- Grand opéra in 5 acts

- Composer: Giacomo Meyerbeer

- Libretto: Eugène Scribe and Émile Deschamps

- First performed: Théâtre de l’Opéra (salle Le Peletier), Paris, 16 April 1849

| Le Comte d’OBERTHAL | Bass | Hippolyte Bremond |

| JEAN DE LEYDE | Tenor | Gustave-Hippolyte Roger |

| JONAS, an Anabaptist | Tenor | Louis Guéymard |

| MATHISEN, an Anabaptist | Bass | Euzet |

| ZACHARIE, an Anabaptist | Bass | Nicolas Levasseur |

| BERTHE, Jean’s fiancée | Soprano | Jeanne-Anaïs Castellan |

| FIDÈS, Jean’s mother | Mezzo | Pauline Viardot |

| Peasants, Anabaptists, soldiers, townsfolk, children |

SETTING: The countryside near Dordrecht in Holland; the town of Leyden; a forest in Westphalia; the town of Munster, in 1530.

175 years ago today, Le Prophète was first performed: one of the half-dozen greatest operas of all time. Qualified by its composer as a “sombre and fanatical” work, Le Prophète anticipates many of the troubles of the twentieth century: charismatic politicians and cults of personality; the manipulation of the masses and their grievances; the hijacking of religion and ideology for power and profit; revolution, social injustice, and class warfare. It is a disturbing drama of suicide bombers and self-proclaimed Messiahs, in which romantic love (that staple of opera) plays only a small part. And how on earth, one might wonder, did a Jewish composer get away with an opera in which the supposed messiah and son of God turns out to be a fraud and mass-murderer?

1848 was the year of revolutions throughout Europe, when the apostles of liberty and other dangerous doctrines called for a new heaven and a new earth. In France, the July Monarchy was overthrown, the king abdicated, and the Second Republic was declared. Within four years, its first president, Napoleon III, had abolished the republic, and declared himself emperor. One autocrat had replaced another.

Giacomo Meyerbeer was out on the streets in those tumultuous days of February 1848, watching “the progress of the unrest” with interest.1 The people stormed the Tuileries, and thousands of people surged backwards and forwards through its rooms. At the Royal Palace, furniture and books were thrown out of the windows, and burnt on a bonfire. Meyerbeer watched that “eerie and sad spectacle”, then went home, and worked on the stretta of the Anabaptist Sermon, the big crowd scene in Act I of his long-awaited third grand opéra.

A little over a year later, Le Prophète premièred. Like Les Huguenots, his epoch-making success of 1836, the opera takes place amidst the religious troubles of the sixteenth century, at the time of the Peasants’ War and the theocratic tyranny of John of Leyden, the messianic ruler of the Anabaptist Kingdom of Zion in Münster.

The historic John of Leyden, one Johan Beukelszoon (1509–36), was a tailor; in Scribe’s libretto, he becomes an innkeeper. When the Anabaptists, like Macbeth’s witches, prophesy that Jean will be king, he wants none of it; all he longs for are his fiancée Berthe’s love and domestic bliss. But Berthe is the vassal of the Comte d’Oberthal, who refuses to let her leave his estate. When she escapes, Oberthal holds Jean’s mother, Fidès, hostage, and threatens to kill her. To save her, Jean has no choice but to yield Berthe to Oberthal. His eyes open to the iniquities of the feudal system, Jean accepts the Anabaptists’ offer. At the head of an army of militant fanatics, he captures the city of Münster, and imposes an even worse tyranny. In the cathedral, he is crowned Prophet-King, neither conceived by nor born of woman – to the surprise and horror of his mother, whom he publicly repudiates. At the end, Jean, realising how he has been used by the Anabaptists, blows up the Münster palace with all his enemies inside, destroying them all in a purifying conflagration. Fidès joins him on the funeral pyre, and the two are reunited in death.

And that stretta? The setting of Act I is the Dutch countryside, near Dordrecht, in the mid-sixteenth century. For generations, the peasants have laboured for their feudal masters – until three Anabaptists come, sinister men in black, preaching a new gospel. “Ad nos, ad salutarem undam,” they intone: come and be baptised again. Their sinister melody coils itself around the listener like a snake. Like other demagogues throughout history, the Anabaptists promise to end the suffering of the masses: the peasants will be the owners of the fields they till, their hated overlords’ castles will fall to the level of the lowliest cottages, tithes and unfree labour will be abolished, and the feudal masters will become slaves. The peasants seize scythes, pitchforks, and pickaxes, and resolve to murder the oppressors. “O roi des cieux, c’est ta victoire,” they cry. Their grievances are justified, but the peasants have been manipulated by unscrupulous men, concerned only with amassing power and wealth. Just as in Revolutionary France, and as later in Communist Russia and China, the revolution of the masses, driven by resentment, ends in more bloodshed and suffering; the people are manipulated by those who promise them liberty, the demagogues (the political-intellectual class) become the new masters, and the enslavement of the people continues.

