GUSTAVE III, OU LE BAL MASQUÉ

- Opéra historique in 5 acts

- Composer: Daniel-François-Esprit Auber

- Libretto: Eugène Scribe

- First performed: Théâtre de l’Opéra (salle Le Peletier), 27 February 1833, conducted by F.A. Habeneck

| GUSTAVE III, King of Sweden | Tenor | Adolphe Nourrit |

| ANKASTROM, his friend | Bass | Nicolas-Prosper Levasseur |

| AMÉLIE, Countess of Ankastrom, in love with Gustave | Soprano | Cornélie Falcon |

| OSCAR, the King’s page | Soprano | Julie Dorus-Gras |

| ARVEDSON, fortune-teller | Mezzo | Louise-Zulmé Dabadie-Leroux |

| DEHORN, conspirator | Bass | Henri-Bernard Dabadie |

| WARTING, conspirator | Tenor | Alexis Dupont |

| A Chamberlain | Tenor | Hyacinthe Trévaux |

| ARMFELT, Minister of Justice | Bass | Ferdinand Prévost |

| GÉNERAL KAULBART, Minister of War | Bass | Pierre François Wartel |

| CHRISTIAN | Tenor | Jean-Étienne-Auguste Massol |

| A Servant of Ankarstrom | François-Alphonse Hens | |

| ROSLIN, painter | Silent | Ferdinand |

| SERGELL, sculptor | Silent | Henri |

SETTING: Stockholm, 15th and 16th March 1792

Gustav III, King of Sweden (r. 1771-1792), was an enlightened despot and lover of the arts, murdered in 1792 by a conspiracy of nobles.

In many ways, Gustav was an attractive figure. He was an enthusiast for Enlightenment ideals, particularly French writers like Voltaire. He promoted free trade; encouraged religious tolerance, and, to a limited extent, press freedom; improved health care; restricted the death penalty; and abolished torture to extract confessions.

He was the first head of state to recognise the States, when the Americans were fighting their War of Independence.

He also founded the Swedish Academy, built the Royal Swedish Opera and Ballet, and wrote historical dramas and opera libretti.

The nobles, though, had good reason to hate the king. He had curtailed their power, ended traditional privileges, allowed ordinary citizens to enter government, and waged an unpopular and unsuccessful war with Russia.

And so, on the night of 16 March 1792, Captain Jacob Johan Anckarström, a military officer, shot Gustav at a masked ball at the Royal Opera House on 16 March 1792.

The king survived, but the wound became infected. Gustav died of scepticaemia a fortnight later.

According to operatic lore, though, Gustav’s murder was personal.

Anckarström was Gustav’s best friend, and Gustav was in love with Anckarström’s wife Amelia.

That’s why Anckarström shot him.

Today, the story is best known for Verdi‘s brilliant treatment, Un ballo in maschera (1859). But Verdi based his opera on Auber’s work of a quarter of a century before.

Auber (1782-1871) is little known today, but was once one of the most popular composers in Europe. Tom Kaufman, for one, considered him one of the three giants of French opera in the mid-19th century, alongside Meyerbeer and Halévy.

While I wouldn’t put Auber quite in the top rank, his operas are delightful entertainment. The music is “light”, but it’s always clear, tuneful, charming, and never less than pleasing.

Perhaps that’s why Rossini called the diminutive composer Piccolo musico, ma grande musicista (“a small musician, but a great maker of music”).

Wagner, no less, was a big fan.

“His music – at once elegant and popular, effortless and precise, graceful and robust, and letting its whimsy take it where it would – had all the necessary qualities to capture and dominate the public’s taste. He seized song with a witty vivacity, multiplied rhythms to infinity, and gave ensembles a characteristic zest and freshness almost unknown before him.”

And the young Richard raved about La muette de Portici (1828), a historical epic about the Neapolitan fisherman Masaniello’s revolt against Habsburg Spain in 1647:

It is a national work of the sort that each nation has only one of at the most… This tempestuous energy, this ocean of emotions and passion, depicted most vividly and shot through with the most individual melodies, compounded of grace and power, charm and heroism – is not all this the true incarnation of the French nation’s recent history? Could this astonishing work of art have been created by any composer other than a Frenchman? – It cannot be put any other way – with this work the modern French school reached its highest point, winning with it mastery over the whole civilised world.

