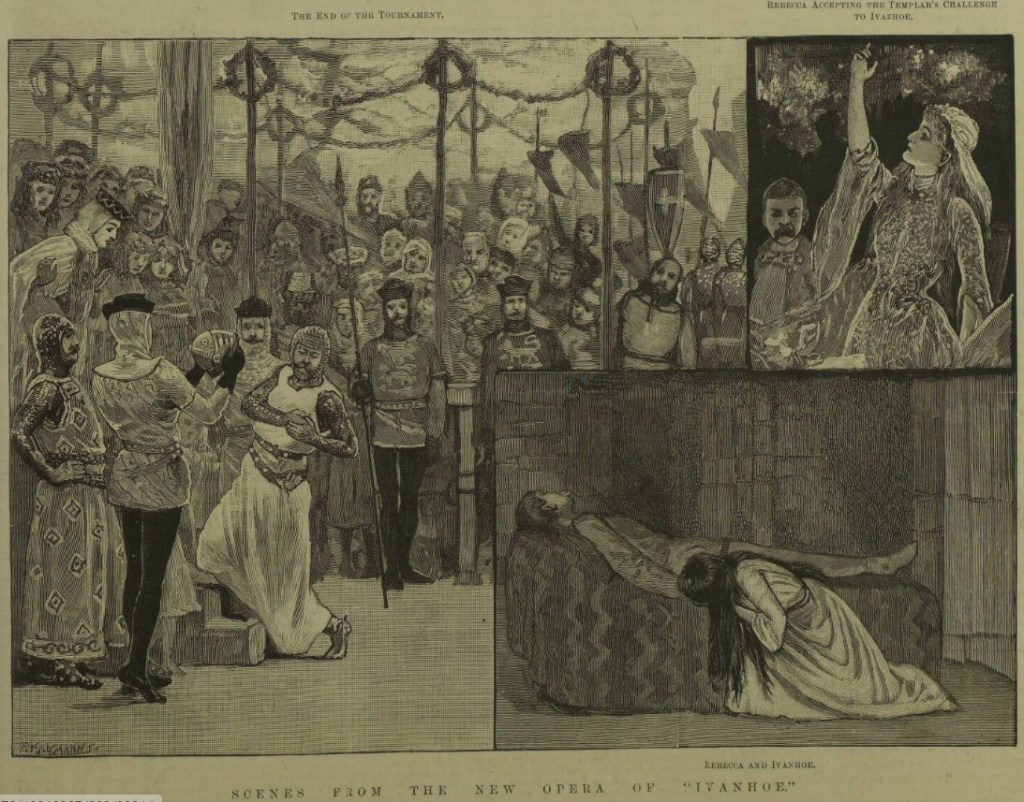

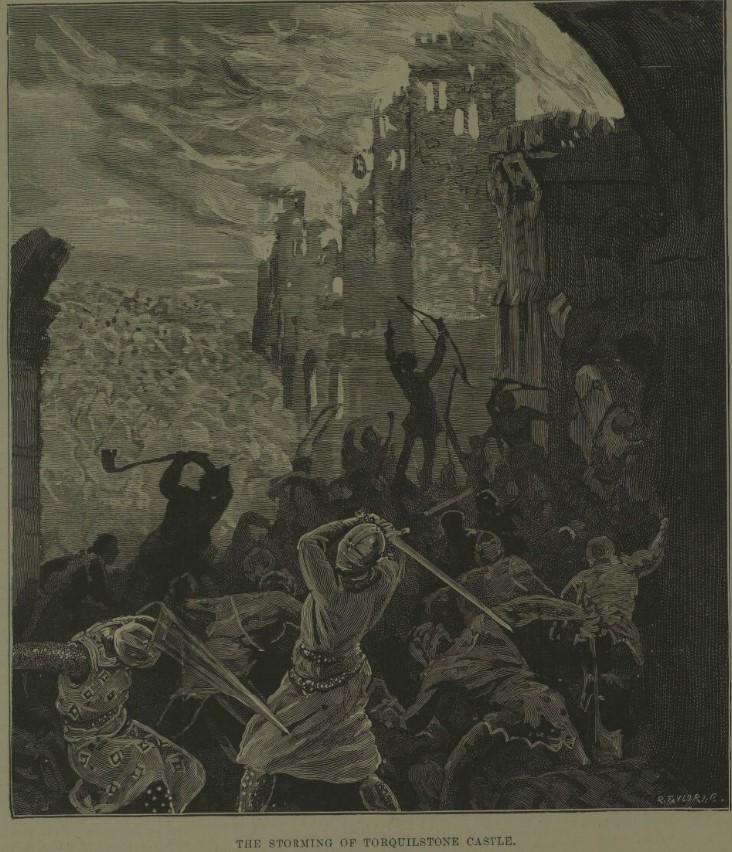

Instead, there were appeals to English patriotism (the opera ends with the royal banner of England raised over the Templars’ castle), and plenty of spectacle and pageantry, particularly the tournament at Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Act I (The Referee: “a truly grand picture of Saxon and Norman England”) and the storming of the castle and its fiery destruction in Act III (Daily News: “perhaps the most imposing spectacle the English operatic stage has yet witnessed”). That scene necessitated a 20-minute scene change in the middle of Act III, and the performance ran for four hours, from 8 o’clock till nearly midnight.

Nevertheless, the première, the critics almost all agreed, was a triumph. “English opera has been provided with a magnificent home; an essentially national story has been set to music by the most popular of native composers,” declared the Evening Standard. “The occasion was, indeed, an epoch in art… A great work had been added to the world’s possession of opera.”

Sullivan’s music was hailed as quintessentially English. “In spite of all temptations to belong to other nations – Wagner exhorting him to be unmelodious and to transfer what tunes he may have from the performers’ mouths to the orchestra, Gounod whispering him to leave all and follow Faust, Verdi and Ponchielli inviting him to be ‘that devil incarnate, an Englishman incarnate’ – Sir Arthur Sullivan remains an Englishman,” wrote the Illustrated London News.

The Pall Mall Gazette thought Ivanhoe was “a happy medium” between the “set forms” of the old-fashioned number opera and the “rhapsodical diffuseness” of Wagner. The Times detected the influence of Berlioz.