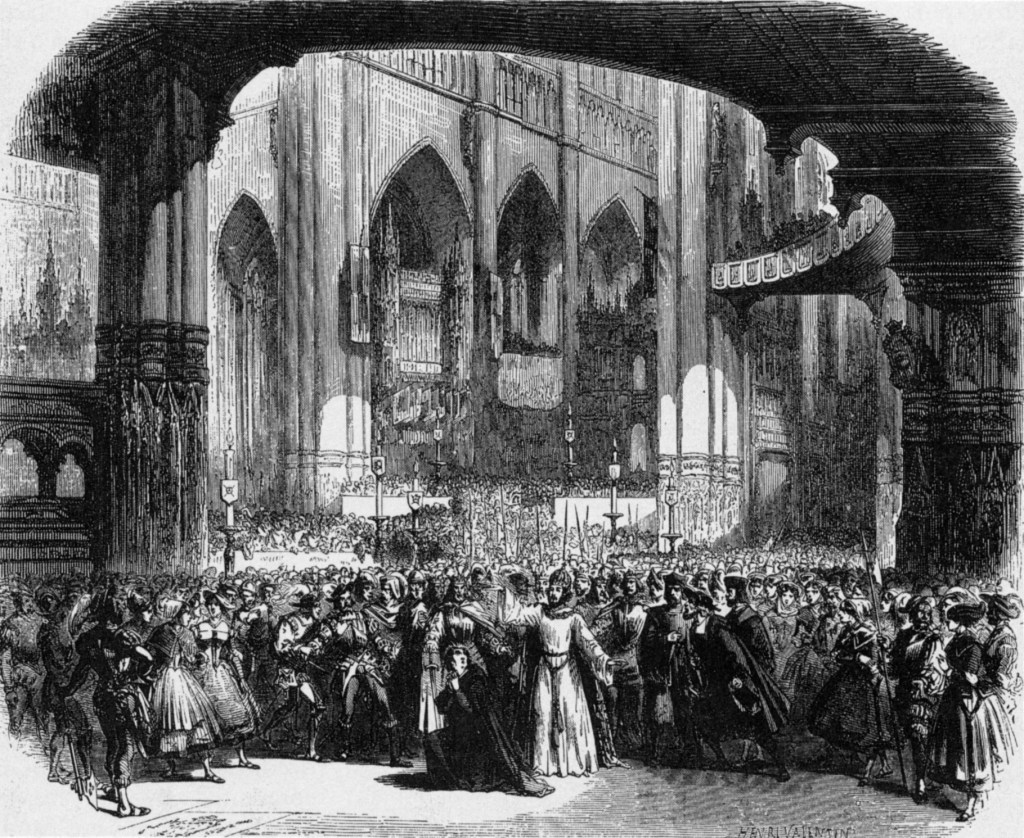

For Meyerbeer’s return to the French stage after a 13-year absence, the Paris Opéra created a blockbuster production featuring spectacular special effects: a ballet of ice skaters, like a Brueghel painting; the first use of an electric arc light in the theatre, mimicking the rising sun; one of the most grandiose scenes in all opera, the famous Cathedral Scene, admired by Verdi; and an enormous gunpowder explosion that blows up the Prophet’s palace at the end.

Le Ménestrel2 was amazed by the beauty, accuracy, and magnificence of the sets and staging. “The first tableau, with its gothic castle and windmills in perspective, resembles a painting by Dupré or Marilhat. The frozen lake in Act III ends in a misty horizon pierced in the distance by the steeples and buildings of Münster, undergoing the play and degradation of light from dusk to night, night to dawn, and dawn to the sun. Not a sun represented by a smoky lantern, but a real sun borrowing its rays from electric brilliance, almost rivalling the sun in the sky. The cathedral in Act IV and the palace hall in Act V offer, in a different style, scenes equally rich and well-arranged. And within these splendid settings, a whole world of soldiers, peasants, and lords, dressed in the picturesque costumes of the Middle Ages, comes to life. A marvel of invention and execution is the ballet of skaters, interspersed with highly original dances, in which Plumkett and Robert seized the chance to earn applause. The coronation scene and the feast scene, ending in a fire, outshine everything that opera has presented us with so far in terms of beauty and completeness.”

Le Prophète was both critically acclaimed and a worldwide success. Henri Blaze de Bury3 deemed it Meyerbeer’s masterpiece, and praised him as a painter, a musician of history. For Théophile Gautier4, it was the third part of “an immense symbolic trilogy, filled with profound and mysterious meaning; the three principal phases of the human soul are found represented there”: faith [in Robert le Diable, corresponding to the past, and taking the form of a legend], examination [in Les Huguenots, corresponding to the present, and taking the form of a chronicle], illumination [corresponding to the future, and taking the form of a pamphlet]. Meyerbeer’s operas, Fétis5 declared, were models of the art of kindling emotion, of exciting it, of sustaining it, and of gradually carrying it to its ultimate limits. His sympathies lay with powerful effects, but perhaps no musician had known as well as he how to make a homogeneous whole, gripping in grandeur, pomp, and energy. Le Prophète even surpassed the fourth and fifth acts of Les Huguenots; in the corridors of the Opéra, after the first few performances, people exclaimed: “I have never experienced such strong emotions from music!”

Le Prophète soon travelled around the globe, bringing audiences on five continents under its power. By the end of 1850, the opera had been staged in London, Germany, Vienna, Lisbon, Antwerp, New Orleans, Budapest, Brussels, Prague, and Basel; it would be performed as far away as South America, Australia, and Egypt. It was performed 573 times in Paris until 1912, and remained in the repertoires of Milan until 1885, London until 1895, Berlin until 1910, Vienna until 1911, New York until 1928, and Hamburg until 1929. It was, in fact, one of the most widely performed operas of the 19th century – and, Reynaldo Hahn6 famously said:

“People of my father’s generation would rather have doubted the solar system than the supremacy of Le Prophète over all other operas.”