(Yes, even when talking about opera, Wagner thinks in terms of total world domination.)

Such a vivid operatic subject was a complete novelty – the first real drama in five acts with all the attributes of a genuine tragedy, down to the actual tragic ending… Each of these five acts presented a drastic picture of the greatest vivacity, in which arias and duets in the conventional operatic sense were scarcely to be detected any more, or at least – with the exception of the prima donna’s aria in the first act – no longer had this effect. Now it was the entire act, as a larger ensemble, that gripped one and carried one away.

That opera was revolutionary in more ways than one. It inspired Wagner’s music dramas – and was the spark for the creation of Belgium.

Auber’s opéras comiques – many written in collaboration with top librettist Eugène Scribe (after whom, of course, this blog is named) – influenced Gilbert & Sullivan, Offenbach, and Viennese opera.

They include:

- Fra Diavolo (1830), about a romantic Italian bandit

- Le cheval de bronze (1835), a fantastical tale set in ancient China and on the planet Venus (before scientists discovered the planet is 462 °C, and has an atmosphere of poisonous carbon dioxide gas and sulphuric acid)

- Le domino noir (1837), in which a young Spaniard falls in love with a nun

Only nine of his nearly 50 operas have been performed in recent decades. Les diamants de la couronne (1841), Haydée (1847), and Manon Lescaut (1856) have also been produced at Compiègne. La sirène (1844) was performed in early 2018, but is not yet available on CD. After the warmly received Domino noir in Paris this year, hopefully more will follow.

And the overtures are exhilarating.

The best book in English on the composer is Robert Letellier’s Daniel-François-Esprit Auber: The Man and His Music (2010).

Gustave III has one of Scribe’s cleverest, tightest plots, full of surprises and reversals, and one of Auber’s richest scores. It was Auber’s second grand opera, five years after the sensational success of La muette de Portici.

The first opera codified the genre: a serious, spectacular historical work in five acts, often making a (liberal) social or political point.

Gustave is an advance on La muette, Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable (1831),or Rossini’s Guillaume Tell (1829). It’s a more intimate, naturalistic drama, where the protagonists’ private lives matter more than politics. The gifted, capricious Gustave; Amélie, torn between love and duty; and the jealous, betrayed Ankarström feel like individuals in a way that, say, the princesses Elvire, Mathilde, and Isabelle, or the tenor roles Arnold and Alphonse don’t.

Scribe’s next major libretti, La juive (1835, for Halévy) and Les Huguenots (1836, for Meyerbeer), would boast more complex, conflicted characters, while later grand operas (e.g. Guido et Ginevra, 1838, for Halévy; La favorite, for Donizetti, 1840; or La reine de Chypre, for Halévy, 1841 – the latter two are not by Scribe) are intimate affairs, ancestors of Gounod‘s drame lyrique.

The opera is a tragedy set to the tune of a dance. The theme of the brilliant Act V galop whirls through the five acts, a leitmotiv that symbolises the gaiety, hedonism, and irresponsibility of the king, and the masked ball where he will die.

Gustave has three excellent arias: two show his feelings for Amélie (Acts I and V), while the couplets “Vieille sybille” is a great tune, a definite earworm! Amélie’s Act III aria calls for stratospheric high notes (high E). The couple’s Act III love duet has a beautiful phrase “O tourment…” in the andantino.

The finales and ensembles are ingenious. The Act II finale is great fun; and the Act III finale has a chorus of mocking laughter (an effect used by Verdi). There are two excellent trios (II and III), while the quintet (IV) is one of Auber’s masterstrokes. Five different emotions treated simultaneously with great skill and elegance: three men conspire to murder the King, Amélie worries about her husband and her lover, and the page Oscar looks forward to the pleasures of the ball.

