- Opéra-ballet in 2 acts

- Composer: Albert Roussel

- Libretto: Louis Laloy

- First performed: Théâtre de l’Opéra (Palais Garnier), Paris, 1st June 1923, conducted by Philippe Gaubert

| PADMÂVATÎ | Contralto | Ketty Lapreyette |

| RATAN-SEN, King of Chittor | Tenor | Paul Franz |

| ALAOUDDIN, Sultan of the Moguls | Baritone | Édouard Roux |

| THE BRAHMIN | Tenor | Henri Fabert |

| GORA, Palace Steward | Baritone | Dalerant |

| BADAL, envoy of Ratan-Sen | Tenor | Mario Podestà |

| NÂKAMTI, young woman of Chittor | Mezzo | Jeanne Laval |

| The Watchman | Tenor | Soria |

| A Priest | Bass | Armand-Émile Narçon |

| Women of the Palace | Soprano Contralto | Marilliet Lalande |

| A Woman of the People | Soprano | Dagnelly |

| A Warrior | Tenor | Dubois |

| A Merchant | Tenor | Georges Régis |

| An Artisan | Baritone | Peyre |

| Warriors, Priests, Women of the Palace, Men and Women of the People | Chorus | |

| A Woman of the Palace A Slave A Warrior Kali Durga Prithivi, Parvati, Ouma, Gaouri | Dancers | A. Johnsson J. Schwarz G. Ricaux Lorcia Bourgat |

SETTING: Chittor, India, 1303

Visiting the ruins of Chittor (Chittorgarh), Rajasthan, in 1909–10 – in the company of Ramsay MacDonald, no less – the French composer Albert Roussel was struck by the legend of Alaud-Din Khalji, Sultan of Delhi, who besieged the fort for eight months in his pursuit of the beautiful rani, Padmini. When her husband, Ratnasimha, died on the battlefield, Padmini and her companions burnt themselves to death, thwarting the sultan’s intentions and safeguarding their honour. (I remember hearing similar stories about queens’ self-immolation, or jauhar, at Jaisalmer.)

In Roussel’s version, Ratan-Sen promises to give his wife to Alaouddin to save his people; Pâdmâvati, however, driven by her commitment to their marriage vows, stabs her husband, and then burns herself to death.

Padmâvatî is an opéra-ballet – reviving a French Baroque genre, created by Campra (L’Europe galante, 1697), and exemplified by Rameau’s Les Indes galantes (1735). The opera features extended dance sequences. In Act I, Ratan-Sen stages entertainments for the sultan (dances of warriors; slave girls; and of the palace women, with soprano vocalises). Act II takes place in the temple of Shiva, opening with an impressive prayer (“Siva … Om”). The opera culminates in Padmâvatî’s funeral scene: a dance and pantomime with appearances by the goddesses Kali and Durga, and the white and black daughters of Shiva, who transform into Apsaras. It is the sort of apotheotic finale Meyerbeer envisaged for L’Africaine (1865). The choruses in Sanskrit predate Philip Glass’s Satyagraha (1980) by six decades.

Louis Schneider (Le Gaulois) was struck by the spectacle. “Never has the Opera produced more beautiful visions than the two tableaux of Padmâvatî. These green warriors, these dancing women who cover their shoulders with multicoloured shawls spangled with silver, these women who seem to be chained to each other by garlands of lotus flowers, this crimson queen who casts a bloodstain on this vibrant backdrop, all this is like the Thousand and Second Night.”

Because Padmâvatî depends for much of its effect on ballet and spectacle, one misses an essential component of the work when listening to an audio recording alone. This makes it hard to come to any firm conclusion about its merits as an opera.

Nor is the music very memorable. Impressionism, largely in minor keys, is not my favourite style; I prefer music that is clearer and more tuneful. Nevertheless, Padmâvatî‘s score is an intriguing combination of Western and Indian approaches. The score, often polyphonic and dissonant, is strongly influenced by ragas. It reminded Charles Malherbe (Le Temps) of “a river in whose foamy eddies the fleeting reversed images of a strange temple and a corner of the jungle are reflected. The author of Évocations [1910–11] has made a long and profitable trip to mysterious India. He brought back to us, in an immense and disturbing cargo, the products and the graces of Hindu music.”

Padmâvatî’s lament (“Les dieux ne m’écoutent plus”), at the end of Act I, is sung in a languorous Hindu scale. That is the first time we hear the rani sing, more than halfway through the opera. Act I, however, also contains Nâkamti’s D flat aria praising the rani’s beauty (“Elle monte au ciel où rêve le printemps”), and the Brahmin’s curse and murder. For the most part, the vocal writing predominantly emphasises declamation, while the music aims more at creating mood than earworms.

The libretto was written by Louis Laloy, sinologist and Secretary General of the Paris Opéra, based on La légende de Padmanî, reine de Tchitor, Théodore Marie Pavie’s 1856 translation of Malik Muhammed Jasayi’s Padmavat (1540).

Roussel began composition in 1913, but the work was not performed until 1923, a decade later. It was a reasonable success at the Opéra, attaining 39 performances by 1947.

