- Grand opera in 3 acts with a prologue

- Composer: Fromental Halévy

- Libretto: Eugène Scribe, after Shakespeare; translated into Italian by P. Giannone

- First performed: Her Majesty’s Theatre, London, 7 June 1850, conducted by Michael Balfe.

- First French performance, in 2 acts: Théâtre-Italien, Paris, 25 February 1851.

| ALFONSO, King of Naples | Tenor | Lorenzo Salvi |

| PROSPERO, Duke of Milan | Baritone | Filippo Coletti |

| ANTONIO, his brother, the usurper | Frederick Lablache | |

| FERDINAND, Prince of Naples | Tenor | Carlo Baucardé |

| TRINCULO | Signor Ferrari | |

| STEPHANO | Soprano | Teresa Parodi |

| SYCORAX | Contralto | Ida Bertrand |

| SPIRIT OF THE AIR | Mlle Giuliani | |

| ARIEL | Ballerina | Carlotta Grisi |

| CALIBAN | Bass | Luigi Lablache |

| MIRANDA | Soprano | Henriette Sontag |

SETTING: Prospero’s island

La Tempesta, Halévy’s Shakespearean opera in Italian, written for London, was performed at the Wexford Opera Festival in October, the first production in 170 years. I feel like I’m looking a gift horse in the teeth – the resurrection of any Halévy is cause for celebration, and I had listed La Tempesta as an unfairly neglected opera – but this work is very disappointing.

La Tempesta was the second opera presented at Her Majesty’s Theatre, after Verdi’s I masnadieri (1847). With the opera house’s fortunes ailing after his Benjamin Lumley, the impresario, had commissioned Eugène Scribe to turn Shakespeare’s romance into an opera (which would, of course, be translated into Italian for London). It is a loose adaptation: Caliban uses magic flowers to overcome Ariel and Miranda, and Sycorax makes Miranda believe Ferdinand is her enemy, and try to kill him.

Lumley had wanted Felix Mendelssohn to compose the music. When Mendelssohn died in early 1847, after refusing to set the text, Lumley engaged Halévy to write the music.

In the late 1840s, Halévy was at the peak of his career. He had achieved two of the biggest successes in the history of the Opéra-Comique: Les Mousquetaires de la reine (1846) and Le Val d’Andorre (1848), and another hit with La Fée aux roses (1849). Halévy was still, however, little-known in England. La Juive (only two performances) and Les Mousquetaires (mixed reactions) had been given there in 1846; and Le Val d’Andorre (not to English taste) in 1850.

Halévy was skilled at writing in the Italian style: he had worked as maestro al cembalo at the Théâtre Italien (1827–29), and composed a Rossinian opera semiseria, Clari (1828), for Maria Malibran. He also sent up the fad for Rossini in Le dilettante d’Avignon (1829). But I am reminded of the Trio italien in Offenbach’s M. Choufleuri restera chez lui le… (1861), and its suggestion that Italian opera is an assemblage of stock gestures and vocal display.

The score comes across as a pastiche of Italian opera; almost everything seems a memory of Rossini or Donizetti: a choral preghiera, the prima donna’s cavatina (stock vocalises), trios, choruses, love duets (with harp), drinking songs, inappropriately cheerful tunes (Prospero’s aria in Act III: “Unrelentingly, I will punish you… I am as unrelenting as the god of Cain…”), and even a prima donna finale aria (vocal display / coloratura) of the sort found in Italian opera 25 years before.