The dance music is exhilarating – and members of the public took to the stage to join in the festivities. The preludes to Act II and III (with its tolling bell) show an unexpected ability to create a menacing, almost Beethovenian, atmosphere.

Performed 168 times in Paris, with lavish stage sets and costumes, Gustave III was well received, but seldom produced after 1840. (Auber, always modest, thought the blame lay with him. He wrote the score between December 1832 and February 1833, while the opera was being rehearsed.)

Act V, with its famous ballet, was, like Act II of Guillaume Tell, often staged on its own. The work fared better internationally, and was a regular part of the repertoire in German-speaking countries, staged as late as the 1870s.

The Italians admired it, and ransacked it for their own operas. “Magnificent, spectacular, historical!” enthused Bellini, who saw it in Paris. “The situations are fine, really fine and new.” Had he lived, his treatment would have been his next project after I puritani.

One Vincenzo Gabussi wrote Clemenza di Valois (1841); both he and his opera are completely forgotten.

Later, two talented Italian operatic composers would use Gustave III as the basis for their works. Mercadante‘s Reggente costs hundreds of dollars on CD, and there’s no English or French translation, although a video is online.

For modern audiences, the elephant in the room is Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera, whose libretto is essentially a translation of Scribe’s into Italian.

Ballo is probably Verdi’s most brilliant opera, dancing nimbly between tragedy and comedy, with a giddily inventive score.

Opera, in this case, works on Darwinian lines; there seems to have been only room for one treatment of the story of Gustav III, and, in an instance of natural selection, Un ballo in maschera has made Auber’s opera extinct.

Critics don’t help. While Vincent Giroud (French Opera: A Short History, 2010) considers the work “one of Scribe and Auber’s finest achievements”, and Herbert Schneider (in The Cambridge Companion to Grand Opera, 2003) writes largely positively about the work, others are less kind.

Ardent Verdians like Julian Budden and Charles Osborne, writing when Italian opera was still considered slightly unrespectable, run down Auber’s opera (and French opera, as a whole) to elevate Ballo.

Budden (The Operas of Verdi, Vol. 2, rev. 1992), for instance, writes: “The musical pillars of the new establishment were Auber, Meyerbeer, and Halévy, at whose hands grand opera achieved a complexity and scale undreamed of before. Schumann and Mendelssohn might sneer; yet, so long as one does not mistake Meyerbeer and his colleagues for great composers (and many Frenchmen at the time did so mistake them), there is no harm in admitting that Parisian grand opera was a stimulating influence all over Europe, and that it played an important part in the genesis of Wagnerian music-drama…”

He dismisses Gustave as “a rather uninteresting museum piece, though one from which Verdi did not scorn to learn”. The libretto – “a cleverly constructed plot in which irony follows irony” – is “ideal work for a theatre that put more value on sensation than on truthful portrayal of character” – but Auber’s “music is mostly trivial, even-paced and dull, with just a progression here or a melodic turn there to remind us that Auber’s is a genuine personality”.

Osborne (The Complete Operas of Verdi, 1969) calls Gustave “a neat, well-constructed melodrama which bore absolutely no relation to the life and times of Gustavus III”. The king becomes a “cardboard cut-out”. He says little about Auber’s music. He likewise calls Les Huguenots “a piece of cardboard theatre and gargantuan proportions”, musically negligible apart from a phrase in the fourth act; suggests that Scribe turned out scripts and libretti in his sleep; and implies that Meyerbeer churned out “prolix … and emptily professional” opera after opera.

No, Gustave isn’t Ballo, but it’s still a wonderful opera in its own right.

SYNOPSIS

Libretto (in French) here

ACT I

The King’s palace in Stockholm – A vast, rich waiting room

While Gustave III rehearses his opera Gustaf Wasa, conspirators led by Count Adolph Ribbing and Claes Fredrik Dehorn plot to murder him. The king has worries of his own; he loves Amélie, married to Ankaström – an offence to honour and friendship.

Gustave organises war with the Russians, and a masked ball which the most beautiful women in court (including Amélie Ankaström) will attend.