Like all of Meyerbeer’s operas, it was banned in the Third Reich: the Jewish composer had exposed the mechanism of totalitarianism, and predicted and exposed how tyranny functions.

Even Wagner was (for a time) awed. “During this time,” he wrote to his friend Theodor Uhlig, “At this time I saw for the first time Le Prophète – the Prophet of a new world: I felt happy and elevated, gave up all vile plans that seemed so godless to me. Should genius arrive and throw us in other directions, an enthusiast will follow him everywhere, even if he feels himself incapable of achieving anything in this field.”7 He later changed his mind, savaging Le Prophète for its unmotivated “effects without causes”.

But many critics of the time – in contrast to Wagner’s polemics that damaged the composer’s reputation – praised Meyerbeer for his artistic sincerity. “In the midst of the political fever that torments us, it is reassuring to see a great artist dedicate a life of leisure and noble faculties to extending the pleasures of intelligence,” Paul Scudo8 (Revue des deux mondes) wrote. “A nature less strong and less serious than that of M. Meyerbeer might have slumbered in his acquired glory or only presented to the curiosity of the public light works that would not be the result of the deep and passionate meditation that characterizes M. Meyerbeer’s recent works. But the author of Les Huguenots believes in the truth of art; he pursues it with ardour, and as long as he seizes and embraces it, he cares little about the time and effort it has cost him. Like M. Ingres, like all eminent artists who have faith in the endurance of truly beautiful things, M. Meyerbeer hastens slowly. He rightly believes that one always acts quickly enough when one acts well, and the opera Le Prophète is a new testimony to this powerful tenacity that now makes M. Meyerbeer the worthiest representative of dramatic music in Europe.”

Likewise, Edmond Viel (Ménestrel, 29 April) declared: “The cliché, the filler, and the commonplace, those precious resources of mediocre minds, are abhorred by the illustrious master. In his work, every note proceeds from a purpose, and must produce an effect. The pursuit of truthful expression is a constant guiding light. He has never displayed greater mastery in harmonic explorations and orchestral innovations, never been more prolific in lofty inspirations, and more abundant in effortlessly charming melodies. Perhaps he has never more triumphantly tackled the dual challenge of infusing charm into grandeur and maintaining variety within unity.”

Concluding a series of articles on the score a year later, Georges Kastner9 said Le Prophète was characterised by the brilliance, precision, grandeur, and originality of ideas; the firmness of style, vigour of colour, the richness of expressive means; and, above all, the strength and truth of dramatic expression. “Rhythm and melody, harmony and instrumentation, all converge under Meyerbeer’s pen to achieve this ultimate result. Guiding his brilliant imagination according to the laws of a strict poetics, the composer of Le Prophète adheres to an exact portrayal of characters and situations. While delighting the ear, he knows how to speak to the mind and heart.

“What he desires is that the music of the drama resides entirely within the drama, and that the composer’s inspiration fits seamlessly into the mould prepared by the poet without awkwardly spilling over. In short, what he aims for is to remain faithful to the character and fulfil all the requirements of the genre being addressed. The truth of dramatic expression, I repeat, is the constant goal that Meyerbeer has set for himself, worthy in this, as in all things, to rival Gluck, his illustrious predecessor, whose immortal sceptre has passed into his hands.”

But Meyerbeer was disappointed with the opera performed in 1849. “What a difference, when an opera comes from the head and when one sees it in the theatre,” he told his secretary, Johannes Weber, two days before the opening night.10 “He was of course referring to the obtained result, and he had no reason to be entirely satisfied, his Prophète not being as he had conceived it, as a result of the mutilations he had to undertake in the course of rehearsals,” Weber wrote. “Le Prophète as he had understood it was not the one he saw on the stage.”

Scribe had suggested Le Prophète to Meyerbeer in 1836; the composer had completed the first draft in 1841, but lodged the score with his Paris lawyer and refused to stage it because the Opéra director, Leon Pillet, wanted his mistress Rosine Stoltz to sing the role of Fidès, mother of the Prophet, while Meyerbeer wanted Pauline Viardot-Garcia, sister of the bel canto star Maria Malibran. In 1849, Pillet was sacked, and Edmond Duponchel and Nestor Roqueplan were eager to produce Meyerbeer’s opera; the composer agreed to have the work, first conceived 13 years before, staged.

But the tenor selected to sing Jean, Gustave-Hippolyte Roger of the Opéra-Comique, was inadequate to meet the demands of the rôle, so the vocal line was revised, and some of his music removed. In all, an hour of music was cut, and the part of Jean significantly reduced.

“Meyerbeer wanted to make a great Prophet, energetic, convinced of his divine mission, and whom the crowd believes to have come to earth without having been born of a woman,” Weber noted. “In the end, all he got at the theatre was an amiable and friendly Prophet. ‘What a difference!’ he exclaimed, with good reason.”

One has not heard Le Prophète properly until one has heard the uncut version. It is an enormous opera; in its full form, as Meyerbeer envisaged it, it runs for 4 hours and 17 minutes, without intervals – almost as long as Götterdämmerung. (Even in its abridged form, it was one of the longest pre-Wagnerian operas, comprising 25 separate numbers.)