Perhaps the Daily News gave the fullest description of the opera’s musical style: “It is extremely rich in the lyrical element, although the various beautiful songs which Sir Arthur has provided are not dragged in inconsequentially, but grow naturally out of the situation. Free use is made of certain phrases representative of personages or events in the tale, but they are employed as ‘reminiscent themes’ rather than as leading motives, and always with judgement, discretion, and effect. Pretentious concerted pieces for the chief artists, of which Italian opera affords so many examples, the composer consistently avoids; while the only vocal trio and vocal quartet in the opera are by no means its happiest features. On the other hand, many of the choruses have the true British ring, and the dramatic situations are treated with a power which Sir Arthur has not before had an opportunity to display. Dialogue has been replaced by a species of melodious recitative, any monotony being avoided by varied accompaniments; the traditional operatic chorus … have been abolished in favour of ever moving crowds, and both in the music and the stage show there is a highly refreshing freedom from conventionality. As to the orchestration, although necessarily more elaborate than in comic opera, it shows abundantly that fertility of resource, warmth of colouring, and exquisite finish, for which all Sir Arthur’s scores are distinguished.”

The Graphic also thought the opera’s success depended on its lyrical element: the songs and duets were in Sullivan’s happiest manner, although the chorus had too little to do, and there were no complicated ensembles of the traditional operatic pattern – but the charms of melodies, allied with refined and effective orchestration, were undeniable.

Shaw, however, thought Ivanhoe was “disqualified as a serious dramatic work by the composer’s failure to produce in music the vivid characterisation of Scott, which alone classes the novel among the masterpieces of fiction”. “No, Sir Arthur, it may be very pretty and very popular, but it is not Ivanhoe.”

I find Ivanhoe a work of mixed inspiration; it is consistently well and conscientiously written, there are lovely melodies and grand choruses, but it is often lugubrious and long-winded.