Ankaström tells Gustave that he knows why he is unhappy – but the king is relieved when it’s only a warning of a conspiracy, not love for his friend’s wife.

Gustave learns that the fortuneteller Mme Arvedson is under threat of exile – and decides to investigate for himself, in disguise.

ACT II

The fortune-teller’s house

Gustave, disguised as a sailor, arrives first at Mme Arvedson’s. He’s amused to watch the fortuneteller wow the crowd by conjuring up Beelzebub.

Amélie arrives; she confesses she loves an important person at court, and struggles not to love him. Mme Arvedson tells her to go at midnight, and pluck a herb from the executioner’s field. Gustave will secretly follow her there.

The courtiers arrive. The king, still incognito, asks Mme Arvedson to tell the sailor’s fortune.

It’s not a happy fortune: he will die, murdered by the person who first shakes his hand – Ankaström, arriving late. When the king reveals himself, all make fun of Mme Arvedson, who warns them that the dark powers will not be lightly mocked. The conspirators plan to kill the king, but are prevented by the arrival of the people.

ACT III

The executioner’s field on the outskirts of Stockholm

Midnight. Amélie arrives, frightened but determined, to get the magic herb. The vision of the king rises up before her, though.

So does the real king. He declares his love. She begs for mercy, but is tempted by her feelings. She struggles to regain her senses…

and hears at that moment someone approaching: her husband Ankaström! He has come to warn the king that the conspirators have followed Gustave here, and plan to murder him. Gustave entrusts the veiled woman to Ankaström’s care; he will guide her to the outskirts of Stockholm, without speaking to her. The king escapes.

The murderers arrive, and confront Ankaström. Seeing armed men threaten her husband, Amélie forgets everything. She cries out to them to spare his life, and throws herself between them. The veil falls from her face – and everyone recognises her. Ankaström, thinking he understands all, arranges to meet Ribbing and De Horn the next morning – and plot Gustave’s assassination.

(Someone’s also done the Act III finale with emoticons, which is cute!)

ACT IV

Ankaström’s house

Ankaström threatens to kill Amélie to punish her adultery. She pleads her innocence, and Ankaström spares her life; he will kill Gustave instead. De Horn and Ribbing arrive, and Ankaström joins their conspiracy. He is chosen by lot to kill the king. Oscar comes to invite the Ankaströms to a masked ball at the Opera that evening – for the conspirators, a perfect opportunity for murder.

ACT V

First tableau: A gallery in the palace, connected to the Opera

Alone, Gustave resolves to send Amélie away. He will name Ankaström governor of Finland, and the couple will leave the next day.

Second tableau: The ballroom of the Opera

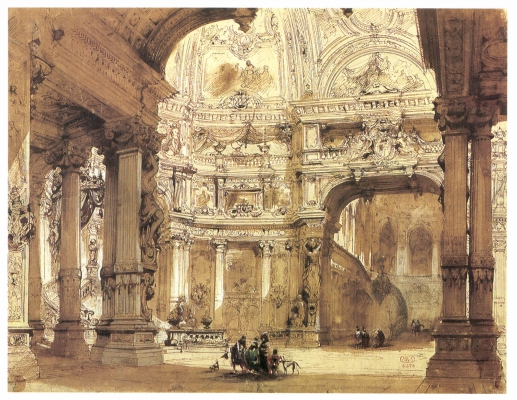

The ball scene was one of the highlights of the Paris production, with 300 people onstage, 100 taking part in the galop alone.

Jules Janin described the scene thus:

I believe that never, even at the Opéra, was seen a spectacle more grand, more rich, more curious, more magnificent, that the fifth act of Gustave. It is a fairlyland of beautiful women, of gauze, of velvet, of grotesqueness, of elegance, of good taste and of bad taste, of details, of learned researches, of esprit, of madness and of whimsicality — of every thing in a word, which is suggestive of the eighteenth century. When the beautiful curtain is raised, you find yourself in an immense ballroom.

The stage of the Grand Opéra, the largest in Paris, is admirably adapted for masked balls, and the side-scenes being removed, the stage was surrounded a salon, the decorations of which corresponded with those of the boxes.