For their scenario, Scribe and Meyerbeer drew on Voltaire’s Essai sur les mœurs et l’esprit des nations. In the 1520s and 1530s, Voltaire wrote, “the Anabaptists devastated Germany in the name of God. Fanaticism had not yet produced such fury in the world; all these peasants, who believed themselves Prophets and knew nothing of Scripture except that it was necessary to massacre mercilessly the enemies of the Lord…” The sect was founded by two “fanatics”, Stork and Muncer; believing themselves divinely inspired, they sought to reform Catholicism and Lutheranism, and killed anyone who opposed them. “They stirred up the peasants against the princes and the aristocracy, telling them that all men were born equal, and that if the popes treated the princes like subjects, the lords treated the peasants like beasts. To be truthful, the manifesto of these savages, in the name of those who cultivate the land, would have been signed by [the Spartan lawgiver] Lycurgus. They asked that only tithes of grains be imposed upon them; that a portion be used for the relief of the poor; that they be allowed hunting and fishing for sustenance; that air and water be free; that their labours be moderated; that they be provided with wood for heating. They claimed the rights of humanity; but they asserted them like ferocious beasts.”

Johan Beukelszoon, or John of Leiden, was the most notorious of the Anabaptist leaders. Claiming that God had named him king of a New Jerusalem, he was crowned in a magnificent and pompous ceremony, and, both monarch and Prophet, he sent out 12 apostles to proclaim his reign throughout Germany. He established a proto-communist regime, in which all property was held in common, particularly by him; and instituted polygamy, forcing unmarried women to marry the first man who proposed to her. He himself married 16 wives, one of whom he murdered for speaking against him; “John of Leiden cut off her head in front of the other wives, who, whether out of fear or fanaticism, danced with him around the bloody corpse of their companion.” According to Voltaire, this tyrant had one virtue: courage. He defended the city of Munster against its bishop, Francis Von Waldeck, for an entire year. At last, betrayed by his own side, he was captured, then tortured with red-hot pincers and executed.

John of Leyden became one of the most striking figures in all opera – a model for such complex, conflicted characters as Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. He is at once a dreamy idealist and mother’s boy, a puppet of the murderously hypocritical Anabaptists, and a ruthless soldier. For Robert Letellier11, Jean is an ambiguous figure, “an enigma and perhaps something of a schizophrenic”, both man of faith and fraudulent impostor. In Jean, the Anabaptists believe that they have found the figurehead they need: he is the likeness of a painting of King David adored in Westphalia; brave and devout, he knows the Bible by heart. When he has served their purpose, they will dispose of him. “Popular idol! … Son of heaven! … Invented to serve our designs, and which, after our success, our hands will overthrow!” exclaims one of the Anabaptists in Act III.12

Jean loses his identity, and falls under the influence of the Anabaptists, becoming the Prophet, but losing his loved ones. He abandons his mother, Fidès, then denies her publicly. Indeed, Berthe, whose abduction spurs him onto terrorism and revenge, is horrified to learn that the Prophet, the man she seeks to kill, and Jean, the man she loves, are one and the same; unable to reconcile her loathing and her love, she kills herself. Jean is brought to repentance by his mother, and rebels against those who made him a revolutionary, destroying both the feudal system (Oberthal) and his seducers (the Anabaptists), and expiating his crimes.

For Letellier, Jean and Fidès’s fiery death shows the repudiation of “ideological passion, greed for power … and the corruption of ideals and values”; like Brünnhilde’s Immolation and the destruction of Valhalla, “human love, this time filial-maternal, and even more fundamental than romantic commitment, proclaims a purified humanity over religion, politics and power”13. Segalini14 also compares Jean to Siegfried, and suggests that the rôle is the model for Heldentenor parts; certainly, Jean is in many ways a Wagnerian hero. In the year of Le Prophète, Wagner took part in the Dresden uprising, and was an admirer of the anarchist revolutionary Bakunin. Wagner was a utopianist who envisaged a new world rising from the ashes of this one, a new world that could only be achieved by the destruction of the existing world order, a new world of liberty and universal brotherhood. Jean is an idealist who commits crimes – war, murder, sacrilege, the violation of human relations, tyranny, injustice – to create that new world.

Le Prophète also introduced a new character to opera: the mother. Fidès is the model for Verdi’s Azucena (Il Trovatore) and Ponchielli’s Cieca (La Gioconda), among others. So important was she that one wag even called Meyerbeer’s opera The Mother of the Prophet! For Kastner15, she was one of the most genuine and well-drawn characters seen on the stage: “Proud and passionate as a mother, humble and chaste as a Christian, this beautiful female figure offers a type that remains true to both the laws of nature and to the customs of sixteenth-century society. Driven by a singular sentiment, wherein all the interest of her life is invested, Fidès, in pursuit of the son she loves, navigates straight toward her goal, unfazed by obstacles. The myriad anxieties of maternal love – its tumults and desires – wash over her poor heart like waves on the shore. She prays, exhorts, blames, encourages, curses, and forgives! The unwavering determination of this sublime will and the escalating energy of this sacred affection elevate and sustain the narrative to great heights. They yield the most potent and moving situations, truly novel and admirable scenes where Fidès’s noble character fully emerges with vividness, grandeur, and poetic resonance. Maternal love is undeniably the principal element in Scribe’s drama, and any trace of another love is but a fleeting imprint – a chaste thread of the Virgin lost in the air on a sombre autumn day.” She may have been based on Meyerbeer’s own mother; Scudo16 felt that the character could only have been created “with intimate memories and personally cherished emotions gathered piously from the depths of the heart”.

Le Prophète combines Italianate bel canto singing, characterised by expressive and lyrical vocal lines, with advanced German orchestration and harmony, while his instrumentation showcases his mastery of orchestral colour and dramatic effect. His music, Adolphe Adam17 wrote, stood out for its grand and elevated quality, making it perfectly suited to capture the most passionate and tumultuous emotions. The historical and dramatic elements influenced Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, particularly in the crowd scenes.