Ivanhoe is through-composed, in the Wagnerian style; the unit is the scene, not the number, which gives Sullivan’s melodic muse less chance to shine than in the Savoy Operas. It is the heroic style of Princess Ida or the ‘Merrie Englishness’ of Yeomen of the Guard writ larger; elsewhere, one is reminded of the Savoy Operas’ sentimental tenor and soprano solos and love duets – these are (except for The Pirates of Penzance) the duller, more conventional parts of G&S.

Act I, scene 1 (Cedric’s banqueting hall) is perhaps the most Wagnerian: it is almost all lyrical declamation, except for Cedric’s vigorous, too short drinking song (which puts me in mind of Stephen Oliver’s music for the BBC Lord of the Rings). In scene 2, Rowena’s moon aria was well regarded at the time. Easily the act’s best music is in scene 3: the ‘Plantagenesta’ chorus, with its broadly flowing melody, while Ivanhoe’s entrance and the description of the off-stage joust with Bois Guilbert is exciting.

The best pieces in Act II are Friar Tuck’s “The wind blows cold (Ho, jolly jenkin)”, which rapidly became popular, and Ulrica’s “Whet the keen axes”, like an ancient cry of vengeance. Contemporary audiences were impressed by Bois Guilbert’s arioso; Rebecca’s prayer, “Lord of our chosen race”, based on a melody Sullivan heard at a Leipzig synagogue; and Rebecca and Bois Guilbert’s grand duet.

Act III opens with Ivanhoe’s lovely tenor aria, “Happy with winged feet”. The Templars’ hymn, “Fremuere principes”, is beautiful and sincere – and utterly inappropriate for Scott’s hypocritical, bigoted, and power-hungry knights. Otherwise, the act includes an aria for Rebecca, a quartet, and Rowena and Ivanhoe’s duet.

In many ways, Sullivan is his own worst enemy; one cannot help but compare Ivanhoe to the consistently more tuneful music he wrote for Gilbert. While interesting to hear, I doubt I will return to it as often as to the Savoy Operas.

And on that note, I’ve got a little list – my rankings of G&S:

- The Mikado

- The Pirates of Penzance

- Patience

- The Grand Duke

- Princess Ida

- Trial by Jury

- Iolanthe

- The Gondoliers

- The Yeomen of the Guard

- HMS Pinafore

- Ruddigore

- The Sorcerer

- Utopia, Ltd.

Listen to

Neal Davies (Richard Cœur-de-Lion), James Rutherford (Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert), Toby Spence (Wilfred, Knight of Ivanhoe), Janice Watson (The Lady Rowena), Geraldine McGreevy (Rebecca), with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, conducted by David Lloyd-Jones, 2009, Chandos.

Works consulted

- The Daily Telegraph & Courier, 31st January 1891

- The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 31st January 1891

- The Referee, 1st February 1891

- The Daily News, 2nd February 1891

- The Evening News, 2nd February 1891

- The London Evening Standard, 2nd February 1891

- The Pall Mall Gazette, 2nd February 1891

- The Times, 2nd February 1891

- Truth, 5th February 1891

- The Graphic, 7th February 1891

- The Illustrated London News, 7th February 1891

- The Queen, 7th February 1891

- George Bernard Shaw, London Music, 4th, 11th February, and 11th November 1891, Gilbert & Sullivan Archive

- The Times, 9th March 1910

- David Lyle, “Notes on the Music”, Gilbert & Sullivan Archive

I’ve always been curious about this one, but never quite had the courage to dip in — especially after so many lukewarm reviews of this piece. I’m familiar with all of G&S, except The Grand Duke and Princess Ida, which you have listed as 4 & 5, so now I really am curious about those.

British opera is unjustly neglected, but when you hear it you really do understand what a blessing it is to not be able to understand what is being sung. Any time spent with Thomas Arne’s Artaxerxes confirms this. Long stretches of recitative expressing worry over the state of the heroine’s virginity and other antiquated concerns makes me laugh every time I hear it. And really I should just grow up.