This salle de bal is overlooked by boxes, these boxes are filled with masks, who play the part of spectators. At their feet, constantly moving, is the circling crowd, disguised in every imaginable costume, and dominoes of every conceivable hue. Harlequins of all fashions, clowns, peddlers, what shall I say? One presents the appearance of a tub, another of a guitar; his neighbor is disguised en botte d’asperges; that one is a mirror, this a fish; there is a bird, here is a time-piece — you can hardly imagine the infinite confusion. Peasants, marquises, princes, monks, I know not what, mingle in one rainbow-hued crowd. It is impossible to describe this endless madness, this whirl, this bizarrerie, on which the rays of two thousand wax tapers, in their crustal lustres, pour an inundation of mellow light. I, who am so well accustomed to spectacles like this — I, who am, unfortunately, not easily disposed to be surprised — I am yet dazzled with this radiant scene.

At the height of the festivities, tragedy strikes. Amélie warns Gustave that his life is in danger – and Ankaström shoots him. The dying king pardons them all.

SUGGESTED RECORDING

Laurence Dale (Gustave), Rima Tawil (Amélie), Christian Tréguier (Ankaström), Brigitte Lafon (Oscar), Valérie Marestin (Arvedson), Gilles Dubernet (Dehorn), and Roger Pujol (Ribbing), with the Ensemble Vocal Intermezzo and : Orchestre Lyrique Français, conducted by Michel Swierczewski. Compiègne, 1989.

Divertissements: Philippe Taglioni; sets: Léon Feuchère (Act I, Act V tableau 2), Jules Dieterle (Act II), Alfred (Act III), Charles Cicéri (Act IV), René Philastre & Charles Cambon (Act V tableau 1). Costumes: Eugène Lami & Paul Lormier.

Wow, was I stumped. Not really, I’ve had this on my short list for about a year and just never got around to it. I had hoped you were doing Verdi’s Ballo but only because it is one of my 5 favourite Verdi operas. Auber’s treatment (I heard the first ten minutes months ago) really isn’t bad although it is rather amusing to see that Verdi’s opera is a condensed grand opera in miniature. I’d like to do this and Muette soon but who knows. I’m currently working on a revision for Les Huguenots.

You really worked on the historical background here. I’m a little surprised that this ended up being one of your longest posts.

LikeLike

Well, French grand opera is a specialty of mine! Ballo will be next. I watched the Met production with Pavarotti this week, but had to listen to Gustave before I could write up Verdi.

What are the other four favourite Verdis? My tops would be Ballo, Aida, Otello, Don Carlos – all obvious choices! I once knew a bloke whose favorite Verdi was Attila.

Revising Huguenots?

LikeLike

Basically the same as yours although Traviata has a special place in my heart (family reasons). I’m not as enraptured by Aida although I recognize its musical enjoyabilty. In total honesty I like all Verdi except I masnadieri (to me it is his worst, period) and Giovanna d’Arco, although of the more famous ones I’m not too keen on Trovatore or Vepres. I like Il Cosaro although I know it isn’t remotely one of his best, and I prefer Jerusalem to Lombardi. I like Attila, but I would probably place it around number 11th or 12th. I prefer it to Forza though. Otello and Don Carlos are his very best, although which one is better than the other I haven’t a clue. I also think I’m one of the few people who “gets” Falstaff.

I think listening to Auber first was probably rather wise in light of Verdi’s later work.

As for Huguenots, I’m tackling one of those 4 hour recordings to replace my review of the 1963 Sutherland/Corelli recording. Good heavens no one could ever improve upon the score of Huguenots!

LikeLike

I really don’t know Traviata. (A gap!)

I find Verdi very uneven. The mature operas are (nearly!) all wonderful, in different ways, but the galley ones aren’t very interesting. (I fell asleep during Nabucco!) They feel crude compared to Donizetti – less conventional, but also less polished. (Plus bipolar heroes, gloom and doom, and often preposterous plots!)