Its admirers included Paul Dukas, who wrote: “M. Albert Roussel possesses instinctively, and to the highest degree, a feeling for mass movements and collective passions. I know of nothing more ardently animated than the rhythmic dance of the palace women in the first act of Padmâvatî, nothing more fiercely tumultuous than the scene which closes it, nothing more quivering with sacred horror than the impressive funeral ceremony that crowns this beautiful work, and where all the powers of Death and Life are exalted, engendering each other eternally.”

Henry Malherbe (Le Temps) praised the opéra-ballet as an artful, tasteful, pleasurable, and magical spectacle. Paul Bertrand (Le Ménestrel), however, regarded the work as an ingenious but sterile attempt to revive the 17th century genre. While the audience was interested, spellbound, astonished, they were never emotionally moved. The music seemed like a prestigious symphony that accompanied a magnificent spectacle, but it did not fulfil the inescapable conditions of musical theatre. The rhythmic element was rich, but the thematic and melodic element was rudimentary.

The opera was staged internationally after World War II, including in Buenos Aires, Naples, and London.

Suggested recording

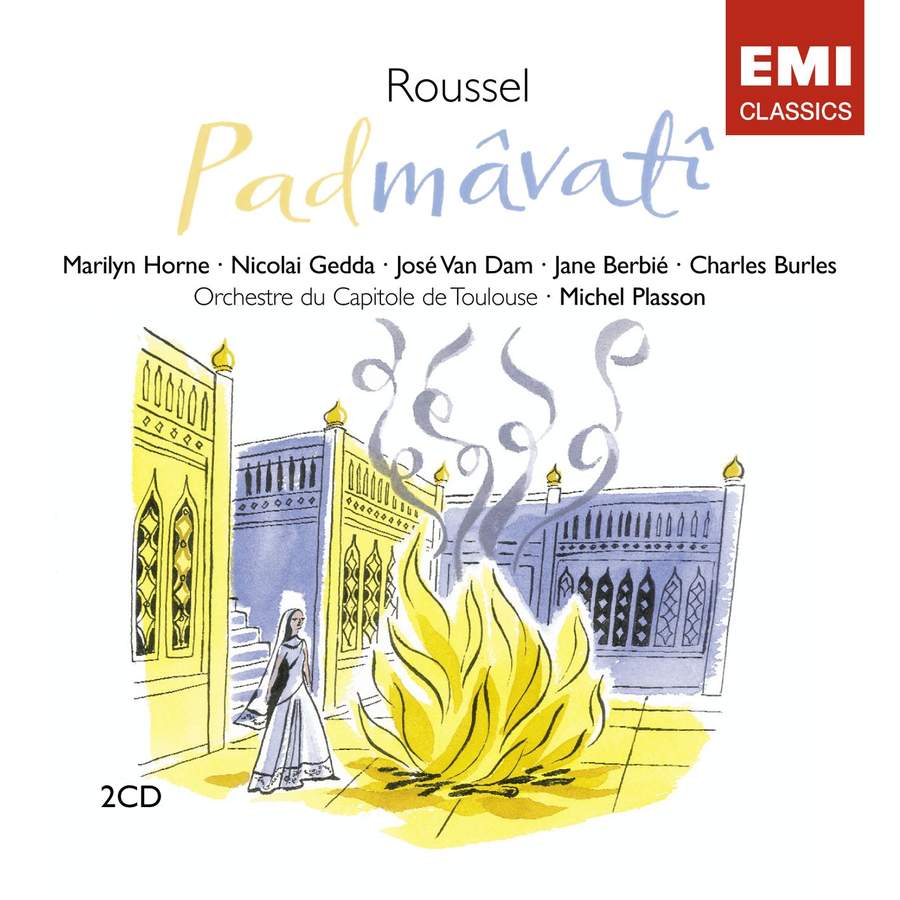

Marilyn Horne (Padmâvatî), Nicolai Gedda (Ranat-Sen), and José van Dam (Alaouddin), with the Toulouse Capitole Orchestra, conducted by Michel Plasson, Toulouse, 1982–83. EMI.

Works consulted

- Louis Schneider, Le Gaulois, 3 June 1923

- Charles Malherbe, Le Temps, 6 June 1923

- Paul Bertrand, Le Ménestrel, 8 June 1923

- Jean Poueigh, La Rampe, 17 June 1923

- Raymond Balliman, Lyrica, 1 July 1923

- Gustave Samazeuilh, Le Monde illustré, 28 August 1937

- Piotr Kaminski, Mille et un opéras, Paris : Fayard, 2003

- Vincent Giroud, French Opera: A Short History, Yale University Press, 2010

See also Phil’s Opera World.

Was this recording from a live performance? Because I’m trying to picture Marilyn Horne ballet dancing.

LikeLike

No; studio, as far as I know. I can’t imagine a lot of singers doing the Dance of the Seven Veils either. (Or what Spike Milligan called the Dance of the Seven Army Surplus Blankets…)

LikeLike