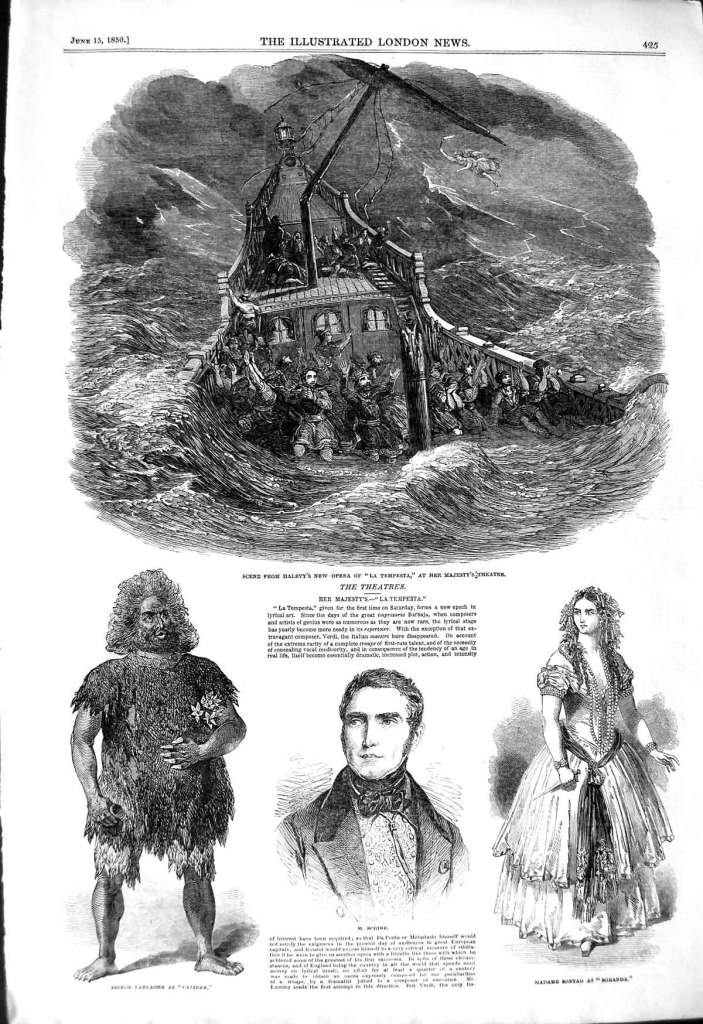

The storm scene at the start was much admired in 1850; it contains some Mendelssohnian string writing, but contemporary claims that it ranks with the best passages of La Juive are exaggerated. Otherwise, only the occasional bit of orchestration or melancholy phrase reminds us that this is Halévy (e.g., Miranda’s aria in the Act II finale, parts of her Act III duet). It is skilfully done – but what is the point of Halévy writing competent bel canto when he could have written authentic Halévy?

Charles Jernigan (Donizetti Society) suggests this was deliberate. In his view, Lumley “asked Halévy to write his opera in the style of Italian works of the primo ottocento, that is a traditional numbers opera, with cavatinas, cabalettas, and ornate, embellished vocal lines à la Rossini, combined with rousing choruses, drinking songs and the like … [because] London audiences (Lumley thought) were more attuned to operas of the 1830s and 1840s than more recent ‘noisy’ works by composers like Verdi”.

Halévy could do much, much better than this. But it pleased the bad taste of the conservative English public, while the French press favourably reviewed their compatriot’s latest work.

The Sun declared it was “the most beautiful grand opera and the most superb spectacle ever produced on the English lyrical stage”, and predicted that the first night would be long celebrated in musical annals. The Daily News thought the opera was Halévy’s chef d’oeuvre. “It is the work of a poet as well as a musician. Like all Halévy’s work it is profound in thought and masterly in construction, while it is bold, free, imaginative and dramatic, with a great deal of expressive melody, set off by the most varied and elegant instrumentation.” The Illustrated London News thought “Such a truly artistic work has seldom been seen on any stage; it is full of charming contrasts, employs every resource of modern art, and is free from all that is meretricious, glaring, and noisy”. P. A. Fiorentino, the critic for Le Constitutionnel, considered it a virile work, produced in all the maturity of talent.

Other critics, however, The Musical World and Henry Chorley (not a fan of Halévy’s) among them, found fault with Halévy’s music and with Scribe’s treatment of Shakespeare. The Morning Herald thought it was unlikely to raise or lower Halévy’s reputation: the music was well planned for effect, being clothed with a broad dramatic colour, but it lacked melody, and the arias were mechanical.

The composer’s brother, Léon, argued that the opera contained genuine beauties (particularly in Caliban’s role), but this English opera with an Italian poem based on an English play did not have a clear colour; the work was brilliant but composite; without damaging Halévy’s reputation, it added nothing to it.

Lumley had assembled a star cast: the bass Luigi Lablache as Caliban, “the most unique and fully embodied impersonation of the modern operatic drama” (Morning Chronicle); Henriette Sontag as Miranda; and the ballerina Carlotta Grisi as Ariel.

But the triumph of La Tempesta only lasted 13 performances. The run ended on 1 August when Grisi left the cast. “La Tempesta could not live,” Chorley snarked. “In England, as yet, Halévy has no public.” In the event, La Tempesta was only a stay of execution for Her Majesty’s; the theatre closed two years later.

In February 1851, Lumley staged the work in Paris, at the Théâtre-Italien, against Halévy and Scribe’s wishes. It was performed in an abridged version: almost all of Act III was cut, and the dénouement was moved to the end of Act II. Lablache and Sontag reprised their rôles. The first night started badly: Carolina Rosati, the ballerina portraying Ariel, fell into a trapdoor, injuring herself, but she was able to continue the performance. La Tempesta closed after eight performances.

It was not given again until 2022. The Wexford version uses Halévy’s autograph score, in which the rôle of Ariel is sung, rather than danced.

Recordings

Watch: Nikolay Zemlianskikh (Prospero), Hila Baggio (Miranda), Jade Phoenix (Ariele), and Giorgi Manoshvili (Calibano), with the Wexford Festival Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by Francesco Cilluffo, Wexford, 2022.

Works consulted

Parts of this blog post are from Robert Ignatius Letellier and Nicholas Lester Fuller, Fromental Halévy and His Operas, 1842–1862, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2021.

- Léon Halévy, F. Halevy, sa vie et œuvres, Paris: Heugel, 1863

- Christopher Dean Hendley, “Fromental Halévy’s La Tempesta: A Study in the Negotiation of Cultural Differences”, Ph.D. thesis, University of Georgia, 2005

- Charles Jernigan, “Halévy’s La Tempesta: Wexford Festival, October/November 2022”, Donizetti Society Newsletter, 2022

- Ruth Jordan, Fromental Halévy: His Life and Music, Kahn & Averill, 1994

- The Morning Chronicle, 10 June 1850

- The Morning Herald, 10 June 1850

- The Sun, 10 June 1850

- Revue et gazette musicale, 16 June 1850

- P. A. Fiorentino, Le Constitutionnel, 16 and 23 June 1850

- Oscar Comettant, Revue et gazette musicale, 30 June and 14 July 1850

One thought on “234. La tempesta (Halévy)”