I probably wouldn’t place him in my top half-dozen opera composers (who? – Meyerbeer obviously, Massenet, Berlioz, Rossini, Offenbach, maybe Gluck, maybe the great Russian composer Glinsky-Mussodin. Can I count G&S?)

I put up the Brussels Huguenots a year or so back: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDfpOu-VWGw This has previously unheard material for the first three acts – including a new aria for Marcel, and an extended Act III finale.

Now for the first half of Ballo!

LikeLike

Really, you’ve never seen Traviata? It is the most performed opera on the planet right now by a rather wide margin, even I’ve seen it live. It would be fifth on my top five though, it is TOO popular really but I suppose high class prostitutes with TB are in vogue right now. Musically I find it extremely tuneful which is why I like it so much. Considering that you are a music critic I’m a little surprised you’ve never had to see it for work. I don’t know I love Verdi (with rare exceptions), to each his own I suppose. Ironically I always find Donizetti crude (possible exception of Roberto Devereux, but I’m also weird because I hate Donizetti’s comic operas, especially Don Pasquale, don’t get me started, I want to smack everyone in the cast), but I will admit that the plots of most early Verdi operas are rather stupid although I love the oratorio-nature of Nabucco. There is shockingly marked improvement starting with Macbeth though Masnadieri is to me a big let down. Stiffelio would be just outside of my top five. I really do not believe that Alzira is his worst opera, maybe fourth or fifth from the bottom, but it isn’t the worst. Masnad has a dreadful plot (based on Schiller no less) and is musically uninspired with a meaningless soprano role. Giovanna d’Arco has a train wreck for a libretto and sedate choral numbers, although at least Verdi got some inspiration out of the character of Joan. I like Luisa Miller a great deal more than you do though, although it takes a full half hour to warm up. I prefer Jerusalem to I Lombardi because the latter is an episodic wreck with needless walk on characters (only four characters appear in more than 3 out of the opera’s 11 scenes, madness!). The act 3 violin concerto is obviously filler (the opera is barely 2 hours), although not bad. The revision also massively benefits from a French musical intervention. Those are two I would love to see you do, a comparison of Jerusalem and I Lombardi! I trash the latter too much so don’t base your judgement on me.

Yes, Glinka, Mussorgsky, Borodin, and Tchaikovsky were all very interesting as opera composers. G&S are sort of opera, more properly operetta though. Forman would probably say that if Lakme can be considered an opera so could G&S.

I await Ballo then! Take your time, no hurry.

LikeLike

Journalist who’s written freelance music articles, properly speaking!

Never seen Traviata live. I’ve watched the Domingo/Stratas film and heard the Kleiber recording with Cotrubas – but that was years ago!

LikeLike

Okay, that makes me feel a little better. I just would have found it odd if you had never heard Traviata before.

LikeLike

Perhaps it’s also its ubiquity. Opera Australia here does Traviata / Carmen / Bohème / Tosca / Butterfly every year or two. When something “rare” – Simon Boccanegra, Don Carlos, or Otello – appears, it’s cause for rejoicing!

LikeLike

Otello is rare? Really? I guess it is rather difficult to cast properly. I do get tired of the standards though, hence my blog being about far-out operas like the latest one I did. What do you think of Mayerling? As for Sidney, will they revive Les Huguenots any time soon?

LikeLike

I was being sardonic; Opera Australia tends to do a lot of warhorses. The big Verdis, Puccinis, Mozarts. Still, we got Don Quichotte this year.

Huguenots? Good grief, no!

LikeLike

Ballo is up!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By the way, do you know where I can lay hands on an English or French translation of Gomes’ Guarany libretto? My CD (Sony!) only has a synopsis.

LikeLike

Try this link:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044044229227;view=1up;seq=5

Apparently Harvard/DPLA has an English translation side-by-side with the original Italian. I’m surprised it isn’t on Google Books or Internet Archive.

LikeLike

Awesome! Thanks, man!

LikeLike

Sure, I’m guessing you are investigating that Italian-hybrid genre the opera-ballo? Well, if I did Maria Tudor a few months ago….

LikeLike

No; the luck of the draw!

LikeLike