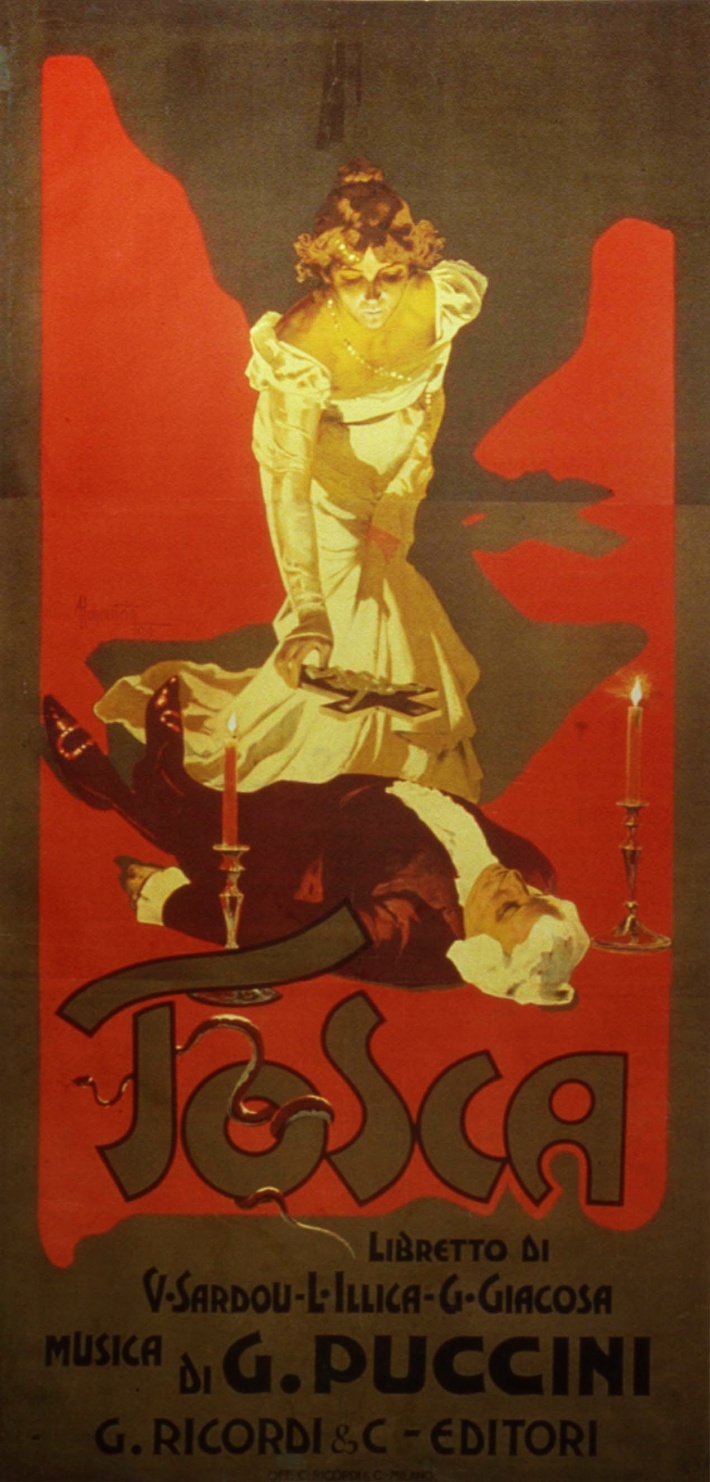

- Melodrama in 3 acts

- By Giacomo Puccini

- Libretto: Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, after Victorien Sardou’s play La Tosca (1887)

- First performed: Teatro Costanzi, Rome, 14 January 1900

| Floria TOSCA, famous opera singer | Soprano | Ericlea Darclée |

| Mario CAVARADOSSI, painter | Tenor | Emilio De Marchi |

| Il Barone SCARPIA, Head of the Police | Baritone | Eugenio Giraldoni |

| Cesare ANGELOTTI | Bass | Enrico Galli |

| The Sacristan | Baritone | Ettore Borelli |

| SPOLETTA, police agent | Tenor | Enrico Giordani |

| SCIARONNE, gendarme | Bass | Giuseppe Gironi |

| A Jailer | Bass | Aristide Parasassi |

| A Shepherd | Boy | Angelo Righi |

| A Cardinal – The Judge – Roberti, executioner – A Scribe – An Official – A Sergeant Soldiers, altar boys, noblemen and women, townsfolk, etc. |

SETTING: Rome; June 1800.