The opera begins with an overture of great power, depicting what Letellier18 identifies as the pastoral, religious, and military themes of the work; it draws on themes from the Act I revolt, Act III’s Anabaptist choruses, Jean’s prayer at the end of Act III, and the coronation march in Act IV. But the overture was not performed, because it was thought too symphonic.

Instead, Act I opened with a few bars of turbulent violins, pizzicato strings, and two mournful clarinets (one in the orchestra pit, the other in the wings) – an andantino pastorale passage that paints a picture of dawn in the Dutch countryside. Mme Castellan, the soprano who created the rôle of Berthe, demanded an entrance aria, even though they were considered old-fashioned and inappropriate for this work. Meyerbeer reluctantly wrote two versions; the first, “Voici l’heure où sans alarmes” (andantino quasi allegretto), is simper, but Castellan preferred the flashier “Mon cœur s’élance et palpite” (allegro brillante). Meyerbeer refused to publish the aria as part of the score. The most effective number in the act is the aforementioned Prêche anabaptiste, a sermon (choral in unison and octave) that leads to a rebellion.

“It sends shivers down the spine,” Berlioz19 wrote. “One senses that the most fearsome of fanaticisms, religious fanaticism, is at play.” In a subsequent review20, he remarked that this grand chorale in the Lutheran style was so authentic “that every time the three Anabaptist crows come to caw, one feels seized by a fury mixed with contempt for these ignoble fanatics, and one searches around for a cannon to mow them down”. Adam21 was also impressed: “There’s a whole revolution in this transformation of the plainchant ‘Venite ad nos, populi’; one can understand that with these simple words, Germany is about to be flooded with blood.” In a lighter vein, Fidès and Berthe’s pretty duet “Un jour dans les flots de la Meuse” (andantino grazioso), in which the two women plead with the Comte to let his vassal Berthe marry Jean. Oberthal refuses, and instead arrests them. The Act I finale is brief, and Oberthal’s line sounds more suited to an opéra comique than grand opéra, but Meyerbeer did not intend this as a proper finale. Acts I and II were performed as a whole; the scene ends with the effective tableau of the Anabaptists standing on the castle stairs, blessing the peasants, who kneel before them, and directing menacing gazes at the castle.

Jean does not appear until Act II, set in his inn in Leiden. While there are some famous numbers, this scene is much more intense when seen, rather than merely heard; it contains strong situations: Berthe’s flight, Jean’s choice between his mother and his fiancée, and the Anabaptists urging Jean to lead their troops (and come over to the dark side). Jean’s dream narrative, “Sous les vastes arceaux”, is very advanced, even proto-Wagnerian; modelled on a speech in Pushkin’s Boris Godunov, it anticipates an event yet to come, and the orchestra (flutes in the lower register, a cornet under the stage, muffled violins) plays ghostly versions of themes that will be heard in Act IV. In Berlioz’s opinion22, it was a “colossal page of orchestration, modulations, and dramatic truth”.

Jean’s pastorale, “Pour Berthe moi je soupire”, refusing the Anabaptists’ Satanic offer of the kingdoms of the world, is used as a theme of reminiscence in Act III.

Fidès’s famous arioso, “Ah! mon fils”, blessing her son for saving her life at the cost of his love, is, as Berlioz said, true and touching.

The act ends with a quartet in which the Anabaptists persuade Jean to follow them and leave his mother, whom he must never see again; it contains a fine phrase, “Adieu, ma mère et ma chaumière”, while the theme of Fidès’s arioso is brought back in the orchestra as Jean hesitates, unsure whether to depart.

Act III takes place sometime later, in the Anabaptists’ camp by night; Jean, the Prophet, has led the Anabaptists to bloody victories throughout the Netherlands and Germany. Meyerbeer and Scribe are not shy about showing that violence; after an entr’acte to march rhythm, featuring the drumbeats and fanfares heard in the overture, the act begins with a bloodthirsty allegro feroce chorus, “Du sang!” The mob drags their prisoners – richly dressed people, eight barons and noblewomen, a monk, children – onstage, and threatens them with axes. Zacharie’s couplets “Aussi nombreux que les étoiles”, rejoicing in the defeat of the Anabaptists’ enemies, a bass battle hymn modelled on Handel, is vigorous and striking.

The third act of grand opéra always featured a divertissement; for Le Prophète, Meyerbeer composed one of the most famous: the Skating Ballet. A chorus of peasants selling food sets the scene; then there are a waltz, a pas de redowa, a quadrille, and a galop – all lively, tuneful, and picturesque. As night falls, the skaters, torches in hand, depart.

The scene changes to the interior of Zacharie’s tent. Oberthal has entered the camp in disguise; unrecognised, he swears an oath, promising to follow the Anabaptists’ creed: respect the peasantry, burn down abbeys and convents, hang the nobility from the nearest oak tree, and seize their wealth. “Moreover, good Christian, my brother, you shall always live holily!” The spectacle of three hypocrites singing a song of murder to a jolly tune, part of it a drinking song, is almost an early example of Brechtian alienation. “Far from being a diversion, this piece, with its biting irony and boisterous humour, lays bare the ugliness at the heart of religious practice and social status,” Letellier23 comments. In a lovely andantino section, a tinderbox is struck, and the Anabaptists recognise Oberthal.