Much more entertaining than Ivanhoe seems, and I really do recommend this campy gem of an opera (on Naxos, so it’s cheap), is Satanella (yes, it’s about a female demon) by Michael William Balfe. Conducted by the savior of British opera, Richard Bonynge. The plot is so absurd, but the music is pretty wonderful. And there are choruses of bridesmaids, party guests, pirates (!), slave traders (!), demons (male and female) and angels, so lots of numbers involve choruses. And Satanella (her real name) is in disguise a lot: a page boy and the Sultana of Tunesia, and other things I can’t remember. In spite of arranging to have the object of her affections’ fiancee kidnapped by pirates and sold into slavery, said fiancee forgives her, presenting her with a rosary, and she becomes an angel and ascends to Heaven (accompanied by a chorus of cheering angels and catcalling demons). It really must be heard to be believed. The only drawback is that the recording omits the spoken dialogue, but the complete libretto is available from Naxos’ website.

LikeLike

Satanella sounds good fun. (Classics Today’s review makes it sound like a possible camp classic.) Shades of Robert le Diable and Halévy’s ballet La tentation? I’ll add it to my list. Thanks!

Princess Ida is Sullivan in more serious mode – the heroine’s music is “operatic”, there’s a fine quartet, and a couple of grand opera finales. For comic relief, two trios of three hulking brothers (“Like most sons are we, masculine in sex”), patter songs about women’s education and Darwinian man, and petulant King Gama (“Yet everybody says I’m such a disagreeable man – and I can’t think why!”).

The Grand Duke is flawed, but I love it. Gilbert’s libretto is overstuffed with ideas, but it’s very tuneful. It contains a sausage roll aria, a patter song in Greek, a roulette aria, and a chorus that gets drunker and drunker. (The opening number, though, is weak; much of the music for the soubrette is dreary.)

LikeLike

Which recordings do you recommend? I am partial to the D’Oyly Carte recordings from the 60s because they were my introduction to G&S, but currently PI and GD are only available as part of the whole shebang, not sold separately. I appreciate Ohio Light Opera, and with those recordings you get all the dialogue, but some are better than others.

LikeLike

Which recordings do you recommend? I am partial to the D’Oyly Carte recordings from the ’60s/’70s because they were how I discovered G&S. Currently, their recordings of PI and GD are only available as part of the whole shebang, and I already own the others. Ohio Light Opera? They get mixed reviews, but you get all the dialogue (I really love their recordings of Victor Herbert). The only other recordings I see are by a group called The Lamplighters, but I’ve never heard of them.

LikeLike

Oh, the ’60s / ’70s G&S, with John Reed and Kenneth Sandford.

Princess Ida:

Grand Duke: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yB7lp1V6VvM

The 1966 BBC recordings are also supposed to be good:

https://www.talkclassical.com/threads/opera-in-english-radio-broadcasts-in-the-public-domain.53537/page-6#post-2087493

LikeLike

Thank you! I always forget about YouTube.

LikeLike

It’s nice to see Ivanhoe getting a bit of attention. It’s not perfect, but it’s still a very enjoyable work. I think I rate it slightly higher than you, but otherwise I agree with your assessment in most every respect, you even listed all of my favorite parts among your highlights. As Shaw said, the opera’s biggest flaw is that doesn’t have much of the Great Scott in it. I first read Ivanhoe when is was 13, and I was absolutely enraptured by it. The opera just doesn’t have the same effect, though considered on its own merits it’s still quite good.

Have you heard Sullivan’s The Beauty Stone? The libretto’s not great (at least in the spoken bits. The authors overindulged in pseudo-medieval dialogue, but kept it to a minimum in the sung parts), but Sullivan’s score is excellent. It’s well worth a listen.

(Regarding you ranking of the Savoy operas, great to see The Grand Duke and Patience so high up! But Iolanthe at seven? And Ruddigore at eleven?! Say it isn’t so! I’ve never been able to come up with a ranking, but my favorites are the aforementioned four plus The Gondoliers and Yeomen. (Ok, and Trial by Jury. But that’s a full half of their operas, which kind of negates the point of picking favorites.) I’ve never understood why some people look down on G&S as “not real opera.” If you ask me, Sullivan was better than Strauss and every bit the equal of Offenbach.)

LikeLike