Tosca is one of a half-dozen operas that everyone knows: the one where an opera singer (performed by an opera singer) performs “Vissi d’arte”, and knifes an over-enthusiastic admirer.

It’s one of the most popular examples of verismo opera, which focuses on realistic (often working class) characters and situations, violently intense emotions, and just plain violence.

Tosca has all of those: torture, attempted rape, murder, death by firing squad, and suicide. But it’s a sophisticated work, and one with plenty of heart and great melodies.

The opera opens with a series of ominous, fortississimo chords associated with Baron Scarpia, Rome’s corrupt chief of police. Scarpia lusts after the opera singer Floria Tosca, whose boyfriend Mario Cavaradossi is a revolutionary. When Cavaradossi helps a political fugitive to flee, Scarpia arrests him and offers Tosca a bargain: save Cavaradossi’s life at the cost of her virtue. Cavaradossi, though, must appear to die; he will face a firing squad, but the guns will be loaded with blanks. Scarpia, though, has no intention of keeping his word; Cavaradossi is a rival, and must die. Tosca accepts the odious bargain – and then stabs Scarpia to death.

The heroine is one of the great roles in all opera: a passionate, sensitive soul who lives only for art and for love, but who becomes a murderess.

Who is Floria? What is she? A spitfire? A sophisticated woman of the world? An innocent in a political world? Headstrong, or vulnerable and uncertain? Like all great roles, a talented actress can find new dimensions. I say “actress”; the part calls for a soprano who can both sing and act, rather than planting herself at the front of the stage and delivering to the footlights.

Maria Callas was, many believe, the definitive Tosca.

In this 1964 Covent Garden production, her performance is mercurial, always in motion, balanced by Tito Gobbi’s portrayal of Scarpia as an ironic, laughing sadist – a man so in command he can remain suave and gentlemanly even while torturing and blackmailing his victims. We see the moment when Tosca contemplates killing Scarpia; she lowers the wineglass to the table with almost glacial slowness. She is ferocious in the murder, as implacable as Clytemnestra stabbing Agamemnon. Even her forgiveness of the dead Scarpia sounds as inexorable as a hanging judge’s pronouncement. The Greek soprano is a Eumenide. Then she is desperate to flee from the scene of the crime – but she cannot. She acts under compulsion, sobbing as she places the candles by the corpse, and kisses the crucifix that she lays on Scarpia’s breast. She veers about the stage, looking for an escape, for a clue to her guilt, for anything left behind – and then the music calls her to her senses. The drums sound, and she rushes from the stage, leaving the door open in her haste.

Shirley Verrett, in the Met’s 1978 production (online here), plays a more vulnerable Tosca. She steels herself when Scarpia approaches her, and looks nauseated by his touch. She spots the knife; the thought of murder enters her head; she recoils from both the knife and the idea, drinks wine to give herself courage… The deed done, she is terrified by her act. She almost flings the crucifix onto Scarpia, and stumbles blindly out.

The part of Tosca may call for a singing actress, but Puccini also uses the metatheatricality of the role for dramatic effect. Tosca is an opera singer, a star of the stage – and reality and theatre blend around her. Scarpia mockingly applauds her performance while she begs him not to torture Cavaradossi: “Tosca on the stage was never more tragic!” She retells the murder as an encore performance for Cavaradossi. We see how she would play it as an actress, but this also sanitises the crime; she distances herself from the deed while she turns the messy details of the murder into drama. She gives directions to Cavaradossi how to play the death scene, and applauds his “acting” when he’s shot. And here Puccini does something very clever.

Tosca thinks, until the very end, that she will get a happy ending. Remember: the opera is set in 1800; this was the time of the rescue opera, in which villains may capture a husband or wife, but which invariably ended with tyrants defeated and lovers reunited. (The most famous today is Beethoven’s Fidelio.) She knows how this should go, based on her stage experience. She hasn’t realised she’s in an Italian verismo opera circa 1900.

In the long, agonisingly long, execution scene, Puccini uses the difference between what she expects to happen and what is happening, to ratchet up the tension until strained nerves start to scream.

“How long is this waiting!” Tosca says. “Why are they still delaying? The sun already rises. Why are they still delaying? It’s only a comedy, I know, but this anguish seems to last for ever!”

She praises Cavaradossi’s performance – “There! Die! Ah, what an actor!” – and is radiantly happy until she turns over Cavaradossi, and realises that she’s been rejoicing at her lover’s death.