The act’s finale is a grandiose tenor aria, accompanied by chorus. Jean’s army, furious after a failed attempt to capture Münster, revolts; he quells the mutiny, forcing them to their knees in prayer, like a preacher; then leads his followers in a triumphal hymn, “Roi du Ciel et des anges”. The sun rises, to shine on Münster and its ramparts, which Jean points out to his followers; the soldiers shout with joy, and lowers their banners before him. This was the first use of an electric arc light in the theatre – an effect that impressed Meyerbeer’s audience. “The effect of the sunrise is one of the newest and most beautiful things ever seen in the theatre,” Adolphe Adam24 exclaimed. “We witnessed a real sun that couldn’t be looked at directly without being dazzled, and its light reached even the back of the boxes furthest from the stage.” Wagner, however, complained that the mechanically produced sunrise overshadowed the poetic elements of the scene, and reduced the essence of art to mere external effects.

The last two acts are set in Münster, which the Anabaptists have captured and made their stronghold. Instead of liberating Germany, as he declared at the outset of his mission, Jean has become its oppressor. At the start of Act IV, we see the cowed populace in one of the city’s public squares, harried by the soldiers, but forced to declare their loyalty for the Prophet and his army. Fidès has come to Münster; believing her son is dead, murdered by the Prophet, she begs for alms for a mass for his soul. Her Complainte, “Donnez, donnez, pour une pauvre âme”, is plaintive and despairing. Berthe, too, disguised as a pilgrim, has come to Münster. The two women’s duet, “Pour garder à ton fils”, was criticised for being a concession to the singers; Berlioz complained that such vocal virtuosity was unsuited to two peasant women – but the duet is both dramatic and tuneful. There is an exquisite melody in G flat when Berthe thinks she will see Jean again; the two women lament Jean’s death (“Que faire encore sur cette terre”, in E); and the duet ends in an exalted allegro (“Dieu me guidera”) as Berthe vows revenge on the Prophet.

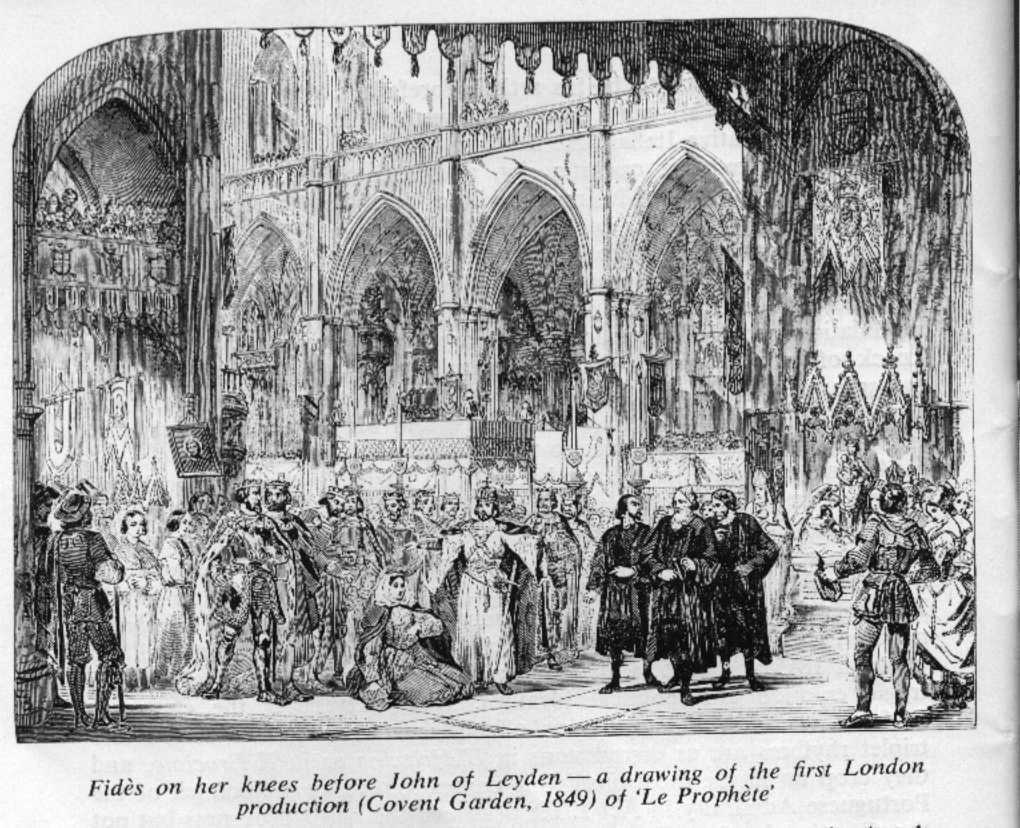

Now comes the magnificent Cathedral Scene. Jean is to be crowned as emperor of Germany; Fidès prays for God’s vengeance on the Prophet, who murdered her son – and is appalled to recognise that the Prophet is her own son. To save her life, Jean declares that she is a mad stranger and performs a sham healing.

It begins with the famous Coronation March (which, incidentally, “influenced” the theme tune for the Australian ABC news for decades). But the familiar version only starts more than 20 bars into the full piece; it is far more impressive in its uncut version, more German and less gaudy.

The Anabaptists (three basses and a tenor) sing a beautiful, solemn quartet, “Domine salvum fac regem nos”; Fidès kneels in prayer, and curses the Prophet. Children, joined by a general chorus, praise the Prophet; it rises to a magnificent climax when Jean enters under a canopy, and is anointed with holy oil and crowned. While the people prostrate themselves, Jean recalls the prediction of Act II: “Jean, you will reign! Ah! So it is true, I am the Chosen One, the son of God!” (The suggestion that the Prophet is neither conceived by, nor born of, woman suggests the Protestant Reformation’s rejection of the female principle. See, for instance, Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation.)

Fidès rises, looks at the Prophet, and cries out: “My son!” Jean wishes to run to his mother, but the Anabaptists threaten to kill her. Controlling his feelings, Jean coldly asks: “Who is this woman?” Fidès, weeping, expresses her indignation in a series of couplets that develop into a fine ensemble, the chorus expressing their confusion, and the Anabaptists their fury. As they are about to stab her, Jean intercedes; he declares that this woman is mad, but a miracle could restore her wits. Fidès sinks to her knees before Jean; he orders the crowd to stab him if he has lied to them; as several Anabaptists place the points of their daggers to his chest, he demands: “Am I your son?” “No,” Fidès at last replies; “I have no son, alas!” It is a psychological masterstroke.

Adolphe Adam25 summed up the views of many: “From the first note to the last, everything is beautiful, admirable, filled with colour and effect, and exudes a character of grandeur, religious majesty, and dramatic power.” For Georges Kastner26, the scene was of historic importance, “marking the degree of perfection that art has already achieved, while also indicating the path that it will henceforth follow”. Few tragedies, he thought, contained such a moving, pathetic, and original plot twist than the one resulting from the recognition of Fidès and her son, and not many musical compositions contained an ensemble piece conceived on such vast proportions, with more skill, depth, order, and clarity, despite the richness of developments and extreme complexity of details. Verdi was deeply impressed; when he came to write grand opéra himself (Les vêpres siciliennes and Don Carlos), he demanded something similar.

From the grandiose cathedral scene, with its pomp and ceremony, Act V moves to the very intimate: a solo, a duet, and a trio. A dark transfiguration of the ‘Ad nos’ theme sets the scene, prefiguring the ominous mutation of the Question motif in Act II of Lohengrin. Fidès is being held prisoner in a vaulted cellar. Her scene, “Ô prêtres de Baal”, is a celebrated mezzo / contralto scene: in a tender cavatina (“O toi qui m’abandonnes”), the mother vows to give her life for her son’s dreams of glory; but, worried that he might have sent his agents to kill her, she is overcome by wrath, and calls on God to illuminate his soul (“Comme un éclair précipité”). Berlioz27 , however, thought the bravura style was inappropriate for an old woman worn out by age and sorrow.

When Jean arrives, Fidès, embodiment of heaven’s wrath, rebukes him, and chastises him for his blasphemy and tyranny; just as he made her kneel before the Prophète in the cathedral, now she makes Jean kneel in repentance. At last, Jean resolves to give up his soldiers and his infamous power. The Grand Duo (“Mais toi, mais toi qu’on déteste”) is good, but rather Donizettish; Meyerbeer’s music was so advanced for its time that one tends to associate him more with Berlioz, Wagner, or even Mussorgsky than with bel canto composers.

Now Berthe comes to this well-frequented cellar; the daughter of a former guardian of the palace, she will lay charges to blow up the Prophet and his palace. Reunited, the peasants sing a trio, “Parlez bas!”; in the allegretto pastorale section, “Loin de la ville”, they express their longing for a peaceful life. Several critics thought it was too pretty for the situation, but it is rather lovely. However, that dream is illusory; Berthe discovers that Jean is the Prophet. This discovery is the final straw, after so much suffering, and she goes mad; her vocal line (“O spectre épouvantable”) becomes erratic, and she stabs herself. In the critical edition, a very bluesy saxophone accompanies her death scene; Meyerbeer’s grand opéra suddenly turns into film noir.

Jean resolves to bring down all those who have ruined him. The opera ends at a lavish banquet: Jean toasts his followers in an ironic drinking song (“Versez! que tout respire”), then blows them all sky-high.

Meyerbeer and Scribe’s view of revolutions is a cynical one – but Meyerbeer would not have been surprised when Napoleon III imposed an authoritarian rule. Nor would he have been surprised by the Communist régimes of the twentieth century, nor by Hitler’s charismatic enthralment of the German people, nor by today’s strongmen and would-be dictators. Le Prophète is Prophetic.

Recordings

Recordings

Listen to: Nicolai Gedda (Jean de Leyde), Marilyn Horne (Fidès), Margherita Rinaldi (Berthe), and Robert El Hage (Zacharie), conducted by Henry Lewis, Turin, 1970.

Watch: John Osborne (Jean de Leyde), Kate Aldrich (Fidès), Sofia Fomina (Berthe), Mikeldi Axtalandabaso (Jonas), Thomas Dear (Mathison), Dimitry Ivaschenko (Zacharie), and Leonardo Estevez (le Comte d’Oberthal), conducted by Claus Peter Fior, Toulouse, 2017. (Here’s my original review.)