The action may be tragic, but, as William Berger (Puccini Without Tears, 2005) [1] suggests, works on several levels. It’s simultaneously a gripping melodrama and an allegory about the triumph of love and liberty over cruelty and tyranny.

[1] Berger sees the opera as a conflict between the Apollonian and the Dionysian, building on Nietzsche, possibly via Peter Conrad. It’s a brilliantly illuminating essay.

The opera pits revolutionaries (Cavaradossi and his friend Angelotti) against the despotism of Scarpia and the Bourbons, who ruled Rome at the time. Napoleon, advancing on Rome, is seen as a redeemer, a bringer of liberty. [2] When he hears of Napoleon’s victory at Marengo, Cavaradossi, who has just been tortured by Scarpia’s men, rises threateningly towards Scarpia and sings: “The avenging dawn now rises to make the wicked tremble! And liberty returns, scourge of tyrants!” When he learns she killed Scarpia, he calls Tosca an avenging angel, justice inspired by love. Their final duet (as in Verdi’s Aida) is a sort of anthem, imagining the triumph, the apotheosis of love. They may not enjoy that happiness here on Earth, but their souls will enjoy it in heaven.

[2] This is partly the French source (Sardou’s play). Illica also wrote the libretto for Franchetti’s Germania, where Napoleon is a despot.

IAGO’S FAN

Scarpia, in Act I, compares himself to Iago:

| Per ridurre un geloso allo sbaraglio

Jago ebbe un fazzoletto, ed io un ventaglio! | Iago had a handkerchief, and I a fan

to drive a jealous lover to distraction! |

Italian operagoers would have taken the reference to mean the character in Verdi’s Otello, not to Shakespeare’s villain. Scarpia is, like Jago, a manipulator who lies to trap a couple and who turns another’s jealousy to his own ends.

On another level, it’s a statement of artistic purpose. Puccini is declaring himself Verdi’s heir. Verdi himself had heard Illica read his libretto to Sardou; more, he had, according to legend, “seized the manuscript from the librettist’s hand and read the passage [Cavaradossi’s farewell to life] in a voice trembling with emotion” (Charles Osborne, The Complete Operas of Puccini, 1983).

Just as La Bohème is descended from La traviata (Parisian setting, heroine who leaves boyfriend for what she thinks is his own good and who dies of consumption), here Puccini is using the complex, villainous Verdi baritone who’s the enemy of the couple in love. He’s implicitly saying that he is the modern composer carrying on the Italian tradition, using Verdi’s tropes, set to modern, through-composed, post-Wagnerian music.

SUGGESTED RECORDINGS

Watch: The 1976 film starring Raina Kabaivanska (Tosca), Plácido Domingo (Cavaradossi) and Sherill Milnes (Scarpia), with the Ambrosian Singers and New Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Bruno Bartoletti. The film, directed by Gianfranco de Bosio, was shot on site in Rome.

The 1978 Met Opera production starring Shirley Verrett (Tosca), Luciano Pavarotti (Cavaradossi) and Cornell MacNeil (Scarpia), conducted by James Conlon. Directed by Tito Gobbi.

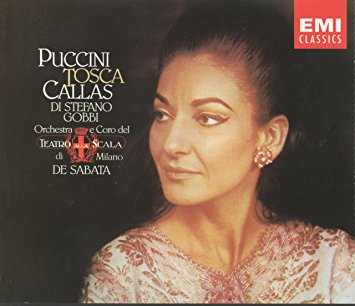

Listen to: The 1953 EMI recording starring Maria Callas (Tosca), Giuseppe Di Stefano (Cavaradossi) and Tito Gobbi (Scarpia), conducted by Victor de Sabata.

I have so many mixed feelings about this piece. The music is sooo beautiful, but I find the first act so boring. The second is better, but only after the torture scene starts. Still, the sound is truly remarkable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, my feelings are a bit mixed, too. I think it’s more theatrically effective than Butterfly, but the music isn’t as good. (And Butterfly’s characterisation is better, and it’s a more moving work.) Tosca’s music is quite through-composed; the only highpoints, I think, are Scarpia’s “Te deum” in Act I, “Vissi d’arte” and the revolution song in Act II, and “È lucevan le stelle” in Act III.

LikeLike

Perhaps for its theatricality, I also enjoy the end, from ‘com’è lunga l’attesa’ onwards. I particularly love the ending on the de Sabata recording and not only for Callas. I just _adore_ the way Angelo Mercuriali screams his lungs out condemning Tosca. I hate when any tenor just sing this small part. But Mercuriali gives the best way to end the opera. You’re right, it’s a melodrama that we just want to know the end of it?

LikeLike