- Robert Ignatius Letellier (ed.), The Diaries of Giacomo Meyerbeer, Volume 2: 1840-1849: The Prussian Years and Le Prophète, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2001, entry for 23 February. ↩︎

- Edmond Viel, Le Ménestrel, 22 April 1849. ↩︎

- Henri Blaze de Bury, Meyerbeer et son temps, Paris: Michel Lévy frères, 1865, pp. 150-51. ↩︎

- Quoted in Robert Ignatius Letellier, The Operas of Giacomo Meyerbeer, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2006, p. 209. ↩︎

- Fétis père, Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, 22 April 1849. ↩︎

- Quoted in Letellier, Operas, p. 197. ↩︎

- Quoted in Letellier, Operas, p. 296. ↩︎

- Paul Scudo, « Le Prophète de M. Meyerbeer », Revue des Deux Mondes, 22 April 1849. ↩︎

- Georges Kastner, Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, 14 April 1850. ↩︎

- Quoted in Matthias Brzoska (ed.), Le Prophète: Critical Edition, Ricordi. ↩︎

- Robert Ignatius Letellier, “The Nexus of Religion, Power, Politics, and Love”, in Meyerbeer Studies: A Series of Lectures, Essays, and Articles on the Life and Work of Giacomo Meyerbeer, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2005, p. 82. ↩︎

- Zacharie: « Idole Populaire! … Fils du ciel ! … Inventé pour servir nos desseins, et qu’après le succès renverseront nos mains ! » ↩︎

- Letellier, “Nexus”, p. 85. ↩︎

- Sergio Segalini, Diable ou prophète ?: Meyerbeer, Paris: Éditions Beba, 1985, p. 77. ↩︎

- Kastner, Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, 10 February 1850. ↩︎

- Scudo, op. cit. ↩︎

- Adolphe Adam, Le Constitutionnel, 18 April 1849. ↩︎

- Letellier, Operas, p. 194. ↩︎

- Hector Berlioz, Journal des Débats, 20 April 1849. ↩︎

- Hector Berlioz, Journal des Débats, 27 October 1849. ↩︎

- Adam, Constitutionnel, op. cit. ↩︎

- Berlioz, Journal des Débats, 27 October 1849. ↩︎

- Letellier, Operas, p. 196. ↩︎

- Adam, Constitutionnel, op. cit. ↩︎

- Adam, Constitutionnel, op. cit. ↩︎

- Kastner, Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, 7 April 1850. ↩︎

- Berlioz, Journal des Débats, 20 April 1849. ↩︎

This was such a delightful read, and I’m glad you agree that is is one of the greatest operas ever written. I honestly cannot think of another opera with such a smart and complex libretto. Scribe has been accused of many things, but his genius really shines here. I am not ashamed to admit I prefer all of Meyerbeer’s last six operas to anything Wagner wrote. Mainly, despite being really long, they hold my attention to the end. They are all about relatable human beings and human concerns, with none of the dull metaphysical point-making that seems to have plagued opera since Wagner. I have no idea why Operas like Tristan, Parsifal, Pelleas and Melisande, even Nixon in China keep getting performed over and over while Meyerbeer is largely ignored. I know things seem to be turning around, albeit slowly, which is encouraging.

You prompted me to re-listen to the Horne set (she is perfect in this role). I have yet to hear the complete mashup on youtube, or the new set — which is only a few minutes longer than the Horne, so I wonder if it’s worth having?

What really struck me is that you count among your greatest half-dozen Benvenuto Cellini. I have never seen or heard it. Perhaps I should. I saw Les Troyens in Los Angeles (the entire 5-hour shebang, as it were), which was eye-opening. I also love Damnation, which SHOULD be staged as an opera. The Nelson recording of Cellini seems to be the preferred one.

Anyway, I should not complain about Wagner so much, as Meistersinger really is a great opera and, I should add, the only Wagner that doesn’t put me to sleep at some point in the proceedings.

LikeLike

Thanks, Gregory! I’ve loved Le Prophète since I heard it 17 years ago – although I have a slight preference for Les Huguenots. Meyerbeer’s musical and Scribe’s dramatic imagination create something extraordinary. Both have terrific libretti; memorable characters; and great melodies. Grand opéra (particularly those of Scribe and Meyerbeer) worked on the level of both “serious commentary on politics / society” AND exciting melodrama.

Which Wagner couldn’t do; his operas might be philosophical, but they’re dreadfully static and untheatrical. (Do people really go to the theatre to watch Wotan argue with his wife or his daughter for an hour?) Still, as you point out, things are changing; audiences are throwing off the shackles of Wagnerian high-mindedness, and enjoying opera once again. (If the directors will let them!)

You haven’t heard Benvenuto Celllini? Oh, you must! It’s bursting at the seams with vitality; it’s a kind of grand opéra-comique, humorous in parts, serious and spectacular in others; Berlioz himself thought he had never had such a wealth of musical ideas (including a 20-minute finale). It should have been a hit, but it was too advanced, even for audiences who had heard Les Huguenots (which was slightly ahead of the public). Try both Davis (with Gedda) and Nelson.

LikeLike

Since I wrote this comment I have purchased and listened to the Nelson recording and have fallen head over heels. Absolutely magnificent score, from beginning to end, and and it sounds really difficult to play and sing. I’m not surprised this is done so infrequently. I can’t tell how it would work on stage, so I should probably check out a video. It’s really top-drawer Berlioz, and to my ears it sounds better than Trojans (which has some dry spots).

LikeLike

This is quite an impressive review! I don’t see a link to your book (?)

It’s an interesting fact that his crowd scenes influenced Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov.

Why did Meyerbeer take so long between Huguenots and this opera? What did he do in the meantime?

LikeLike

Meyerbeer composed Le Prophète circa 1840, then revised it eight years later. He was also Prussian Generalmusikdirektor and director of music for the Royal Court, and composed an opera for Germany.

My books aren’t on Meyerbeer, but they are co-written with Robert Letellier, the Meyerbeer expert.

LikeLike